School for All Project in Africa: Data shows dramatic improvement in children’s education

2022.11.18

November 20 is World Children’s Day, established by the United Nations in 1954 to promote mutual understanding among children around the world and improve their welfare.

Parents around the globe want to provide their children with a quality education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, almost 90 percent of primary-school-aged children are not achieving the minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the “learning crisis” by necessitating such measures as school closures.

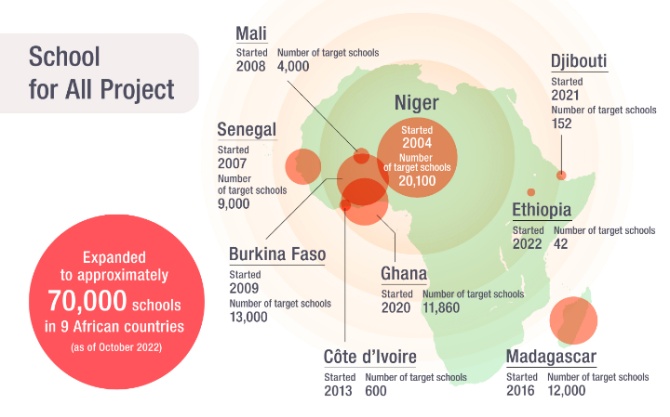

Against such a backdrop, the JICA “School for All” project has dramatically improved the basic academic skills of African children by improving the learning environment for children in collaboration with schools, parents, and local communities. The project, which started in 2004 at 23 primary schools in Niger, has now spread to about 70,000 primary and secondary schools in nine African countries, and its achievements have attracted worldwide attention.

The chart below shows data to illustrate the “School for All” project.

School children in Madagascar attending one of the reading and writing remedial classes supported by the School for All project.

The World Conference on Education for All was held in Thailand in 1990. Following the conference, the goal of “Education for All” was pursued by government initiatives in African countries through the promotion of free education for primary school students.

To ensure that school management reflected community needs, a School Management Committee (SMC) consisting of teachers, parents, and community members—a bigger version of Japanese PTA—was formed in each school. Unfortunately, this did not work as expected. Educational priorities in African countries had been on the elite education for training bureaucrats to support the government, so there was a sense that schools were only meant for the wealthy few. What’s more, village chiefs often served as representatives on the school management committees, so it was difficult to ensure transparency, which also lead to distrust among the locals

JICA set out to create a School Management Committee structure that would promote community-wide information sharing regarding schools. The SMC representatives were democratically elected through a secret ballot, and school action plans were approved at the community general assembly. This allowed the whole community to share information, which spurred interest in school management. Not only parents and teachers but also local people shared the importance of education and support for children’s learning.

That was the beginning of the “School for All” project. The SMCs take initiative in improving the learning environment by building classrooms and purchasing textbooks and stationery through community-wide collaboration. Since the quality and length of classes had also been inadequate, community volunteers and teachers collaboratively deliver remedial classes for children. As a result of these initiatives, basic academic skills in numeracy and literacy improved dramatically.

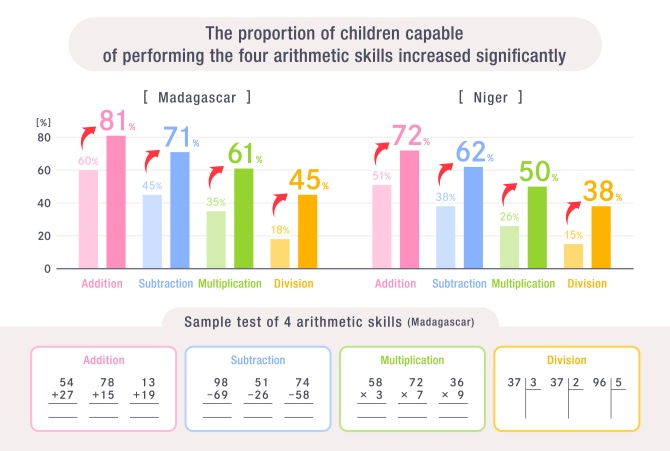

The graph below illustrates the changes in basic academic skills after the implementation of the School for All project for one million students in Niger and Madagascar. Tests of the four arithmetic skills—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—as well as of reading and writing were administered to large numbers of children before and after several months of remedial activities.

In both countries, the number of children capable of performing the four arithmetic skills increased by an average of 24 percent.

Madagascar: Comparison of test results of 75,445 students in 1,027 schools in the 2021 school year, before and after 3–4 months of remedial activities.

Niger: Comparison of test results of 539,786 students in grades 3-6 in 6,758 schools in the 2021 school year, before and after 3 months of remedial activities.

