- Home

- News & Features

- News

- FY2019

- TOWARD TICAD 7: ‘Africa & Me’ Part 7 — Junko Nakazawa, JICA expert: The ‘School for All’ project has spread to 45,000 schools; “I hope to expand schools that community members, parents, and teachers support together all throughout Africa.”

News

July 25, 2019

TOWARD TICAD 7: ‘Africa & Me’ Part 7 — Junko Nakazawa, JICA expert: The ‘School for All’ project has spread to 45,000 schools; “I hope to expand schools that community members, parents, and teachers support together all throughout Africa.”

"I believe education is vital for the development of countries and regions." The person passionately speaking these words is JICA expert Junko Nakazawa, who has been involved in the ‘School for All’ project for many years, primarily in West Africa.

Junko Nakazawa explains the importance of transparency in financial management to the people of the community at the general community meeting held at the ‘School for All’ pilot school. (Location: Ghana)

Junko Nakazawa explains the importance of transparency in financial management to the people of the community at the general community meeting held at the ‘School for All’ pilot school. (Location: Ghana)

The ‘School for All’ project is an education project started by JICA in 2004 in which education is led not by the state or local government but rather by people from local communities, as well as parents as main actors, who are actively involved in supporting children's education. The management of the schools is conducted in a democratic and transparent manner with the cooperation of school principals and teachers. In this seventh installment of the series “TOWARD TICAD 7: ‘Africa & Me’”, we ask Junko Nakazawa about her memorable episodes about the ‘School for All’ project.

My encounter with Africa began with questions from my childhood

Nigerien mothers use locally available soil to create blocks for classroom construction. Literally, they plan the work of building the schools on their own and implement it through a school action plan.

Nigerien mothers use locally available soil to create blocks for classroom construction. Literally, they plan the work of building the schools on their own and implement it through a school action plan.

"There are parents who want to be involved in supporting the education of their children even though they themselves did not have school experience, and there are people who are interested in supporting education even if they do not have children at school. For example, there are people in the local community who want to repair the classroom using their woodworking skills. Everyone in the community can participate and support school activities in various ways, that is the ‘School for All’ project.”

Nakazawa describes the project and continues as she looks back on how she first began to take an interest in developing countries.

"When I was a child, I heard from Bangladeshi people who worked near my parents' home that ‘Bangladesh is a beautiful country, and people living there are cheerful and warm.’ However, I also saw on a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadors TV program that Bangladeshi is ‘a poor country, and there are many pitiful people there.’ I felt a strange gap between what I heard from the people and the TV report. Eventually, my eyes began to turn to overseas, especially to developing countries.”

After studying International Education and Development at graduate school, she joined JICA's Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers in her late twenties. She experienced a full-blown encounter with Africa while working as a community development officer in Tanzania. She was involved in supporting the activities of youth and women's groups for 2 years.

"I did realize there were so many things I could not learn just sitting at a desk. I learned much more from local people than I taught them as a community development worker. When I didn’t know right from left, they warmly smiled and provided me advice. I was captivated by the ‘depth of the bosom’ of African people, and I wanted to become closely involved with them.”

After that, Nakazawa worked as an associate expert at JICA headquarters and was assigned as a long-term expert to Niger in 2006, and began working for the ‘School for All’ project.

During her approximate 3 and half years of activities in Niger, where the gender gap was fairly intense, she was particularly impressed by the campaign to increase the school enrollment rate of girls. "The school enrollment rate greatly improved, but the most important contribution at this time was an awareness creation activity organized bymothers of the community. In some countries, women’s decision-making power is limited in their household. However, in the project target area, there are many cases where fathers migrate to other countries to work, leaving mothers alone with children at home. Therefore, mothers become the main decision-makers and get closely involved in the education of their children. Each country or culture has a variety of backgrounds, and I learned that, for enlightenment and support, a ’supple gaze’ is essential.

