JICA Volunteer Coaches Take On an Olympic and Paralympic Challenge

2024.07.22

Athletes around the world are preparing to compete in the upcoming 2024 Summer Olympics and Paralympics to be held in Paris. Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers are coaching, among others, a table tennis player from Vanuatu and a visually impaired judo player from India. We spoke to these volunteers about their coaching styles and their aspirations for the athletes at the Games.

Photo: Hethers/ Shutterstock.com

Vanuatu is an archipelago of 83 islands that stretches about 1,200 km from north to south, about 1,800 km east of Australia. This year, the 33-year-old Vanuatuan Priscilla Tommy will be making her second Olympic appearance—her first since the 2008 Beijing Games. Takashima Satoshi, a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer (JOCV), has been coaching the Vanuatu national team since April 2023, and is helping develop Tommy’s skills.

Priscilla Tommy (left) and Takashima Satoshi. Takashima’s table tennis career has spanned his middle school, high school, and college years. After graduation, he spent eight and a half years as a sports instructor in the UAE and Bahrain under the auspices of the Japan Foundation. Following his retirement at 60, he has served as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV), coaching Jamaica’s national team from 2017 to 2019 and currently Vanuatu’s national team.

Tommy won the gold medal at the Pacific Games in November 2023, a regional competition held every four years in Oceania. She went on to win all four matches at the Olympic Oceania Qualifiers in May 2024 and secured a spot in the Paris Olympics.

Takashima’s dedicated coaching has contributed greatly to Tommy’s success. He created a unique training program for her and provided guidance based on his analysis of past performances of players from other countries.

Takashima describes Tommy as a “smart player who can use analysis to improve her performance.” Tommy missed the 2012 and 2016 Olympics because of child-rearing and other commitments, and the COVID-19 pandemic prevented her from participating in the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. From November 2019, the pandemic made it impossible for her to practice, as she was living on an island with no table tennis facilities, some 400 kilometers north of the capital of Port Vila. In September 2023, just two months before the Pacific Games, she moved in with her cousin in Port Vila and began training daily with Takashima.

“She is able to compete at a high level because of her solid foundation, despite a lack of practice,” says Takashima. “She is a rare defensive chopper in Oceania, with very large hands and feet, which is her strength. Her honest approach to the training program I designed also contributes to her strength.”

Takashima went on to note that the table tennis environment in Vanuatu is far from ideal. “There is no dedicated training facility,” he says. “We practice in a gym with four tables that is shared with other sports. Last March, two massive cyclones damaged the windows and roof, letting in rain and wind.”

Tommy being coached by Takashima.

The gymnasium with four table tennis tables where the Vanuatu national team practices.

Vanuatu has a table tennis federation but lacks an office, and Takashima is the only coach. Volunteers staff the federation; Tommy’s cousin, Anolyn Lulu, an active table tennis player who competed in the London 2012 Olympics, serves as both federation president and Tommy’s manager. Despite these challenges, Takashima was able to provide passionate coaching while improving the training environment by arranging for the arrival of balls donated by the vice president of the Japan Table Tennis Association.

These efforts powered Tommy’s remarkable performance in last year’s Pacific Games and the Olympic qualifiers earlier this year. She was initially reluctant to change her playing style because of her strong performance, but after securing her Olympic spot, she began incorporating Takashima’s advice in order to defeat stronger players. She is now practicing using both faces of the racquet with different types of rubber and has adopted a more aggressive style of play.

This is Takashima’s first experience as an Olympic coach, and he is excited about accompanying Tommy to Paris. “I hope she can get through the first match,” he says.

Tommy and Takashima shaking hands after she won the final match of the Olympic Oceania Qualifiers, which secured her spot in the Olympics.

Vanuatu’s national team members coached by Takashima. Tommy is second from the left, and her cousin Lulu is fourth from the left. Takashima intends to focus on developing young talent during the remainder of his term.

