Remote Support for Mali’s “School for All”: Promoting Learning for Children in Conflict Regions

2024.11.15

Children are being deprived of educational opportunities in growing areas of the world today due to armed conflict, both between and within nations. In the West African country of Mali, which has been in a socio-political crisis for many years, an initiative is underway to remotely implement a long-running JICA project in Africa called School for All. This article looks at the pioneering efforts the project is making in Mali ahead of World Children’s Day on November 20.

The School for All project is a JICA initiative to promote children’s learning by collaborating with schools, parents, and the local community, rather than entrusting the task solely to the government. It was launched in 2004 with 23 primary schools in Niger and has since expanded to approximately 70,000 primary and secondary schools across 11 African countries. The project in Mali began in 2008.

“I’m often asked why the local community needs to get involved in children’s education,” says Iwata Morio, a member of a team of experts supporting the School for All project in Mali. “It was only recently that primary education became widely available in West Africa, and many parents never had a chance to go to elementary school. For that reason, parents have a strong desire that their kids receive an education and are committed as a community to supporting learning. The government faces severe fiscal constraints, though, and this makes cooperation with parents and the local community essential to sustaining primary education.”

Since Mali’s Ministry of Education adopted the initiative, Iwata and the ministry staff have faced a great challenge in moving the project forward, as they have had to deal with two coups and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Iwata was dispatched to Niger as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer in 2001 and joined the School for All project after working on educational assistance in Niger and Senegal. He has been the project’s JICA expert in Mali and Senegal since 2011 and is currently supporting Mali’s project remotely from Senegal.

The first step in implementing the project involves having residents elect members of the School Management Committee, usually consisting of the principal, parents, and community representatives. “We met many times to painstakingly discuss with our counterparts in the Ministry of Education how we can implement this new initiative in ways that were suited to conditions in Mali to ease any concerns people may have about it,” Iwata explains.

In 2012, when the number of participating schools had expanded tenfold from 156 at the start of the project to about 1,500, a military coup took place in the Mali capital of Bamako. The School for All model had been officially adopted by the Ministry of Education and was about to be expanded to primary schools nationwide, but the coup forced all JICA experts to evacuate from Mali.

Residents voting in the election for representatives of the School Management Committee. In Mali, the village chief’s family has traditionally held important local positions. But members of the committee for the School for All project are voted anonymously by parents and residents. Introducing this democratic process has become a key factor in the success of the project.

Five years after the coup, as political stability slowly returned, efforts were made to relaunch the project. During the interim, Mali’s Education Ministry had managed to expand the School for All initiative to 4,500 schools with the assistance of various support organizations, but additional help was needed to ensure its sustainability. To enable its implementation even when experts were again forced to evacuate, Iwata’s team chose to pursue the unprecedented option of supporting the project in a fully remote way.

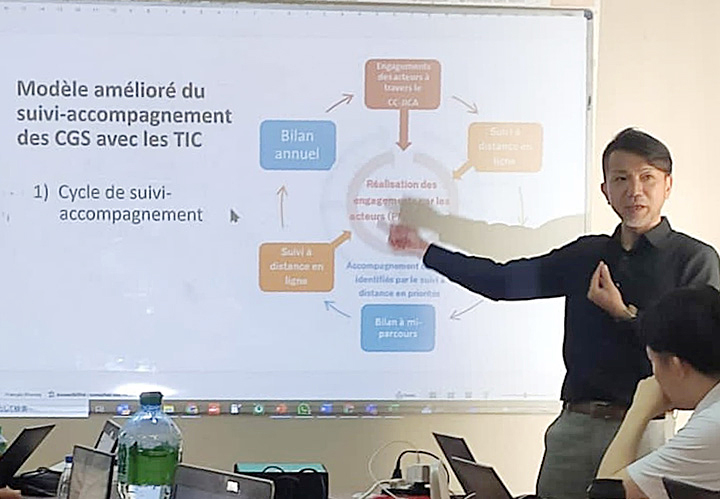

The first step in meeting this challenge was to use digital technologies. Fortunately, the share of people with internet access via their smartphones was rising rapidly in Bamako and surrounding regions. Efforts were thus made to maintain communication among stakeholders by conducting online surveys for monitoring purposes, offering remote training through streamed videos, and contacting education officials visiting schools in rural areas through chat groups. In addition, highly immersive virtual meetings were made possible thanks to video projectors with built-in, high-performance speakers provided by Seiko Epson. This enabled quality communication among officials of Mali’s Ministry of Education, local NGOs, and JICA experts in Senegal, on visits to other African countries, and in Japan. It also enhanced a sense of unity and mutual trust among project members.

Left: Parents responding to online surveys using their smartphones.

Right: Reports on the situation at various schools are sent by local representatives through a group chat.