In Ghana, I discovered even more possibilities of expansion for the ’School for All’

A general community meeting is held in the ‘School for All’ pilot project. This scene shows teachers, parents, and local residents discussing school issues. (Location: Ghana)

A general community meeting is held in the ‘School for All’ pilot project. This scene shows teachers, parents, and local residents discussing school issues. (Location: Ghana)

Nakazawa took advantage of her experiences in the French-speaking African region when she was transferred to Ghana in February 2015. She attempted to introduce the ‘School for All’ program in the English-speaking African region for the first time. Working with the Ministry of Education in Ghana, she started with 23 pilot schools in 2 districts and eventually numbers expanded to 50 schools.

"There were indications that English-speaking countries had their unique culture and system and that the conventional model of the French-speaking countries may not work. However, there was a common sense among parents that they wish to provide better education for learning to their children, if at all possible. The curiosity of children is also strong, regardless of the country, so my colleagues in the field and I were convinced that there were potential needs.”

Yet, it was not easy. Therefore, Nakazawa took the government officers of the Ministry of Education in Ghana on a study tour to Senegal and other countries where ‘School for All’ project had already kicked off. She strongly persevered to explain the effectiveness of democratic school management, and that took about two years. "In the end, the people in charge were overwhelmed, and the pilot was accepted.”

Even in Ghana though, which is referred to as a ‘middle-income developing country,’ some areas far from urban regions have a high degree of poverty, and the level of education among adults is lower than those in other areas.

"At one time, I learned that a reticent youth facilitator (a local volunteer education support staff), who dropped out of junior high school himself, was making home visits to a child who was absent from his remedial classes and was working hand-in-hand with him. What is important is not the education level of the facilitator, but rather their passion to contribute to the development of children for their future! It was an event that reminded me once again of their enthusiasm, and I reflect on that experience often and use it to progress towards the future. "

Thus, the ‘School for All’ pilot project was successful in Ghana, and by the end of 2018, throughout Africa, the ‘School for All’ model was successfully introduced into approximately 45,000 schools.

Nakazawa, who left Ghana in February 2019 and returned to Japan, said, “I would like to continue to be involved in supporting education in Africa in some way. In particular, I would like to present a gender-free math and science education role model, especially for women, known as ‘Rikejo’ in Japan. I think this can eradicate the image that ‘only boys are good in math and science.’ Ultimately, I hope that I can support African women to bring out their potential through education." The ‘School for All’ project is still evolving, and her eyes sparkle with the potential she sees in it to produce various possibilities.

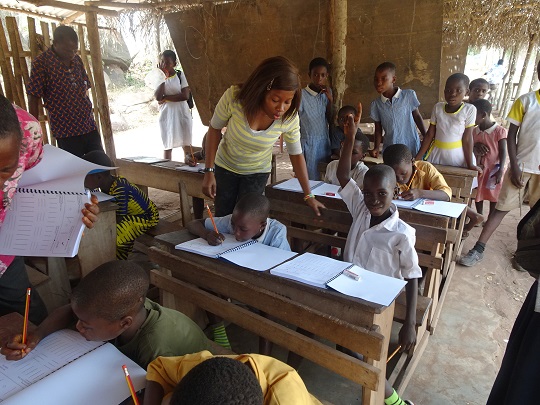

In the ‘School for All’ pilot project, a remedial class was held by the initiative of the community. JICA-developed math drills are used as teaching materials. (Location: Ghana)

In the ‘School for All’ pilot project, a remedial class was held by the initiative of the community. JICA-developed math drills are used as teaching materials. (Location: Ghana)

PROFILE

Junko Nakazawa

As a JICA long-term expert, she has been supporting education in Africa for nearly 14 years. Her main life work is related to ‘education’ and ‘gender’ activities. She completed a master's degree in ‘International Education Development and Gender’ at a graduate school in England. Currently, she is a senior consultant at Asuka World Consultants Co., Ltd. She was born in Tokyo.

Related Link

- About JICA

- News & Features

- Countries & Regions

- Our Work

- Thematic Issues

- Types of Assistance

- Partnerships with Other Development Partners

- Climate Change / Environmental and Social Considerations

- Evaluations

- Compliance and Anti-corruption

- Science and Technology Cooperation on Global Issues

- Research

- JICA Development Studies Program / JICA Chair

- Support for the Acceptance of Foreign HRs / Multicultural and Inclusive Community

- Publications

- Investor Relations