Sustainable and Equitable Water Management That Promotes Well-Being

2024.05.15

Water is essential for human life and economic activity, but many parts of the world are now suffering from a serious water shortage. JICA is thus promoting initiatives aimed at giving everyone equitable access to this indispensable resource. These efforts, called integrated water resources management, can contribute to the achievement of many of the SDGs and are expected to attract great attention at the World Water Forum, to be held in Indonesia in May.

A mosque in Jakarta, Indonesia, that sank into the sea after excessive groundwater pumping caused land subsidence.

A World Bank report noted that the stably available supply of global water resources was 7% short of water demand for household use, agriculture, and industry in 2010. And it projected that the gap would grow to 40% by 2030. The main causes, according to Nagata Kenji, JICA’s Senior Advisor on Water Resources, are not just underdeveloped water infrastructure, climate change, and urban population growth but also competing interests over limited resources.

Nagata Kenji is JICA’s Senior Advisor on Water Resources who has worked on development cooperation projects in the fields of water resources and disaster prevention in over 40 countries.

When a dam is built upstream, for example, it can disrupt the downstream ecosystem by changing the flow of water. It can also result in riverbed degradation and erosion, as sediment no longer moves downstream, causing saltwater intrusion. And land subsidence may occur due to massive groundwater pumping when water cannot be drawn from downriver areas. Any attempt to secure and use water resources is sure to have downstream consequences, as people’s interests collide. Even if effort is made to avoid such conflicts, manipulating nature to serve human needs will likely prove quite difficult.

“Water resources may be naturally scarce in regions that get very little rainfall,” Nagata says. “But quite often, shortages can also result from competing interests—between people, between upstream and downstream, between communities on opposite sides of a river, and between humans and the ecosystem. Reconciling such differences may therefore be an effective way of alleviating many water-related problems.”

The challenge facing many countries is achieving an optimum balance between environmental protection and water resources development. Integrated water resources management (IWRM) is one approach that could provide a comprehensive solution to securing sustainable water resources and water supply while mitigating water-related disasters. It is a framework for systematic and comprehensive water management to maximize the benefits of water in an equitable manner while preserving the natural environment and ecosystem and coordinating the interests of various water-related stakeholders and organizations.

One example of JICA’s development cooperation that incorporates the IWRM approach is a project to halt land subsidence in Indonesia, where the World Water Forum is being held in May this year. Some areas of the capital city of Jakarta have sunk by up to 4 meters since 1970, causing great damage from flooding and storm surges.

Seawater floods into coastal areas of Jakarta during high tide due to land subsidence. (Photo: ardiwebs/Shutterstock.com)

“In Japan, it’s taken for granted that declining ground surface elevation is caused by excessive groundwater pumping,” Nagata notes. “But researchers in Indonesia have argued that other factors may also be involved, such as urban loading and plate tectonics. It’s also important to consider geological differences between Jakarta and Tokyo. The lack of consensus on the causes had hindered efforts to advance countermeasures. So there was a need to present convincing scientific evidence to foster a common awareness among local officials, researchers, residents, and businesses and to come up with measures that all regional stakeholders could agree on.”

