Daiki Iga

English edited by Desiderio Luna/Olivier Fabre

(Spreading compostable waste on degraded land in Niger/ Photo: Oyama Shuichi)

Series : Africa in Focus

In the lead-up to the 9th Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD9) in August 2025, JICA is sharing a series of stories that explore Africa’s challenges and promise. While showcasing JICA’s contributions, the series also brings attention to the broader efforts, ideas and potential across the continent. This instalment focuses on climate change and disaster risk management.

Africa is often described as a land of hope: a continent rich in energy, talent and untapped potential. From bustling cities to rural communities, opportunities for growth and social development are everywhere. Yet the daily lives of millions are overshadowed by harsher realities: severe environmental degradation, entrenched poverty, hunger, and conflict that can turn optimism into struggle..

For JICA, Africa is not just another region on the map but a crucial partner in this battle. Japanese experts, volunteers and professionals are on the ground, working shoulder to shoulder with local communities and JICA to confront these challenges.

Mozambique: Promoting Marine Debris Cleanup to Become “Africa’s Cleanest Coastal Nation”

For Yasui Takuya, Mozambique proved to be a life-changing destination. He arrived in 2017 as a JICA volunteer, spending two years tackling the country’s pressing waste management challenges. It was there that he met both his future wife, then a JICA staff member, and a friend who would later become his business partner in projects tackling marine debris.

Spanning the southeastern coast of the African continent, Yasui quickly grew fond of Mozambique. Summer temperatures could climb to 35°C, but the heat was far less oppressive than in Japan. Despite the occasional inconveniences, like power outages, the locals were warm and welcoming, and he was pleased to find Japanese ingredients like rice and miso readily available.

After completing his JICA volunteer term, he returned to Japan for a short period. But when his wife was reassigned to Mozambique, he faced a choice. He could have stayed in Japan, but his thoughts kept drifting back to Mozambique, the country he grew to love. In the end, he packed his bags and returned.

Another pivotal moment in Yasui’s journey came at an event at Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD7) in 2019, where he crossed paths with Egawa Yuki, a former JICA volunteer working like himself tackling marine debris. The two immediately connected and agreed to join forces. Their shared passion quickly turned to action, and together they co-found the nonprofit organisation Clean Ocean Ensemble.

(Collecting Marine Debris Using a Retrieval Device / Photo: Yasui Takuya)

According to the OECD’s Global Plastic Outlook 2022, the accumulated amount of marine plastic waste worldwide had reached approximately 30 million tonnes in 2019. Projections by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the World Economic Forum indicate that by 2050, if current trends continue, the weight of plastic in the oceans could surpass that of all fish combined.

Furthermore, collecting marine debris is also crucial for combating climate change. The oceans are often called the “lungs of the Earth” for their role in absorbing greenhouse gases. Clearing marine debris not only allows more sunlight to reach the water, helping seaweed flourish and boosting the oceans’ capacity to capture greenhouse gases. It prevents accidents, such as fishing boat propellers getting entangled, which also contribute to disaster risk reduction.

Clean Ocean Ensemble, guided by its vision of “A World With Zero Marine Debris”, is developing innovative collection devices designed to be affordable and adaptable for use anywhere, promoting both recycling and debris cleanup

The system features a custom-designed net, roughly one metre by thirty metres, deployed on the sea surface to efficiently capture floating debris. A gap between the net and the seabed to allow fish to swim freely, ensuring only debris and seaweed carrying microplastics are collected. Powered by tidal currents, the device requires no electricity, though the team has also experimented with towing the nets using boats.

However, questions remained over whether the device, already trialed in Japan, could be successfully adapted abroad. Board member Yasui was assigned to trial it in Mozambique. The project, which began last April, has faced its share of challenges. Each device costs around 200,000 yen, a heavy cost for local residents. The installation requires sourcing materials such as fishing nets and carefully assembling the device. Explaining its purpose and operation to communities often proved difficult, and results did not always match expectations.

(Yasui Takuya and Local Staff Conducting a Trial in Mozambique/ Photo: Yasui Takuya)

Some challenges arose that would be unheard of in Japan. In Yasui’s home country, the collection devices can remain in the water for two weeks, but in Mozambique, they had to be retrieved each night to prevent theft. Collecting debris from rivers carried another hidden danger: local staff warned that landmines, most likely remnants of the 1977-1992 civil war, still lurked along certain riverbanks.

Getting the project off the ground required careful negotiations with government offices and local fishing authorities. Yasui’s experience as a JICA volunteer proved invaluable; by drawing on his connections, he managed to navigate bureaucracy and launch the initiative. While Portuguese is Mozambique’s official language, he quickly learned that using local greetings in native tongues soften people’s expressions and made them more approachable.