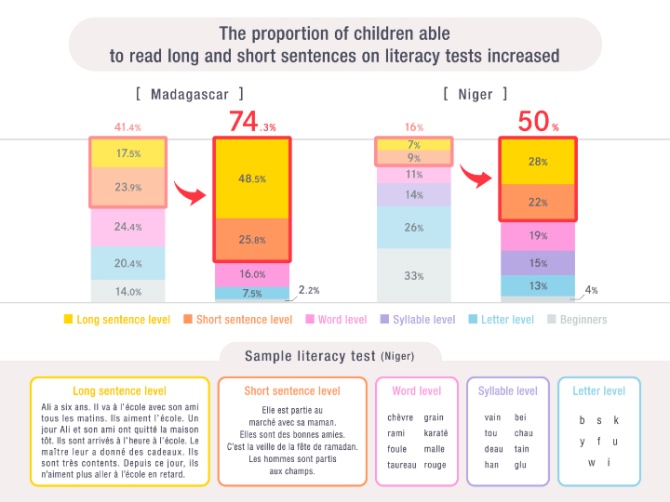

For the reading and writing test, students were presented with examples of letters, syllables, words, and long and short sentences, and tested on their reading comprehension. The different lengths of time spent on supplementary education prevent comparisons between the two countries; however, both countries showed a significant increase in the number of students who can understand long and short sentences. In Niger in particular, the 33 percent of children at the beginner level who were unable to read was drastically reduced to 4 percent.

Madagascar: Comparison of test results of 640,288 students in 6,714 schools in the 2021 school year, before and after 3 to 4 months of remedial activities

Niger: Comparison of test results of 551,441 students in grades 3-6 in 6,758 schools in the 2021 school year, before and after 8 months of remedial activities.

Getting results through measuring proficiency and recognizing setbacks

JICA Senior Advisor Kunieda Nobuhiro has long been involved in promoting the “School for All” project. He explained the background behind the project’s success to date. “There was a great need in the region for such an initiative, led by the desire of parents, teachers, and local people to provide their children with a better education,” he said. “The School for All project was able to meet the needs of that community and provide a concrete solution tailored to the current situation in Africa.”

SMC members at a school in Madagascar, with the school action plan on the blackboard.

Free primary education in Africa picked up pace from the 2000s, and enrollment rates gradually increased. Unfortunately, improvements in the quality of education did not keep up, and in fact, started to decline. Schools were not correctly measuring the children’s levels of proficiency, and classes progressed without a clear understanding of each child’s level of comprehension. Some children felt left behind, losing their motivation to learn and sometimes dropping out of school.

The “School for All” project encourages the SMC to consider each student’s learning level individually. It supports the introduction of instructional methods with remedial classes tailored to each child’s level of understanding and proficiency. By keeping an eye out for setbacks, and including semester-by-semester tests to assess comprehension, the quality of education steadily improved.

Children learn through play at a school in Madagascar, where educational methods are adapted to their academic abilities.

Children who participated in the remedial classes supported by the “School for All” project at a primary school in the Analamanga district near the capital of Madagascar this August commented on their experience.

Fourth grader Jenny said, “I get to learn while playing with others. I wasn’t good at arithmetic before, but now, thanks to the remedial classes, I can do all four operations. I want to continue improving like this, and hope to become a doctor in the future.”

Said third grader Nehemia, “I enjoyed reading the stories. I went home and told my sister what I had learned in remedial class, and we reviewed it together.”

Jenny (right) and Nehemia (left) shared their thoughts on the “School for All” remedial classes.

In 2022, RTI International, a US international research institute, identified Madagascar’s School for All project one of the most successful educational projects in the Asia-Africa region for scaling up in the field of numeracy. It was also introduced in the Financial Times, a UK newspaper focusing on economic affairs.

JICA’s Senior Advisor Kunieda explained that the institute’s appraisal was a recognition of several factors. While the data clearly indicated the improvement of the children’s basic academic skills, the versatility of the model was another positive aspect, as its methods can be deployed in other regions. Costs can also be kept low by using teaching materials available in the community and by utilizing existing teacher training programs.

“The “School for All” project represents a cooperative approach to education in which everyone confronts the issues facing children and works together to solve them,” said Kunieda. “It is crucial that parents and local people are aware of these issues, and that all members of the community work together to help children learn.” JICA intends to work with other development partners such as the World Bank and UNICEF, as well as national governments, to expand this community-based approach to improving education throughout Africa.

Children practicing arithmetic using wooden sticks at a school in Madagascar.

scroll