Tanaka Chisato

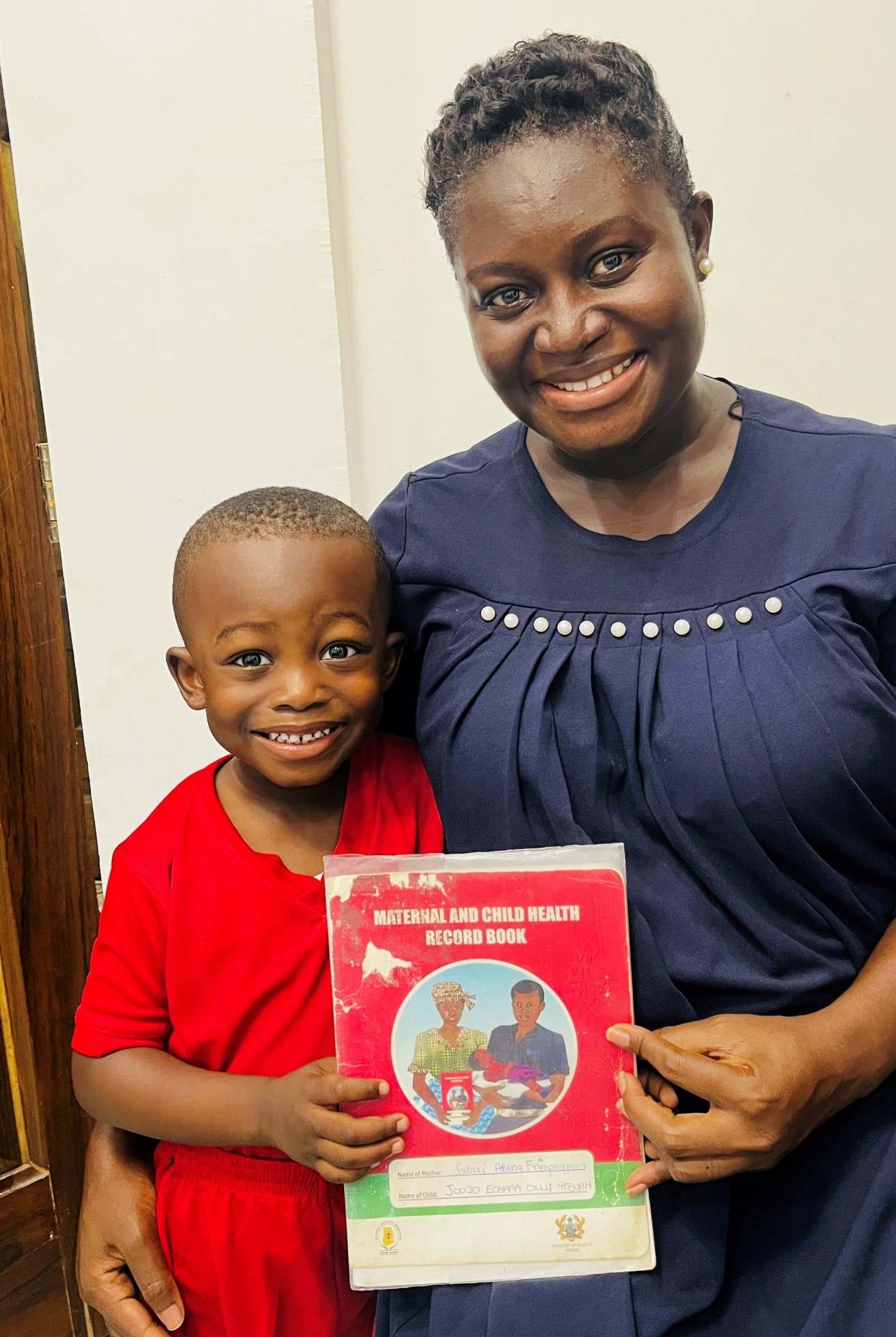

(Hagiwara Akiko shows the MCH Handbook to a mother and child at a health centre near Bolgatanga in Ghana, 2016/ Photo: JICA)

Series : Africa in Focus

In the lead-up to the 9th Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD9) in August 2025, JICA is sharing a series of stories that explore Africa’s challenges and promise. While showcasing JICA’s contributions, the series also brings attention to the broader efforts, ideas and potential across the continent. The first story focuses on maternal and child health.