Yasui will leave Mozambique this August when his wife’s assignment comes to an end. The project, which he says he has carried forward with help from many people, from building the devices to collecting debris, will be handed over to a local NGO. Looking ahead Yasui says hopes it will help make Mozambique “the most committed country in addressing the marine debris problems in Africa.”

Niger: A “Magical” Project Tackling Waste and Desertification Simultaneously

At first many thought solving waste problems and desertification at the same time would be an impossible feat. Yet under the leadership of Professor Oyama Shuichi, collected city waste was spread on barren land. Soon, grass began to sprout, enabling livestock to graze and crops to flourish. Witnessing these results, local communities gradually came on board, supporting the project that seemed almost magical.

Professor Oyama of Kyoto University Graduate School, who also leads the Organic Material Circulation Project at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, launched this project in Niger, located in the semi-arid Sahel region south of the Sahara Desert, in 2015. Today, it has expanded to five countries in total, including Djibouti, Uganda, Zambia, and Ghana, with at least one government having considered it for adoption as an official national programme.

(Spreading waste on dry land to transform it into soil suitable for growing plants. The land changes in the timed sequence: top left → top right → bottom left → bottom right/ Photo: Oyama Shuichi )

Questions naturally arise: “Does the waste contain harmful substances? Could the soil be contaminated?” In Niger, much of the waste, metals and PET bottles, is already collected by waste pickers. The remainder is largely sand (50%), fallen leaves and vegetable scraps (30%), cardboard (10%) and plastic (10%). Surprisingly, the plastic wastes actually serve a purpose: it helps retain soil moisture and provides a habitat for termites, which play a key role in greening the land. In other words, the waste can be used as- is.

For three years from September 2021, Oyama received support from JICA’s Grassroots Technical Cooperation Project in Niger. With no Japanese embassy in the country and few Japanese residents, the JICA office was tiny, consisting of only four staff members, including the Resident Representative, all who assisted with networking and logistics.

Starting from scratch, Oyama had no contacts within government agencies. With the guidance of local JICA staff, he managed to organise presentations for officials and even speak at international forums, gradually expanding his network. A breakthrough came when he was introduced to senior officials at the Ministry of Environment, accelerating the project’s progress. Reflecting on the experience, Oyama notes that the government’s support reflected the trust built through the years of JICA’s consistent engagement.

(Professor Oyama and local Staff / Photo: Oyama Shuichi)

JICA has a 60-year history of cooperation with Niger. Its predecessor, the Overseas Technical Cooperation Agency, began providing technical assistance in 1965. Today, JICA continues to work closely with local communities on education, agriculture and rural development, and efforts to maintain peace and stability across the Sahel.

Although Japanese staff typically rotate every two to three years, local personnel often remain on projects much longer. Following the 2023 coup in Niger, the Japanese government issued an evacuation order, forcing Japanese personnel to leave and prompting the JICA office to scale back its operations. Despite these challenges, local staff continue to support the project, a testament to the trust JICA has built in the communities over many years.

“Trust is built over a long period. Japan’s international brand may not yet be fully recognised, but these steady, on-the-ground activities certainly strengthen confidence in Japan,” Oyama said.

He sees the worsening divisions around the world today as rooted in hunger and poverty. On the African continent, desertification is spreading rapidly in the areas bordering the Sahara. Overuse of land accelerates degradation, forcing people to migrate to cities or abroad in search of survival. These migrations can heighten social tensions.

Yet when plants regrow on once-barren land, livestock can graze, and crops can be harvested and sold, livelihoods improve. And this diminishes the need for migration, Oyama says. In Niger, even small disputes, such as one person’s livestock grazing on another’s grass, have escalated into deadly conflicts, claiming many dozens of lives. There has been a case of one person’s livestock eating another’s grass that led to a dispute that claimed around 100 lives. Fertile land, Oyama notes, can prevent such tragedies.

The challenges in Niger also mirror issues Japan faces. While desertification is not a concern in Japan, managing urban waste remains pressing. Oyama hopes a portion of this waste can be recycled in eco-friendly systems, proving that solutions in Africa can offer lessons for Japan as well.

Oyama’s motivation traces back to his childhood, when he learned of desertification in the Sahel. “It was shocking. Even as a child, I wanted to do something about it.” Though his career path did not immediately lead him here, looking back, his connection with Niger feels fated. The third of August - Niger’s Independence Day - also happens to be Oyama’s birthday. For him, this is not just a coincidence; its destiny.

Ethiopia: Bringing Japanese Research Home to Combat Soil Erosion

Birhanu Kebede, a researcher at Bahir Dar University in Ethiopia, spent three years in Japan, from 2017 to 2020, studying soil erosion countermeasures at Tottori University under a scholarship from SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development), a programme supported by JICA and other organisations.

