- Home

- News & Features

- News

- FY2019

- The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics is awarded to development economists: How JICA utilizes their evidence and methodologies

News

December 6, 2019

The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics is awarded to development economists: How JICA utilizes their evidence and methodologies

The 2019 Nobel Prize for Economics was awarded to Professor Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee and Professor Ester Duflo, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Professor Michael Robert Kremer of Harvard University. Professor Banerjee and his colleagues won the award because they conducted innovative research based on field experiments to verify the effectiveness of policies towards alleviating poverty in developing countries.

Utilizing this field experiment, JICA is making efforts to improve its education development projects such as “School for All,” aiming at improving children's learning in developing countries.

On the occasion of this award, we asked Eiji Kozuka, Director for Basic Education Team II of the Human Development Department and Senior Research Fellow of JICA Research Institute, what JICA is doing in this field and what results have been achieved.

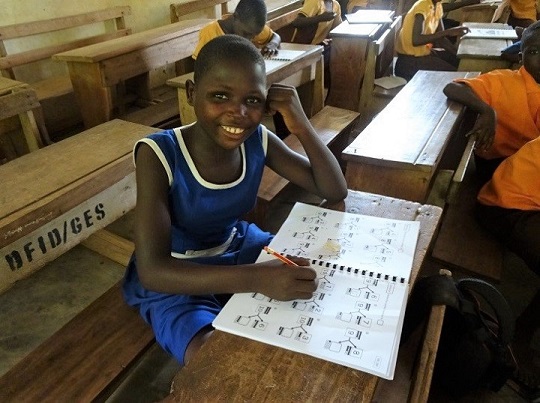

Children solving math drills at an elementary school in Ghana where the education development project "School for All" is being implemented

Children solving math drills at an elementary school in Ghana where the education development project "School for All" is being implemented

What kind of research is this “Field Experiment for Global Poverty Reduction”?

This field experiment uses a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) (Note 1) to scientifically measure the effectiveness of development policies.

Note 1

RCT is an experiment in which people or units in an evaluation sample are randomly assigned into treatment group and control group, and the treatment group receives an intervention, while the control group does not. After the intervention, the results are compared and examined to understand the effectiveness of the intervention.

Field experiments often show that policies that we believe are “effective” are not always effective. In the field of education, for example, providing grants, textbooks, and teaching materials to schools are popular interventions in developing countries. However, field experiments have shown that providing these inputs alone are not so effective, and an additional intervention, such as teacher training, is necessary for improving student learning.

To ensure that policy is informed by scientific evidence, Professor Banerjee and Professor Duflo founded The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Laboratory (J-PAL) at MIT. J-PAL brings together world-renown development economists, and has had a major impact on real-world development policies.

What field experiments have been implemented under JICA's “School for All” project, and what results has the project achieved?

“School for All” is a community-based project in which communities and schools work together to improve the learning environment for children. The project began in Niger in 2004 and has been implemented at approximately 45,000 schools in seven African countries, including Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Madagascar, and Ghana, as of the end of 2018.

An elementary school in Burkina Faso where a School for All project was being implemented

An elementary school in Burkina Faso where a School for All project was being implemented

When the JICA Research Institute (JICA RI) was established in 2008, a research project started to evaluate the basic model of “School for All” (Note 2), headed by Yasuyuki Sawada, Professor of the University of Tokyo and then Visiting Research Fellow of JICA RI. The research team conducted a field experiment in Burkina Faso, and its result showed that the model not only improved student enrollment and teacher attendance, but also enhanced trust between communities and schools.

Note 2

In the basic model, the community selects the core members of the School Management Committee (SMC) in an election. The committee then plays a central role in facilitating collaboration between the community and the school by organizing community meetings. The meetings are a forum for them to understand and discuss the issues surrounding the school and to implement activities to resolve these issues.

Children preparing school meals at an elementary school in Burkina Faso where a School for All project is being implemented

Children preparing school meals at an elementary school in Burkina Faso where a School for All project is being implemented

In 2012, we began another field experiment in Niger, targeting an extended model of the School for All (Note 3). The model provided school grants to School Management Committees (SMCs), and conducted capacity building training for SMCs to share children's test results with the community and to learn how to improve the quality of education. The result of the experiment shows that grants alone did not improve children's test scores, but the capacity building training contributed to its improvement.