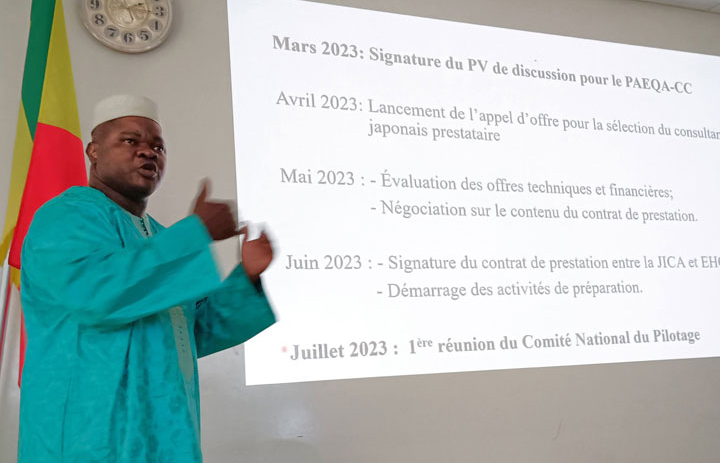

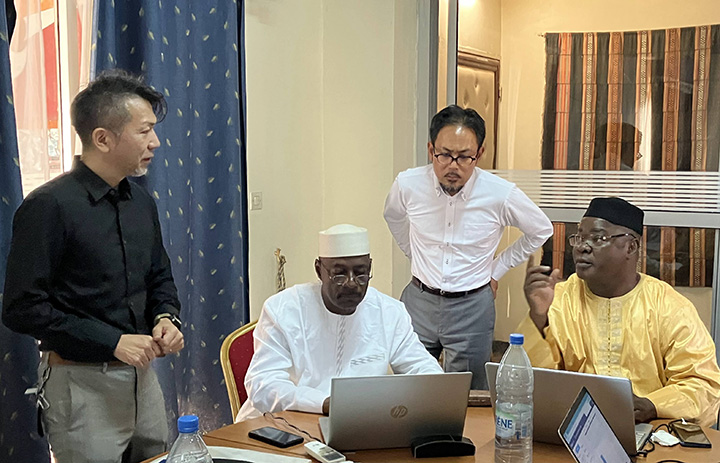

Iwata and his team also invited 21 members of Mali’s Ministry of Education and local NGOs to neighboring Senegal to discuss the plans, framework, and policies for the project; shared the key considerations and rules for remote implementation; and conducted training on the use of digital equipment. After the members returned to Mali, updates were shared regularly through weekly online meetings and daily exchanges of emails and chat messages. The key to sustaining these efforts, Iwata recalls, was the trust established with team members, notably Hassane Samassekou, head of the Support Unit for Deconcentration and Decentralization at the Ministry of Education.

“JICA’s technical cooperation is provided through a process that seeks alignment with the policies, culture, and customs of the partner country,” Iwata says. “We encourage our counterparts to develop the skills and capacity needed to solve their own challenges, thinking and learning with them and providing a helping hand when necessary. This means that hours or even days are usually needed to discuss the fine details of a project and reach a decision with which both parties are satisfied. Particularly with Mr. Samassekou, we came to trust each other deeply over the years of working together, developing a mutual understanding for each other’s personality, beliefs, work ethic, and our shared passion for education in Mali. We couldn’t have implemented this project remotely without such trust.”

“During my training in Japan,” Samassekou says of the cooperation with Japan, “I was deeply impressed on many occasions by the sincerity and dedication with which the Japanese people worked, and I felt that I understood why Japan became a highly developed country. Since we were going to have an opportunity to work with experts from such a country, I strongly urged everyone in my unit to watch how they worked and to learn from them. This led to a significant improvement in the overall performance of the unit. Thanks to the meticulous and detailed attention we received, there was never a time when we felt that the experts were far away, even though they were working remotely.”

Hassane Samassekou is a key figure in the project on the Malian side.

Iwata (left) and Samassekou (right) developed strong trust by fully discussing any issues that arose.

Political instability forced many changes to the project that required budget adjustments. So another vital factor in being able to advance the project remotely, Iwata notes, was the understanding and backing of JICA’s headquarters in Japan. “I’m truly proud of the staff there for the support shown for children in Mali and the trust toward those of us working in the field, despite being unable to see the local conditions and outcomes firsthand.”

The remote implementation of School for All can help ensure that learning opportunities for West African children are not lost due to political instability. In fact, Iwata believes that the project can not only improve the schooling environment and promote learning but also contribute to building peace in West Africa.

“The School for All project calls on community members to meet regularly, hold discussions to identify solutions, honor their commitment to act, and offer each other encouragement and congratulations on their achievements,” Iwata notes. “This process enhances the community’s ability to work together to resolve issues peacefully. And since this takes place at elementary schools across the country, what could be a more effective and sustainable means of peacebuilding? This is an initiative that can help lay the foundation for stable regional development. And I feel that the project was able to earn the trust and expectations of the officials and people of Mali because it was initiated by Japan.”

The opening passage of the UNESCO Constitution reads, “Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed.” Ever mindful of this goal of educational cooperation, Iwata continues to work alongside the people of Mali and other West African countries to realize a future in which children are assured of a safe learning environment.

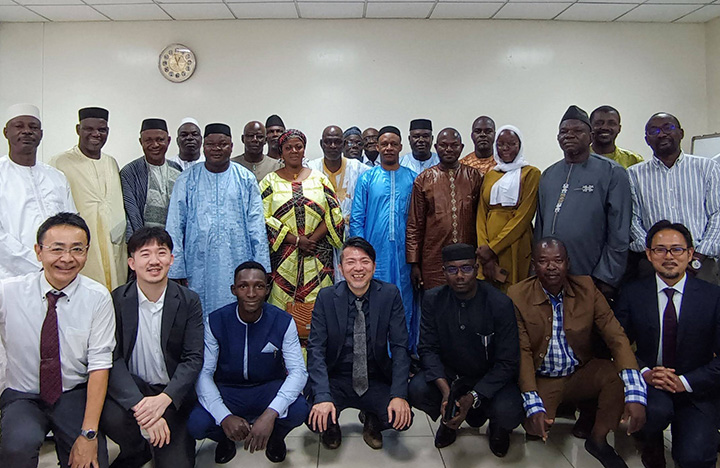

Members of Mali’s School for All project.

scroll