On a blistering hot afternoon beneath the shade of mango trees in northern Ghana, Hagiwara Akiko crouched beside a group of local residents, gently flipping through the pages of a colourful booklet. It showed a mother breastfeeding her newborn. She wasn’t just showing the booklet; she was observing their reactions. Would the illustration, showing mothers breastfeeding openly, be acceptable in this small Muslim community? Would this offend the elderly?

“Feedback is important to ensure that our content is not offensive and can be widely used,” said Hagiwara.

This wasn’t content for just any booklet. It was for a powerful little booklet known as the Maternal and Child Health Handbook—or simply, the MCH Handbook. First issued in Japan in 1948, the handbook blends health records and a parenting guide. It documents everything from pregnancy check-ups and birth details to child growth charts, vaccinations, and developmental milestones.

For Hagiwara, a senior health adviser with the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), this small book has become her life’s work. She’s spent nearly 20 years adapting and distributing it across the globe—from Palestine to Ghana, Sierra Leone and Liberia— determined to improve the odds for mothers and babies.

Many countries have home-based health records—but Japan’s version stands out by combining records for both mother and child in one place. In many parts of Africa, mothers juggle separate books for themselves, their children, and immunisations. Information sometimes gets lost. Doctors often work blind. The MCH Handbook solves that.

Hagiwara’s journey with the handbook began in Palestine in 2005, with the realisation that her work could also benefit people back home.

There, she and her team, in collaboration with the government, UN organisations (UNICEF, UNRWA and WHO), designed the handbooks from scratch and managed to digitise them for Palestinian refugees—making it possible for children displaced by conflict to retain access to their critical health information and health care.

Through this experience, she came to see JICA’s mission not only as sharing knowledge globally as an equal partner, but also as an opportunity to bring valuable insights back to Japan, such as how best to digitise the handbook.

Another important lesson she learnt in Palestine was that the one-size-fits-all doesn’t work.

Every community has different needs, beliefs, and even climates—all of which need to be taken into account. In Ghana, for example, the handbooks had to be slightly larger than the ones widely used in Japan. Health workers were unused to writing in small notebooks, while they couldn’t be too big either—mothers folded them to fit inside their purses, which damaged the pages.

Hagiwara and her team conducted repeated trials with frontline health workers and mothers to determine the most practical size. They ultimately arrived at an optimal design: compact, lightweight, and suitable for carrying in a purse. They also designed the cover with spot varnish, a protective coating to selected areas of the surface. This helps protect the handbook in hot climates and allows healthcare providers to write the names of the mother and child directly on it.

One of the many mothers using the handbook is Abena Subiri, a 32-year-old auditor in Accra, the capital city of Ghana. Since the day she received the handbook at the hospital, she’s kept it with her everywhere.

“I keep it in my bag and I walk around with it. I go to work with it too,” she said.

(Abena Subiri poses for a photo with her son in Accra, Ghana on May 15th, 2025/ Photo: Linda Okyir)

She even brought it with her when she went into labour.

“It is like a passport,” she said. “It’s actually a requirement…without the book, the doctors tell you that they cannot do anything for you.”

Now expecting her second child, due in September, she reads through the handbook regularly to keep track of her appointments.

The Ghana MCH Handbook is colourful, designed to be easy to use by both health workers and mothers. By colour coding, users can quickly locate information they need without having to read through every page, allowing health workers to navigate the 64-page handbook more efficiently. Orange indicates pregnancy care, yellow is for delivery care, blue for newborn care, and green for childcare. This system helps health workers fill in and retrieve records without flipping through multiple pages.

The MCH Handbooks are also bright, colourful and filled with visuals and diagrams to support women with limited literacy or those who speak a local language different from the handbook’s language. They also feature a playful reward system—mothers receive a star-shaped stamp every time they complete a health checkup for themselves and for their baby.

