Through the Noto Peninsula Earthquake

2024.04.04

-

- Mochizuki Shota Office for Human Resources for Development Cooperation Human Resources Department

We would like to express our deepest condolences to those who lost their lives in the Noto Peninsula Earthquake of 2024, and our deepest sympathy to all those affected by the disaster.

I worked as a disaster relief volunteer in Noto for approximately two weeks from the end of January 2024. I would like to share what I experienced during my volunteering activities in the disaster areas.

On January 1, 2024, at around 4:10 p.m., an earthquake with a maximum tremor of 7 on the Japanese seismic scale and a magnitude 7.6 on the Richter scale occurred on the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan. The earthquake was larger than the Southern Hyogo earthquake that caused the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Kumamoto earthquake , and a tsunami was observed over a wide area on the Sea of Japan side, causing extensive damage to buildings and roads. In Noto, there are many old wooden houses that have not yet been made earthquake-proof, and the violent shaking caused them to collapse one after another, resulting in a disaster that killed a large percentage of the people who were trapped under the houses.

JICA has been working with local partners in the region as a disaster relief volunteer to maintain and strengthen relationships of trust with local governments and organizations that have worked together with JICA in the past on projects such as acceptance of technical training participants and grassroots technical cooperation programs, and to maintain knowledge, technology, and human resources for solving problems related to international cooperation. Consequently, we have decided to dispatch our staff to the areas. At the time, I was a member of the Secretariat of Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers and was assigned to the Noto Peninsula to replace one person who had already been dispatched there. In cooperation with the Japan Overseas Cooperation Association (JOCA) and the social welfare corporation BUSSI-EN, we supported the operation of evacuation shelters as disaster relief volunteers based in Noto. While assisting as volunteers, we looked into the status of non-Japanese residents and local communities and municipalities affected by the disaster. This is to understand what support should be provided in the future for restoration of any disaster areas.

The drive from Kanazawa to Noto would normally take about two to three hours. However, it took about five hours because the roads leading to the Noto Peninsula were limited due to the earthquake.

Collapsed road

At the sleeping base, we slept in a sleeping bag with a silver mat about 2 cm thick on a floor covered with a blue sheet. Food was consisted mainly of retort pouch foods, cup noodles, and canned foods that we brought with us or that our host partners prepared for us. Immediately after waking up on the first morning, I could not move my back, and as I slept on a soft bed every day, I had to suffer through the pain of this. At evacuation shelters where many people rushed in and slept after the earthquake, I heard that those people had to sleep most of the time directly on the floor. It was my first experience not being able to rest by sleeping in such an environment. I was also reminded of how much stress was placed on the people in the affected areas, given the coldness of the snowy Hokuriku region.

Sleeping area

During our activities, we walked around Noto areas and also discovered the extent of the damage. The ground was cracked and uplifted, buildings were half destroyed or collapsed, and it was the first time to see such scene with my own eyes. The Shiromaru area in particular, which was hit by the tsunami, left us speechless. I wondered; "If I had been here, what would I have done? How would I have felt?” I grew up in Shizuoka city where the ocean and mountains are close by and I felt terrible just thinking about it.

Shiromaru area damaged by tsunami

The two main volunteer activities I engaged in were "responding at evacuation shelters" and "checking on non-Japanese residents in Noto. As it was my first-time volunteering in disaster-affected areas, I was fully occupied trying to meet the needs of the ever-changing situation.

Scene of a soup kitchen at one of the evacuation shelters

For the survey of non-Japanese residents, we gathered information from people at evacuation shelters and city halls, contacted employers and interviewed those identified individuals themselves. We felt relieved to learn that all of these people we actually met were "not in crisis" and that their hosts/employers were looking after them. That being said, some issues and challenges remained. For example, we learned that in the case of an emergency, providing relevant information to non-Japanese individuals in a timely manner, and listening and swiftly responding to their needs are imperative. If there had been daily interactions between the non-Japanese residents and the local residents, it might have been possible to care for them and grasp their situations and needs more quickly after the disaster. I felt that connecting non-Japanese residents and local Japanese residents in the region and promoting mutual understanding are important roles that JICA can provide.

Left: Mochizuki

Although it was only for approximately two weeks, I strongly believe that there are certainly areas where JICA can be of help by grasping information and responding to needs in the affected areas. I feel that the importance of "responding on the ground" that I learned in Sri Lanka as a JOCV is important not only in developing countries but everywhere. I also feel that we need to preserve what we have learned this time not on an individual level, but as JICA's knowledge and experience, and keep within our organization "what we can do as JICA in the case of a disaster”.

The needs on the ground are changing daily, but the need for support remains the same, and daily lives for those living in evacuation shelters and in need of support have not yet fully returned to normal. What can Japan as a country which has experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Great East Japan Earthquake, and JICA as an international organization which has provided emergency disaster relief in developing countries, do? I believe that by continuing to stay close to domestic issues, we will be able to find ways to approach the challenges faced by developing countries to materialize a world where "Leave No One Behind".

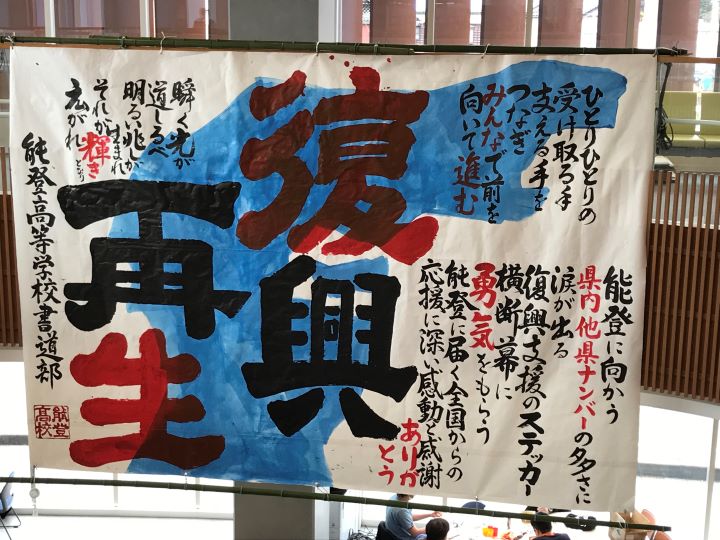

“Reconstruction and revitalization” banner written in Japanese at the Noto city hall

scroll