Volunteer Report "Dealing with child death in Malawi"

2025.04.07

Name:Mariko Kawamoto

Specialty:Public Health

As part of a Public Health volunteer, I have safely reached one year since coming to Malawi at the end of January 2025! When I thought about what to write about for my one-year anniversary, there were many fun and fulfilling things, but I wanted to write about the thing that made the strongest impression on me during my activities, for better or worse. During my first year as a volunteer, I made monthly rounds to the relevant departments to learn about public health activities at Salima District Hospital. One of these is the Nutrition department, which includes an inpatient facility called the Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit (NRU) for infants and children who are at high risk of mortality and require intensive 24-hour medical and nutritional care. In Salima, there are five beds and home craft workers on duty work in two shifts - day and night. They are responsible for growth monitoring (measuring the children's height, weight, and upper arm size (MUAC) to assess their nutritional status) and preparing therapeutic milk.

I was excited to learn what kind of work goes on here, but what I saw was the harsh reality of being in a developing country and one of the poorest countries in the world.

Every day, small children are admitted to NRU. Especially during the rainy season, before the harvest of the staple food maize, there is a food shortage, and the number of children who cannot eat increases. I have no experience working in a hospital in Japan, so I don't know if this is a common occurrence or not, or to what extent. I have never seen malnourished children.

Before studying Nutrition, I never came face to face with people who were suffering from illnesses, such as those in the field of immunization or maternal health, so when I saw children who had actually been hospitalized with malnutrition at NRU, I was shocked, as I had always thought, "There are a lot of healthy children in hospitals and in villages." There were various causes, such as malnutrition causing another infection, or cerebral palsy or stunted growth that prevented them from eating, but the malnourished children were one or even two sizes smaller than healthy children, with arms and legs as thin as tree branches, excess skin around their hips and pelvis, and bones sticking out, making them look very painful. They were just like the starving children in Africa that we see on the news and in textbooks.

The four photos below are malnourished children that I actually encountered in Salima.

A baby drinking treated milk. Her head is the size of a palm, and her body is in a state where the skin is stuck to the bones.

This baby cannot receive the treatment orally, so the baby receives it through a tube in his nose.

After this baby stopped being breastfed, it became difficult to feed him due to a lack of income. As a result, his stomach became bloated and his bones became visible from his hips to legs.

A condition in which the skin peels off as a result of oedema caused by malnutrition.

The mothers were tired from caring for their children, and seemed to lack vitality, so much so that I thought it might be necessary to take care of the mothers' mental health as well. I wanted to ask them many times why they hadn't brought their children to the hospital earlier, and the students on their training even shouted at them, "Mom! Listen to the explanation carefully!!"

As an NRU staff member, what I could do is limited to helping provide therapeutic milk and monitoring the children's growth. However, as I was doing these things and seeing the children every day, the mothers began to accept the novelty of a foreigner in a positive way, and they became open and talk to me. Little by little, the mothers' expressions brightened up, and I felt happy to see them becoming more lively during their time at NRU.

However, the NRU is a place that accepts infants and children who are at high risk of death, so it was a real shock when a two-year-old child in our care suddenly took a turn for the worse and passed away. It seems that his resistance had been weakened by malnutrition and that he died from an infection and dehydration (probably hypoxia as well), but the hospital lacked effective treatments and perhaps the doctors also lacked the necessary skills, so it seemed as if they just checked his condition and did nothing, which made me feel infuriated. I think Japan could have saved the life of the child. Even if people were in a hospital, if there were no medical staff to treat them or medicines, they would have to rely on what they had and would stop trying to save them, and that would be the end of it. The child died quietly without saying a word, his mother was not present, and the grandmother who had been caring for him was crying. Flies and small cockroaches began to gather around the dead child. Then, just an hour later, another mother and child who had been present when the child died in the same NRU were sharing the same bed. Patients keep coming and there aren't enough beds. After this, the grandmother will carry the body back to her village. This is the first death I've faced in Malawi.

However, even in such a situation, and perhaps especially because of it, there are hospital staff members called Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) who work every day to prevent malnourished children from being born. As an example, with the aim of preventing malnutrition in the area under this HAS’s jurisdiction, he works with volunteers living in the villages to conduct a comprehensive survey of the age, weight, and MUAC of all the children in the village, and as a preventative measure, he and volunteers provide dietary advice and daily meals to children who are underweight and have an MUAC of 13cm or less. After 12 days they look at the weight and MUAC gains to see if they are helping the animals grow properly.

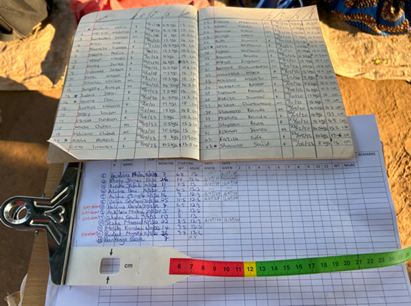

Records of a mass survey of children (top notebook) and a record of children at risk of malnutrition (bottom notebook) Very clearly organized data!

They gather the children and their mothers and hold a cooking demonstration to demonstrate how to make nutritious food (porridge, etc.). They feed the children the porridge and continue this for 12 days.

This activity was carried out by the HSA himself, and I felt his determination to prevent malnutrition in his area. As a public health volunteer, I too have come to accept the current situation, and like him, I have renewed my resolve to focus on the community and work hard to ensure that my daily activities contribute to improving the health of mothers and children in Malawi.

scroll