During his time in Japan, Kebede explored and succeeded in proving that soil amendments, such as polyacrylamide (a polymer compound), gypsum, lime, and biochar, could improve water retention in the soil, reduce surface runoff and prevent soil loss.

Ethiopia is one of the countries hardest hit by soil erosion. Heavy rains wash away the nutrient-rich topsoil, making it difficult for crops to thrive. Combined with rapid population growth, this environmental challenge has pushed many young people to abandon farming, moving instead to urban areas or other countries in search of a better life.

(Soil erosion in Ethiopia / Photo: Birhanu Kebede)

Kebede warns that climate change is likely to worsen the problem. Rising temperatures and irregular rainfall patterns are making heavy, unpredictable storms more frequent, while widespread deforestation — driven by demand for wood for fuel and construction — further accelerates soil loss. “In the wake of TICAD9, there will be opportunities to find ways to apply Japanese technologies and expertise to help tackle the growing problem of soil erosion in Africa,” he said.

During his studies in Japan, Kebede was struck by the country’s abundant greenery and hopes that Ethiopia, with its vast stretches of bare land, might achieve a similar landscape. Beyond environment technologies, he also absorbed lessons in Japanese time management, work ethic, and consideration for others. On a lighter note, he developed a particular fondness for Japanese cuisine, especially sushi and karaage (Japanese-style fried chicken).

JICA Focuses on Climate Change, Disaster Risk Reduction, and Agricultural Support in Africa

The Africa continent is widely regarded as one of the regions most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, in part due to fragile social infrastructures. Rising temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns trigger frequent disasters, leading to crop failures, food shortages, poverty, and even social conflicts.

With a population currently estimated at around 1.5 billion - and expected to grow rapidly - the stakes are high. Without improvements in living conditions and disaster preparedness, large-scale migration from rural areas to cities, and from domestic regions to other countries, could intensify social unrest and heighten international tensions.

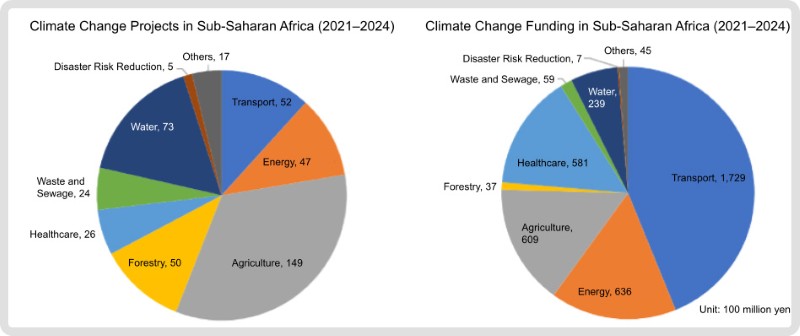

For JICA, supporting climate change measures in Africa is a high priority. Between 2021 and 2024, JICA initiated 443 projects contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation in Sub-Saharan Africa, with total funding reaching 394.2 billion yen (see graph).

The agricultural sector leads in the number of climate adaptation initiatives, aiming to increase food production for 250 million people, improve nutrition for 270,000 people, train 50,000 rice cultivation specialists annually, and boost the average income for one million small-scale farmers by 2030.

Urban populations are also expanding rapidly. To enhance climate resilience, JICA plans to strengthen support for urban adaptation, including infrastructure development, urban master planning, and waste management strategies that account for climate change impacts.

“In Africa, the challenge extends beyond agriculture and urban development to water resources, disaster risk reduction, and other critical areas,” said Usui Yukichi, Director of Team 1, Environmental Management and Climate Change Group at JICA’s Global Environment Department. “Efforts must reduce vulnerability to climate change and limit greenhouse gas emissions over the medium to long term, while promoting sustainable development. Public sector support alone is not enough - private sector participation is essential. For example, Japanese agricultural machinery is highly valued (in Africa) for its durability, and Japanese cars are widely used.”

JICA’s support for Africa goes beyond financial assistance from the Japanese government, relying on expanding public-private partnerships to bring Japanese technologies to the continent - often referred to as the “last frontier,” Usui, who joined JICA as a new graduate in 2002 and spent about a decade stationed in Africa, has witnessed the continent’s challenges and strengths firsthand. Reflecting on TICAD9, he hopes it will foster meaningful global connections and lasting encounters that benefit the future of African continent and Japan.

(JICA support for climate change measures in sub-Saharan Africa, cumulative 2021–2024; units in 100 million yen/ Source: JICA)

scroll