Rebuilding in the Wake of Nuclear Accidents: Ukrainian and Japanese Researchers Join Hands

2023.01.20

JICA has been working with the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) since 2017 on an international joint project involving Chornobyl and Fukushima. The project’s aim is the effective utilization of zones currently isolated due to nuclear power plant accidents. As part of this project, the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity at Fukushima University invited a young Ukrainian researcher to train at the institute from July to December 2022. This took place after the Russian invasion of Ukraine caused severe damage to Ukrainian research institutions, forcing many researchers to suspend their activities. Researchers from Japan and Ukraine have established close ties through this project with a shared desire to rebuild the areas affected by nuclear power-plant accidents.

The Ukrainian researcher was Dr. Olena Burdo of the Institute for Nuclear Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, who spent four months in Japan with the project.

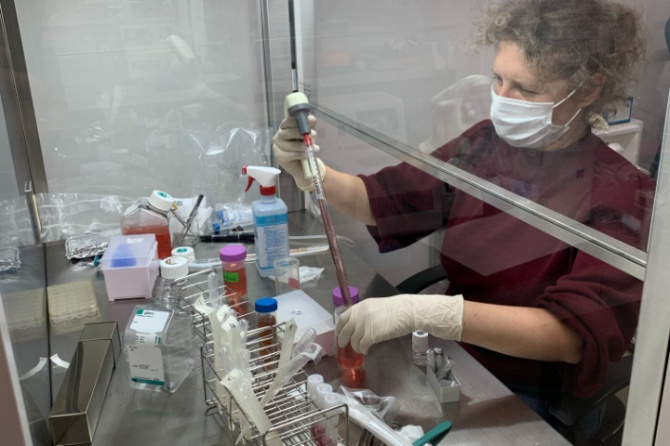

Ukrainian researcher Dr. Olena Burdo at the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity at Fukushima University.

The worst nuclear accident in history occurred in April 1986 at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, which was part of the former Soviet Union at the time. Even after 36 years, the area within 30 km of the plant remains an exclusion zone due to radioactive contamination. In 2011, parts of Fukushima prefecture were affected by radioactivity from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Research and studies on the environmental impact of radioactive contamination has been underway since 2017 as part of the SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development) project. This project uses environmental monitoring techniques to find effective ways to use the Chornobyl exclusion zone.

Dr. Burdo, one of the Ukrainian collaborators on this project, studies the effects of radiation on wild mice living in the Chornobyl exclusion zone. Her training in Japan was based at the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity at Fukushima University, the project's representative research institute. She also collaborated with researchers from the Hirosaki University Institute of Radiation Emergency Medicine and Hokkaido University of Science to hone the skills necessary for her field of expertise, and held discussions with fellow researchers.

Dr. Burdo captures mice, the subjects of her research, in the exclusion zone in Chornobyl, Ukraine.

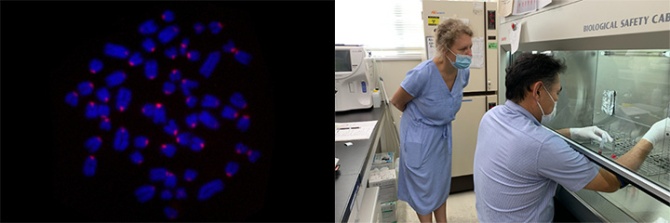

During her training in Japan, Dr. Burdo mastered the FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization) technique for analyzing chromosome aberrations in mice. This advanced technique uses two or more fluorescent dyes to stain chromosomes in order to detect abnormalities. It requires a high level of experience and knowledge.

Since the rate of chromosome aberrations increase in relation to an increase in the amount of radiation exposure, the chromosome aberration value can be used to determine how much individual sample has been exposed to radiation. In the case of low-dose exposure, more than 1,000 cells per mouse must be analyzed to detect chromosomal aberrations. The FISH technique can not only reduce the analysis time to less than one-tenth that of the conventional one-color staining method, but improves the accuracy of the analysis.

“I heard about this technique while in Ukraine but had never practiced it. I am grateful for the support of the many Japanese researchers who gave me the opportunity to learn it,” says Dr. Burdo. “I intend to use the skills I have acquired to analyze the chromosomes of mice living in the Chornobyl exclusion zone. This will provide clues as to how humans would be affected if the exclusion zone were to be reopened for use.”

(Clockwise from top) Dr. Burdo, Prof. Miura Tomisato of Hirosaki University Institute of Radiation Emergency Medicine, and others capture wild mice in an exclusion zone in Namie Town, Fukushima Prefecture; Dr. Burdo studying analysis methods at Hirosaki University; Another training session with Associate Prof. Nakata Akifumi of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hokkaido University of Science: Removing cells from captured mice. Project Lecturer Ishiniwa Hiroko (right) of the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity at Fukushima University also participated in this training; Mouse chromosomes stained using the FISH technique, viewed with a fluorescence microscope.