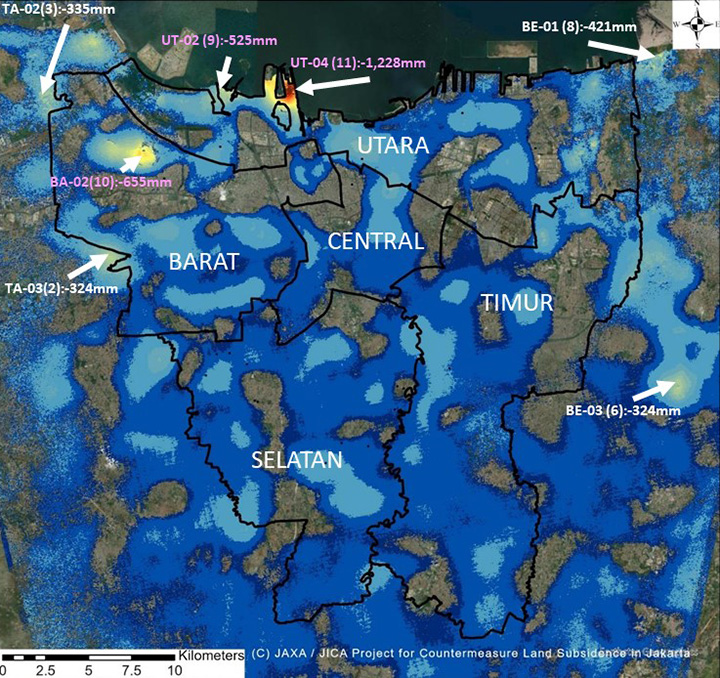

To analyze the causes of land subsidence, Nagata and his team used data collected by the Advanced Land Observing Satellite Daichi of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). They also installed observation wells to record subsidence and groundwater levels and surveyed the amount of groundwater that was being extracted. These monitoring efforts revealed that land subsidence was most pronounced in areas where excessive groundwater was being pumped, such as near factories and major shopping malls. “Our findings helped forge a common understanding of the causes among the stakeholders,” Nagata says, “leading gradually to steps to address this problem. Legal measures were enacted for the drilling of wells, as well as the use and registration of groundwater, and alternative water sources were secured.”

Analysis of Daichi’s image data from 2007 to 2017 revealed the distribution and magnitude of subsidence in Jakarta. The areas highlighted in red and yellow experienced the greatest subsidence, which is measured in millimeters.

Another factor contributing to the fostering of a common awareness was the opportunity by Indonesian officials to see firsthand the towering embankments in Tokyo Bay during their training in Japan. Tokyo’s postwar economic development and urbanization caused land to sink by up to 4.5 meters through the 1970s, resulting in some neighborhoods falling below sea level. Levees and water pumping stations thus became indispensable to prevent flood damage.

“Everyone was amazed when we took them to view the huge levees in Tokyo Bay from a ship,” Nagata recalls. “Without those embankments, Tokyo would be underwater. Once the ground subsides, it will never rise back up, so if Jakarta sinks any further, super levees like those in Tokyo would need to be built and maintained forever into the future. Acting quickly is the best way to keep costs down, and I think this realization led to a change in awareness among the Indonesian stakeholders.”

Land subsidence and groundwater levels continue to be monitored at many observation wells in Tokyo even today, even though subsidence is no longer a concern. Such ongoing efforts further prompted Indonesian officials to take action. The key to promoting IWRM, Nagata emphasizes, is for “all parties concerned to have a common awareness of the issues involved.”

Indonesian government officials learned about the ideas behind IWRM and Tokyo’s land subsidence countermeasures during a training program in Japan.

Today, the mechanism of land subsidence in Jakarta has been clarified based on scientific data, and future projections have become possible. There is also greater understanding of how land subsidence increases flooding and storm-surge risks. The government of the Special Capital Region of Jakarta is pushing ahead with the construction of offshore levees and is promoting the registration of wells, cracking down on illegal water withdrawal, and encouraging factories to relocate from sinking areas. These efforts are expected to spread to other areas of Indonesia in the future.

“Even when using the IWRM approach, it can be a real challenge to integrate the interests of all stakeholders—people and organizations that benefit or are adversely affected by water, as well as government departments responsible for policies on water, the environment, and economic development,” Nagata admits. “But it’s not impossible. The first step is to clearly identify the water-related issues in the region and who are affected. We then need to get everyone involved—local residents, relevant government agencies, and researchers—in discussing what should be done. And once agreement is reached, we have to implement the necessary measures. IWRM is much more than a mere concept or an unattainable ideal; it’s a very practical approach to managing water resources.”

Following successes in Indonesia and Bolivia, Nagata is now engaged in implementing IWRM projects in Cuba and the Philippines. Projects like these are aimed at identifying local water-related issues, achieving successes one by one, encouraging legislative reforms to ensure the continuity of such initiatives, and ultimately contributing to sustainable development. Among the various outcome targets under Goal 6 (“clean water and sanitation for all”) of the SDGs is “implement integrated water resources management at all levels.” Almost all countries around the world are thus now promoting policies to improve water resources management.

JICA cooperated with an IWRM capacity-building project in the municipality of Cochabamba, Bolivia, where large-scale protests broke out in 1999–2000 over the privatization of water services and skyrocketing prices.

“Simply put, the goal of IWRM is to promote a sense of well-being through water,” Nagata asserts. The broad sharing of such sentiments will surely boost IWRM’s role in securing sustainable water resources for all.

scroll