Note 3

The extended model incorporates additional interventions to address local needs such as improving learning and nutrition on top of the basic model.

Are the results of Professor Banerjee and his colleagues' research utilized in the School for All?

In order to improve children's learning, the School for All is also working on “utilization” of the evidence from Professor Banerjee and his colleagues’ previous field experiments. Specifically, in cooperation with the Indian NGO Pratham, the School for All is incorporating the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach into their model.

Unlike the general public school education system, TaRL divides classes according to children’s proficiency levels, not by age or grade. Professor Banerjee and his colleagues collaborated with Pratham to conduct several field experiments, demonstrating that TaRL is highly effective in improving children's literacy.

The School for All experts are working to incorporate this TaRL approach into their model. A trial of 180,000 children at 1,650 schools in Madagascar and 10,000 children at 101 schools in Niger showed that the average test scores for children had risen dramatically. The experts are making continuous efforts to refine the model.

An elementary school in Madagascar where a TaRL class is being held with the School for All model

An elementary school in Madagascar where a TaRL class is being held with the School for All model

Why is the School for All successful in developing countries? I believe an important factor is its approach to strengthening the relationship of trust between schools and communities.

In the international debate on educational development, some claim that the approach for the community to monitor schools is more effective in improving academic performance. This is because in developing countries, many teachers do not show up to work at school, and several studies demonstrate that employing and monitoring teachers under short-term contracts gives teachers incentives to perform better. This approach, however, can create tension between schools and communities and can lead to nationwide opposition from teacher unions.

Parents electing SMC representatives in Senegal

Parents electing SMC representatives in Senegal

On the other hand, the "School for All" emphasizes equal relationship between schools and communities rather than monitoring schools. We need to examine whether the new model with Pratham can further improve children's learning over the medium to long term, but we believe that this approach has great potential.

What should JICA and the international society do, going forward, for educational development by utilizing field experiments?

It is estimated that more than half of the children in the world, and nearly 90% in Africa, have not achieved the minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics, and this is dubbed as the “Learning Crisis.” This is a surprising number, but if one looks at classrooms in developing countries where teachers often do not come, children do not understand teaching language, and textbooks are not delivered to children, one can see that it cannot be easily solved.

Niger children studying in a straw classroom with no electricity, desks or chairs

Niger children studying in a straw classroom with no electricity, desks or chairs

To solve these issues, the international community is calling for the mobilization of financial resources, but without policies to utilize the funds effectively, the money will be wasted. In the field of education, numerous field experiments have been carried out around the world, and evidence is accumulating over the years. Therefore, it is essential for the international community to cooperate in implementing evidence-based policies.

JICA needs to make further efforts to adopt global evidence in an appropriate way to improve the effectiveness of our projects and disseminate it around the world. In the field of basic education, JICA has conducted field experiments not only in the School for All, but also in teacher training in Ethiopia and textbook development in El Salvador.

JICA also hosted seminars jointly with J-PAL and Pratham. On the left, Eiji Kozuka, director for the Human Development Department

JICA also hosted seminars jointly with J-PAL and Pratham. On the left, Eiji Kozuka, director for the Human Development Department

Collaboration with partner institutions is also important to maximize development effectiveness and impact. In June 2018, JICA concluded a Memorandum of Cooperation with J-PAL and Pratham, and in August 2019 with the World Bank, in the field of basic education, and agreed to strengthen cooperation in projects, research, and public events. We, together with developing countries and partners, should accelerate efforts for all the children to overcome the “Learning Crisis.”

- About JICA

- News & Features

- Countries & Regions

- Our Work

- Thematic Issues

- Types of Assistance

- Partnerships with Other Development Partners

- Climate Change / Environmental and Social Considerations

- Evaluations

- Compliance and Anti-corruption

- Science and Technology Cooperation on Global Issues

- Research

- JICA Development Studies Program / JICA Chair

- Support for the Acceptance of Foreign HRs / Multicultural and Inclusive Community

- Publications

- Investor Relations