Finding effective ways of using the Chornobyl exclusion zone is one of the Ukrainian government's key plans for the country's economic development. The government is considering the construction and utilization of radioactive-waste storage facilities, reprocessing facilities, and renewable energy facilities, etc. in the future. To realize this, it is essential to learn how the environment in this area impacts humans.

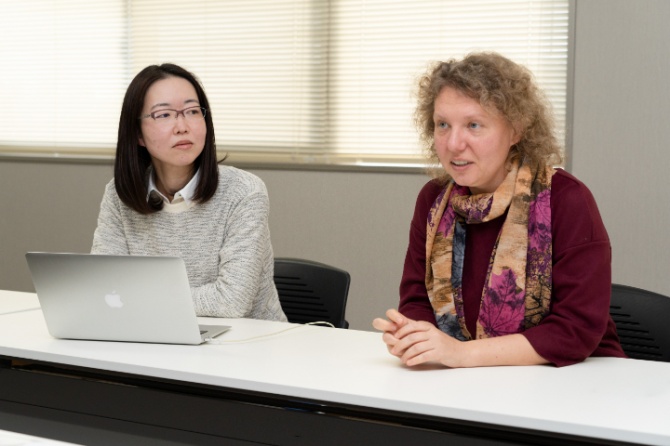

“Dr. Burdo's eagerness to learn and absorb everything has had an impact on my own mentality,” says Ishiniwa Hiroko, project lecturer at the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity at Fukushima University. Organizing and hosting Dr. Burdo's training program in Japan helped Ishiniwa realize how fortunate she was to be in an environment where she could conduct research freely.

The Institute for Nuclear Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, where Dr. Burdo is based, was considered a potential target of the Russian invasion, and immediately closed for about three months. “We were afraid of being attacked, so it was a tense situation, always wondering how we would secure food and survive. We were unable to concentrate on our research,” Dr. Burdo says.

Dr. Burdo (second from the right) took refuge in the suburbs of Kyiv after the invasion.

It was in those difficult times that she learned about the opportunity to continue her research in Japan, and she felt it was “like a dream come true.” Dr. Burdo spent four months working with Japanese researchers. “It was a valuable time, not only because I was able to immerse myself in research, but also because I was able to lead a normal life and ponder deeply about my future,” she says.

Although the situation in Ukraine remains difficult, with power outages being a regular occurrence, Dr. Burdo resumed her research activities in Chornobyl after returning in December. She is pursuing her research while overcoming adversity, and Project Lecturer Ishiniwa wishes her all the best. “I will continue to support her. I sincerely hope that we will be able to do research together again,” Ishiniwa says.

Like Dr. Burdo (right), Project Lecturer Ishiniwa Hiroko (left) of the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity at Fukushima University studies the effects of radiation on wildlife. The two scientists did research work together in Ukraine in 2018 and 2019.

Professor Nanba Kenji is the director of Fukushima University’s Institute of Environmental Radioactivity (IER). “Prior to the Russian invasion, we were conducting a survey with people stationed in the Chornobyl exclusion zone under strict radiation-dose control measures,” he says. “The Ukrainian government's policy on the effective use of the exclusion zone had begun to take shape through such monitoring data, which I think is a major achievement.”

The project included plans to conduct a joint survey in Ukraine in March of 2022, but this was halted by the invasion. When project members heard that the Chornobyl nuclear power plant had been occupied and that the computers and monitoring equipment used for research had been destroyed, they rushed to provide replacements. They were also able to provide a fluorescence microscope for use with the FISH technique, which they expect will be used for various technologies in Ukraine in the future.

“Of course, we will share our findings from Fukushima with Ukraine,” says Prof. Nanba. “But we have also learned a lot from Chornobyl's experience. Although I don't like to think about it, we must continue to research all contaminants in case of another nuclear accident, which could happen anywhere. Research at Chornobyl is very important for Japanese researchers as well.”

Professor Nanba believes that continuing to measure environmental radiation levels will reveal the movement not only of radioactive materials but also of related materials, which will lead to a better understanding of the connection between the environment and animal life. He says that the data obtained through the project can be widely used for the future development of agriculture and forestry.

Research activities in Ukraine continue to be a challenge. Fukushima University is now hosting a doctoral student from the National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, who joined the project in December 2022. “We will continue to support Ukraine's research and human resource development in the field of environmental radioactivity,” says Professor Nanba.

Nanba says that in addition to obtaining scientific data, project participants will leverage the network of researchers and strong relationships of trust that they have cultivated through their joint research to prepare for what may come next. Though this project is scheduled to end in March 2023, researchers will continue working hand in hand on research that links Chornobyl and Fukushima to realize a better future.

scroll