Volunteer Report "Living with Maize"

2025.05.15

Name:Risa Mori

Specialty:Primary Education

Hello. My name is Risa Mori, and I’m currently living in Malawi as a member of the 2024 First Batch of JICA volunteers.

Today, I’d like to talk about maize cultivation—something deeply connected to the daily lives of people in Malawi.

When I arrived in August, it was the dry season. From the car window on the way from the airport to town, I saw red soil with occasional trees and grass—just the kind of "typical African" scenery I had imagined.

A JICA staff who welcomed me said, “It’ll all turn green when the rainy season comes.”

To be honest, I was skeptical.

↑ The dry season

But six months later, when I passed by the same area, it was covered in lush green maize. I was surprised — “It was true after all!”

↑ The rainy season

In Malawi, nearly 80% of the population are small-scale farmers who grow crops for their own consumption. Through communication with the local people, I learned how maize farming supports their livelihood—and even contributes to well-being.

Living here, I wanted to try living like the locals, seeing life from their perspective. That’s why I decided to try growing maize myself.

Maize is a widely cultivated crop in Africa. It’s resistant to heat and drought, and grows well in sunny areas with moderate rainfall.

Unlike Japan’s long, continuous rainy season, rain in Africa’s wet season falls in short, intense bursts—like buckets pouring down—and then the sun comes out again. This creates an ideal environment for maize growth.

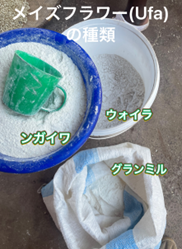

The staple food in Malawi is nsima, made from maize flour called “ufa,” which is mixed with hot water and kneaded.

It looks like potato salad, has a chewy texture, and is eaten with vegetables, meat, or beans. Malawians love nsima so much that there’s a saying: “No Nsima, No Life.”

↑ Three types of ufa (ground maize flour)

↑ Nsima with goat meat and vegetables

I created a small field in a corner of my garden to try growing maize.

My neighbor, a gardener, taught me everything from scratch and helped me along the way. I couldn't have done it without him—so grateful!

↑ My neighbor the gardener

Early December – Making ridges

Using a hoe, I dug up the hard soil and created ridges.

People who grew up in rural area are used to helping on farms from a young age and are very skilled.

↑ Handmade hoe and seeds

↑ Soil preparation lesson

↑ Finished ridges

I planted a hybrid seed variety called DKC80-23, coated in red pesticide to protect it from pests.

In Malawi, there are local and hybrid categories, and this variety is bred for faster growth. I needed only a small amounts of seeds, so I couldn’t buy it in stores—my supervisor kindly shared some with me.

↑ Maize seeds

There are several planting methods.

I used the “Sasakawa method,” planting one seed per hole with 25 cm spacing. This method is widely known in Malawi and comes from the Sasakawa Africa Association (SSA), which has supported African small-scale farmers for over 30 years.

I thought I had to water daily, but the gardener said, “No need—the rain will take care of it.”

Before this, I disliked rain because it caused power outages and flooding. In Japan, a lack of rain didn’t affect access to food or water, so it rarely felt important.

But after planting maize, I started feeling relief when it rained, and concern when it didn’t.

For the first time, I truly understood the phrase “rain is a blessing from the heavens.”

Two weeks later, I saw the first sprouts—vibrant green and full of life. Watching them grow taller each day became my morning routine.

↑ Growing maize

About a month later, I noticed my maize was growing more slowly and some leaves were turning brown. The gardener said it was time for fertilizer.

Problem: I didn’t know where to buy fertilizer.

Using local language, I asked around at the market and finally found a fertilizer store—run by the mother of one of my students, to my surprise.

I learned that fertilizer is sold by weight. I got 500g of NPK fertilizer.

How to apply it

Instead of sprinkling, I poke holes near the base of each plant with a stick and insert the fertilizer. This helps deliver nutrients more effectively. A month later, I added a different mixed fertilizer.

↑ Fertilizing process

Late February – The maize was taller than me, with ears forming and kernels starting to develop. Ants and mantises rested on the leaves and helped the plants grow by improving air circulation.

↑ Maize growing taller than me

The rains continued steadily, and by April it was harvest time.

Since I planted a bit late, my harvest came later than others. I checked the kernels for hardness and harvested them.

I got small, palm-sized maize cobs—my very first harvest!

↑ My first-ever maize harvest

I slowly roasted the maize using a traditional brazier over charcoal. I shared it with the gardener and local friends.

Though only a quarter the size of what locals grow, they said, “It’s sweet and delicious!”

I felt immense joy and gratitude—this was the happiest moment of my time in Malawi. They even said, “You’re a real Malawian now!”

↑ “Karibu” (Culture of sharing food)

This harvest affects the nation’s food supply for the entire year.

Two years ago, a drought caused severe food shortages and even a national emergency. That’s how crucial maize farming is to daily life.

↑ Helping harvest kernels with children

↑ Grinding into flour

↑ Drying under the sun

I only managed three ridges, but local people take care of vast fields—all by hand.

No machines like in Japan. Digging, planting, fertilizing, harvesting, seed collection, drying, grinding—all done manually.

Seeing whole families working together made me admire and deeply wish for successful crops.

“Seeing is believing.”

Maize cultivation allowed me to understand local life and connect with people. It was valuable experience in my life.

Next year, I plan to try growing it again and aim for even better harvest. I already miss the fields of green maize. Lastly, here’s so cute girl with maize!

scroll