Bangladeshi IT Engineers in Regional Japan: International Cooperation That Fills Needs in Both Countries

2023.02.22

Bangladesh has abundant IT talent but insufficient jobs, while outlying cities in Japan suffer from a dire shortage of IT engineers. Seeing opportunities to meet the needs of both, JICA pieced together separate initiatives, initially launched 14 years ago, to create a new type of international cooperation project. This has attracted great interest and has even become the subject of a manga. To learn more, JICA spoke with two leaders of the project and a Bangladeshi IT engineer who now works at a Japanese company.

JICA’s IT human resource development project was born 14 years ago in 2008 out of the desire of Japanese computer specialists working as Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCVs) in Bangladesh to bolster the employment opportunities of talented, local youths by establishing a system of certifying their qualifications.

“Many young Bangladeshis speak English, they’re smart, and they’re very talented,” says Kano Tsuyoshi, a JICA staff member at the time who eventually took over the project from JOCV members. “Before the project’s launch, however, their career prospects were poor because Bangladesh lacked a national certification program for engineers.” Kano learned IT as a student. From personal experience, he knew that having a marketable skill could lead to big advances in one’s career.

For about five years from 2010, Kano Tsuyoshi led the project as a JICA staff member from both JICA’s headquarters and the Bangladesh office. Currently an associate professor at the Kanazawa Institute of Technology, he is still actively engaged in the project as a researcher.

To resolve the dilemma, JOCV members began exploring the possibility of making use of an IT certification test called the Information Technology Engineers Examination (ITEE). The ITEE is taken by 430,000 people a year in Japan, making it the largest such exam in Asia. The members hoped to introduce the ITEE to Bangladesh so that employers would feel more confident in hiring the country’s young engineers.

The project involved many stakeholders, such as a local association of IT companies, the University of Dhaka, and Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI). Coordinating their many interests was not easy, but a big breakthrough came when JOCV members had an opportunity to meet with then Minister of Science and Information and Communication Technology Yeafesh Osman. They knew he was very fond of “kobita”, a form of Bangla poetry. So they created a kobita expressing the need for an IT personnel development project.

The strategy worked, as the mood in the room changed instantly when the volunteers started reciting a kobita in the local language titled “Building a Bridge between Japan and Bangladesh’s IT Sector.” After a brief pause, the minister replied in verse, “Our ardent wish is for many people to cross this bridge.” Kano says, “This was an excellent example of JICA’s field-oriented approach. We’re focused on being in the field ourselves, living among the people and learning about and respecting their culture. I think this really touched the minister’s heart.”

Presenting a “kobita” to Minister Yeafesh Osman.

The minister’s backing helped to move the project forward. JICA designated it as a Technical Cooperation Project in 2012 and began a trial the following year. On the day of the exam, a “hartal” (strike) broke out, however, and public transportation came to a halt.

But project members did not give up. Kano, who had been directly in charge since 2012, and his colleagues hired rickshaws to deliver the exam to the test site. Despite worries that nobody would show up, 158 of the 332 applicants made it to the venue—including those who came on foot. “We were thrilled,” Kano recalls. “The Japanese examiners arrived a day early and spent the night at the test site. I felt greatly relieved when we actually got through with the exam.”

The trial ITEE examination in Bangladesh, where test questions were delivered by rickshaw.

Following the trial, Bangladesh formally joined the Information Technology Professionals Examination Council (ITPEC) in 2014. It is now one of six member countries in the council. The implementation of the ITEE has enabled Bangladeshi youth to pursue careers as IT engineers in countries around the world.

Bangladesh’s accession ceremony to ITPEC membership.

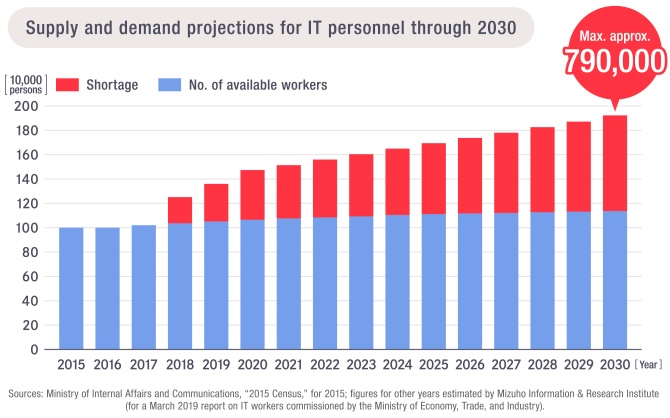

Unlike Bangladesh, Japan is beset by population aging and a severe shortage of IT workers. According to a study published by METI in 2019, the shortfall of such workers in Japan could reach as high as 790,000 by 2030. This has raised serious concerns about delays in the development of IT services and potential risks to information security.