(The stamp collection page, also known as Continuity of Care Card, is included in the MCH Handbook to track antenatal, delivery and postnatal care, childcare, immunisations, and other maternal and child health services/ Photo: JICA)

In Ghana, a star is seen as the highest form of recognition, Hagiwara explains. As a result, giving mothers stars during their visits serves as a powerful motivator and a source of encouragement.

“It makes you feel special when someone says you’re a star,” said Abena. “It means you’re playing a big role. You are something important. You’re a role model. People look up to you.”

While adapting the handbook to local cultures is essential, Hagiwara doesn’t shy away from gently challenging traditional norms.

In Palestine, where most of the population is Muslim, local midwives encouraged her to include illustrations of husbands actively involved in childcare. Hagiwara embraced the idea. The handbooks depict fathers kneeling down and feeding their babies and girls studying alongside boys—quiet but powerful images that reflect and encourage gender inclusivity.

Building on the success of the handbook programmes in Palestine and Indonesia, the African versions adapted a similar approach. The illustrations now show men accompanying their pregnant wives to health facilities, reviewing medications together, and participating in medical consultations.

(Midwife provides health and nutrition guidance to a pregnant woman and her husband using the MCH Handbook at a health centre near Kumasi, Ghana in 2021/ Photo: Hagiwara Akiko)

These thoughtfully crafted handbooks have led to a dramatic increase in visits to maternity care and have made a significant impact. In 2014, only 20 percent of Ghanaian mothers visited a hospital within two days of giving birth. By 2022, that figure had climbed to 87 percent. This is crucial, as nearly half of all deaths among children under five happen within the first 28 days of life and 70 percent of them occur within the first week of life.

Today, thanks to the handbook’s widespread use, 80 percent of children under five in Ghana have their weight and height regularly checked and recorded.

Knowing a child's date of birth, weight and height allows health care providers to evaluate their growth for their age and identify malnutrition or developmental delays.

But even the best tools can only do so much.

“If no vaccinations or proper health check-ups are provided at facilities, the handbooks are just a piece of paper - there’s no point in keeping records,” Hagiwara said.

“If the handbooks are in short supply or health workers are not properly trained to use them effectively, the potential benefits of the handbook will not be realised. So, producing a good handbook is just the first step of the MCH Handbook programme. We support countries in integrating the handbook into their institutions and sustaining the MCH Handbook programme within their national health systems”, Hagiwara added.

Rural mothers still face significant hurdles in going to health centres and hospitals—travel is costly, families may not always allow mothers to travel away from their villages, work demands can often be high on young mothers, and clinics often lack proper staff.

Hagiwara has also seen firsthand how old customs can become a barrier.

In some Ghanaian communities, women are hesitant to announce their pregnancies early, fearing that revealing them could lead to a miscarriage.

While the World Health Organization recommends at least eight prenatal visits, only about 32 percent of pregnant women in Ghana met that goal in 2020.

(A community health nurse provides a health consultation to a pregnant woman using the MCH Handbook in 2019/ Photo: Hagiwara Akiko)

Still, there is reason for hope.

Hagiwara recalls a moment that stayed with her: a young schoolgirl reading through the MCH Handbook alongside her pregnant mother. For Hagiwara, it embodied everything the project stands for.

“I feel that things are changing. Women are taking charge of their health more, making informed decisions, and empowering themselves,” said Hagiwara.

Today, the MCH Handbook is used in at least 18 African countries and published mainly in three languages (English, French and Portuguese). JICA invests nearly one billion yen (around 6.7 million USD) annually into the improvement of maternal and child health in Africa with various evidence-based interventions including the development and the use of the handbooks.

At 62, Hagiwara, herself a mother of two daughters, remains a quiet force reshaping how the world supports women and children, partnering with UNICEF, WHO, and the World Bank on broader maternal and child health initiatives.

She’s been encouraged by the growing interest from Japanese companies exploring ways to digitise the handbooks in Africa.

“We might see a possible cycle where these Japanese companies pilot their technology in Africa and eventually bring it back to Japan,” she said.

scroll