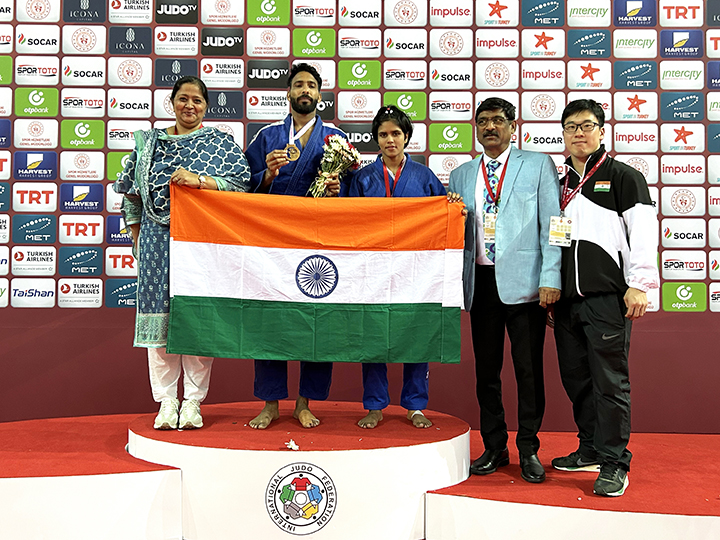

Kapil Parmar and Kokila, two Indian representatives in visually impaired judo, have qualified for the Paralympics for the first time. Their coach, Nagao Soma, is a JOCV with the Indian Blind and Para Judo Association and has been guiding India’s para judo national team since March 2022.

Kapil Parmar (third from left), Kokila (second from left), and Nagao Soma (left). Nagao began practicing judo in elementary school, eventually competing in the Osaka High School Championship and placing third. As captain of his university judo team, he was inspired by the determination of local athletes while teaching judo in India through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ sports diplomacy project. This led him to request a JICA volunteer assignment in India. In addition to coaching the para national team, he also teaches the sport at a local dojo.

Parmar, 23 years old, excels at sweeping throws because of his height and long limbs. Kokila, 20, is smaller, and uses a style that involves getting into close quarters with her opponents. Nagao coaches each of them in a way to utilize their unique characteristics and strengths.

“When I first saw the national team practice, I honestly thought, ‘Can they compete in a world tournament?’” Nagao says. “They didn’t even understand basic movements. I realized I had to teach them both the technical and mental fundamentals.”

Nagao says that the number of able-bodied judo practitioners in India is low compared to the large population. He points out that the recognition of the sport is far from sufficient, which is often confused with karate. The history of para judo is also short, with the Indian Blind and Para Judo Association established only some 14 years ago. There were no high-level coaches previously, so Nagao patiently and repeatedly taught the basics.

Nagao coaching Parmar. In visually impaired judo, the matches always begin in a grappling position.

Nagao instructing at a local dojo, where he teaches 20 to 30 students, ranging in age from elementary school levels to around 20 years old.

Some athletes, however, were not satisfied with repetitive basic training. Nagao sensed that their motivation was low and often felt he had to force them to practice. His initial excitement about the new environment and experiences was replaced by anxiety and frustration with the athletes’ attitudes toward training. It was his first experience coaching para judo, and he was also finding the best way through the process.

“I wondered why they didn’t realize that the training was for their benefit,” Nagao says. When he tearfully consulted the judo association, he was told to stop being anxious. “This is India,” he was told. Those words eventually helped him shift his mindset to respect the Indian athletes’ ways of thinking and their approach to training.

Under Nagao’s instruction, Parmar and Kokila saw significant improvement both technically and mentally. In December 2022, Parmar won the Tokyo International Open Tournament for visually impaired judo, marking the first international victory for an Indian judoka, including able-bodied competitors. Kokila finished as runner-up in the same tournament. In the Asian Para Games in October 2023, they earned accolades when Parmar secured second place and Kokila took third. Prime Minister Modi even praised and encouraged their achievements on social media, raising India’s expectations for them.

“I am delighted when they thank me after winning a medal,” says Nagao. The upcoming games will be his first time accompanying athletes as a Paralympic coach. When asked about their goals, he confidently states, “Kapil will definitely win gold. Kokila will also bring home a medal.” He shows his absolute trust in his athletes with a smile.

In April 2024, Parmar won the International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA) Judo Grand Prix and Kokila finished fifth, gaining momentum before the Paralympics. Nagao extended his contract by nine months and will continue coaching in India until December. After the Paralympics, he plans to lay the groundwork for new training methods that will help athletes adapt to the classification changes taking place in visually impaired judo before the next Paralympics.

Members of the JOCV not only train and grow developing countries’ top athletes for the Olympics and Paralympics but also provide opportunities for everyone to fairly and equally participate in sports. JICA encourages sports participation to boost self-esteem, especially among people with disabilities and women, and promote social inclusion.

Sports have the power to connect people beyond language, race, ethnicity, age, and ability. Through sports, JICA strives to promote peace-building efforts to foster interaction between divided communities and ethnic groups. JICA will continue to leverage “the power of sports” in its cooperative efforts to expand people’s potential and realize a peaceful society.

scroll