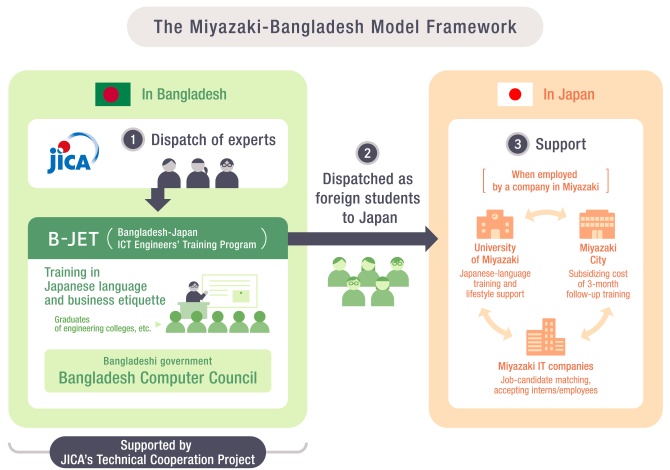

The shortage is especially acute in outlying areas of the country, but one municipality that has been proactively addressing this issue is the city of Miyazaki on the island of Kyushu. To attract IT companies and prevent an exodus of talent, it created a program to invite IT personnel to the city from Bangladesh by teaming up with a local company providing overseas e-learning services, the University of Miyazaki—which has a robust Japanese-language-education program—and JICA.

Playing a pivotal role in linking the city with JICA and in developing what has come to be known as the Miyazaki-Bangladesh Model was Tasaka Shinnosuke of the University of Miyazaki. “I think the model succeeded because, for one, there was recognition on the Miyazaki side that the shortage of IT workers presented a serious challenge,” Tasaka recalls. “Another factor was that clear incentives and responsibilities existed for all stakeholders—the hiring companies, the local government, and the university—prompting them to be engaged in a proactive manner.”

Having worked for the JOCV and an education company, Tasaka Shinnosuke was instrumental in creating the Miyazaki-Bangladesh Model. He is currently promoting the Bangladesh IT personnel project as a program-specific professor at the University of Miyazaki.

The initiative in Miyazaki has led to 24 businesses in the prefecture employing more than 50 IT engineers from Bangladesh between 2017 and 2022. These numbers are the second highest after Tokyo, prompting local governments and companies from all over Japan to make inquiries and visits.

Another factor behind the success in Miyazaki was the Bangladesh-Japan ICT Engineers’ Training Program (B-JET), a JICA project launched in 2017. B-JET is a training program for Bangladeshi IT engineers who are interested in working in Japan. It offers instruction in the Japanese language, business etiquette, and other skills required in the Japanese job market. When JICA ended its support for the program in 2020,* 280 people had completed the course, of whom nearly 70% (186) were employed as engineers by companies in Miyazaki and other parts of Japan.

*The program has continued without JICA’s assistance under the initiative of the University of Miyazaki, North South University in Bangladesh, and private companies.

B-JET participants learn the language and culture of Japan.

One such IT worker is Hossain Muhammad Ramzan, who is employed as a programmer for a systems development company in Miyazaki. He was among the second group of B-JET student to come to Japan, arriving in 2018 at the age of 25. When asked why he wanted to work in Japan, Ramzan said, “My dream is to start my own business one day, so I wanted to acquire advanced IT skills. In Japan, I can not only learn those skills but also feel comfortable since it’s an Asian nation. It so happens that a bridge near my home had been built with JICA’s support, so I had a very favorable impression of Japan. When I learned about the B-JET program, I decided to apply right away.”

As for Japanese business etiquette, he has been impressed by the importance attached to punctuality and close communication with one’s team. Thanks to the lessons provided through B-JET, he says, relations with his bosses, colleagues, and customers at his current workplace have been very smooth.

“My encounter with B-JET was a life-changing experience,” Ramzan comments in fluent Japanese. “I’d like to work in Japan for another 10 to 20 years and then start a business, using my network and experience to build bridges between Bangladesh and Japan.”

Hossain Ramzan (pointing to the screen in the photo at right) has been in Miyazaki for about four years ago and is now working for an IT company called Spark Japan Co., Ltd.

Given the shortage of IT personnel, Japanese businesses see great value in being able to hire outstanding IT engineers who speak the language and are familiar with local business customs. The presence of Bangladeshi workers has also helped revitalize a number of companies.

This is not to say, though, that the initiative has not been without its challenges. “In the beginning, some local residents mistook these engineers for unskilled labor or weren’t sure how to relate with foreigners who suddenly appeared in their midst,” Tasaka admits. “However, as the number of young Bangladeshis with a strong desire to work in Japan has grown, the community has begun to open up and welcome the newcomers, giving locals rare opportunities for cultural exchange.”

“I hope many more young people in Bangladesh will be able to take advantage of opportunities to develop their skills,” says Kano. “The numbers of people who have opportunities to work abroad are still limited. By acquiring basic IT skills, more young people in rural areas and women, too, may be able to broaden their opportunities for employment at local companies.”

The efforts outlined above point to a new approach to international cooperation that enables the resolution of social challenges in both the donor and recipient countries: namely, a shortage of IT workers in Japan and a lack of employment opportunities in Bangladesh. “The lessons learned from this project can be applied to many other areas besides the IT sector,” Kano says. “By understanding each other’s needs more, we can also identify complementary strengths in developing new and better forms of international cooperation.”

scroll