Tanaka Chisato

(Maruyama Satoko poses for photo with Kuru Art displayed at Koumi Kogen Museum in 2025/ Photo: Suzuki Kazufumi)

Series : Africa in Focus

To mark the 9th Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD9) in August 2025, JICA is sharing a series of stories that explore Africa’s challenges and promise. While showcasing JICA’s contributions, this instalment brings attention to the broader efforts, ideas and potential across the continent.

This story focuses on community development.

After more than a decade working in international roles in JICA and other organisations, Maruyama Satoko left the global stage to settle in a small town in the countryside of Nagano Prefecture, Japan.

The pull was not just its natural beauty, but also the kind of fieldwork she has always cherished — talking, listening, and working directly with local people to solve problems from the ground up.

Her passion for this hands-on approach began more than a decade ago, when she was dispatched to Botswana as part of the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV). Tasked with supporting the indigenous San community move from their ancestral hunting grounds in the Kalahari Desert, she learned lessons that continue to guide her life.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the JOCV programme. Since its launch in 1965, the programme has sent more than 57,000 Japanese volunteers to 99 countries. Their work has spanned agriculture, forestry, fisheries, health, education, and commerce, with volunteers typically spending two years overseas. Many, like Maruyama, return with skills and insights that shape their work back home.

In Botswana, Maruyama’s role as a community development officer was to help women develop income-generating skills after resettlement.

She organised craft-making workshops, but at first many women, who were accustomed to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, showed little interest. Some women arrived late, others did not show up at all. For those long accustomed to a very different lifestyle, the very concept of earning money was unfamiliar.

Rather than push harder, Maruyama adjusted her approach, focusing on those who showed genuine interest. Momentum built slowly, until one woman successfully earned income from the sale of her crafts.

“Telling them in words was not convincing at all, no matter how rational or correct it sounded,” Maruyama recalled. “I learned that showing good practice is what really attracts people.”

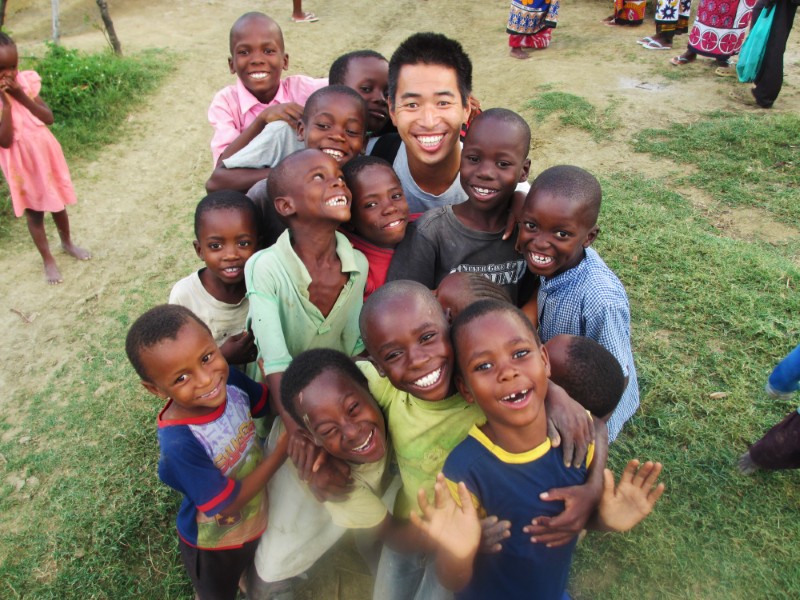

(Maruyama Satoko poses for photo with her local colleagues in Botswana in 2014/ Photo: Nagayama Etsuko)

Miyamoto Keisuke, now a Kanazawa city official, has a similar experience while volunteering in Kenya through the same programme. Children in his village spent up to four hours each day collecting firewood. He introduced a new type of stove that drastically reduced fuel use, freeing children’s time for school. At first, no one believed it would work. But once he demonstrated, families quickly adopted the innovation, cutting children’s workload in half.

“In Kenya, problems just kept coming one after another. I found myself analysing, adjusting, and trying again — plan B when plan A failed, then plan C after that,” Miyamoto said. “I learned that persistence pays off, and that lesson still guides the way I tackle challenges as a city official.”

(Miyamoto Keisuke poses for a photo with local kids in Kilifi town, Kenya,October 2013/ Photo: JICA)

For Maruyama Satoko, the key lesson was empathy. What might look inefficient or impractical, could be deeply meaningful or necessary to others.

For example, some San trainees would seemingly abandon their workshops and not return for weeks. Only later did she find out they had returned to their desert, to be with their families.

“This sometimes disrupted our workflow,” she said. “But in the end, the project was about improving their lives and happiness, not just being efficient.”

Now based in Koumi, a rural town in Nagano with a population of just over 4,000, Maruyama is, as the local vitalisation cooperator, applying the same approach to support its 180 foreign workers and technical trainees. Although they make up nearly four per cent of the town, many locals rarely see them, and are unsure how — or whether — to connect. Maruyama is conducting surveys to understand their needs from Japanese lessons and healthcare to education, long-term settlement, and the accessibility of local transportation.

“Their lives are invisible, as they move only between home and work,” she said. “We need to understand their needs first.”

She is also bringing part of Africa to Koumi. This winter she is organising an exhibition of vivid art prints by San artists, known as Kuru Art. Widely recognized in Europe but little known in Japan, the works will be displayed alongside pieces by Japanese artists with disabilities – a group who, like the San, often create outside formal art institutions.

The exhibition will include a cultural exchange: children in Botswana will choose works by Japanese artists, while local residents in Nagano, including students in Koumi, select their favorite San pieces. Japanese volunteers currently working in Botswana will help make the link.

Miyamoto, meanwhile, has carried the spirit of innovation he discovered in Africa back into his role at city hall. In a workplace where precedent often rules, he has made it his mission to push for new ideas.

“People spend their time analysing what others have done, or how things were handled in the past, and simply repeat it,” he said. “But after Kenya, I stopped thinking about what was done before. Now I focus only on how to bring innovation, how to try something new.”

Among his initiatives was the revitalising of a long-standing international exchange programme in Ishikawa Prefecture, where overseas students stay with local host families. Miyamoto set up dialogue sessions that brought Japanese university students and overseas students together to explore global challenges and the SDGs. Host families were also invited, which encouraged meaningful conversations and deeper connections across cultures. The idea proved so popular that it soon became a highlight of the exchange programme.

He also transformed the town’s classical music festival. Rather than confine performances to concert halls, Miyamoto suggested staging them in unconventional venues such as football stadiums and care homes. By tailoring each performance to its audience, he opened up classical music to broader and more diverse communities.

Of course, his drive for change sometimes causes friction. But Miyamoto embraces the challenge. “Starting something new in a place where change is difficult—that’s where I find meaning,” he said, reflecting on how his experience in Africa ignited his creativity and gave him the courage to take risks.

Today he chairs the JOCV alumni association in Ishikawa Prefecture, organising events such as cultural festivals and mentoring new volunteers. For him, the network is both a lifelong community and a channel for bringing international perspectives into Japanese society.

“I hope to inspire more young Japanese to volunteer abroad, at a time when fewer are choosing to (travel overseas),” he said. “I grew so much as a person through failing and overcoming challenges in Africa. Those experiences last forever.”

scroll