Building Peace with a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger: 80 Years After World War II

2025.08.28

In the summer of 2025, Japan marked 80 years since the end of World War II. While the country has maintained peace throughout the postwar era, conflicts have continued to increase around the world. What can we do to contribute to peace? Taguchi Seishiro, a first-year student at Seijo High School in Tokyo and a member of the 28th generation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messengers — a youth delegation that advocates for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the realization of a peaceful world — sat down with Oi Ayako, Senior Director of the Office for Peacebuilding at JICA, to discuss this question and other issues.

Oi Ayako, Senior Director of JICA's Office for Peacebuilding, left, and Taguchi Seishiro, a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger.

Oi Ayako, Senior Director of JICA's Office for Peacebuilding: Do you know how many conflicts are occurring worldwide?

Taguchi Seishiro: I've heard that about 20 new conflicts break out each year. Could you provide more insight into the actual situation?

Oi: According to figures from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, 61 state-based violent conflicts were confirmed worldwide last year. While Japan has been at peace over the 80 years since the end of World War II, during the same period, there has been no end to conflicts across the world, which have been increasing for nearly a decade.

Oi Ayako

Senior Director of JICA's Office for Peacebuilding. After working at a private television station, Oi was involved in supporting the return of internally displaced persons at the UNDP East Timor office and engaged in regional reconstruction at the Japanese Embassy in Afghanistan. After joining JICA, she worked in the Human Development Department, South Sudan Office and Africa Department. She served as Deputy Director of the Afghanistan Office before assuming her current position in January 2024.

Taguchi: I often see news about Ukraine and Palestine. During a school trip to Okinawa in junior high school, I learned about the Battle of Okinawa in the Pacific War, and just like in Okinawa's past, ordinary citizens are getting caught up in conflicts, which shocks me. Why do armed conflicts endlessly continue to break out like this?

Oi: The root causes of conflict often include discrimination or unfair treatment of specific ethnicities or groups. The inability of governments to provide essential services like education, health care and security to their citizens can also be a triggering factor. When people see no hope for the future and feel, "Why are we being treated so unfairly, why isn't our life improving?" it can lead to conflict.

Taguchi Seishiro

A 28th generation Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger. Born in Tokyo in 2010, Taguchi is a first-year student at Seijo High School. Selected as one of 24 individuals nationwide by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messengers Dispatch Committee in 2025, he is actively involved in a campaign to deliver to the United Nations the voices of those calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the realization of world peace. As part of the campaign, he is helping collect 10,000 signatures from Japan, the only country to have suffered atomic attacks. This campaign has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Taguchi: I've heard that JICA is involved in peacebuilding activities. What do these activities entail?

Oi: JICA operates in 145 countries and regions worldwide to address their needs. One area of cooperation is peacebuilding in countries affected by conflict. Taguchi-san, how would you define peace?

Taguchi: I suppose it would be a state without violence or fear.

Oi: That's right. However, even if there is no violence or fear, can we truly call it peace if people cannot express themselves freely or if there is a lack of education and employment opportunities?

Taguchi: I imagine such a situation would be unstable and would likely lead to conflict.

Oi: Exactly. JICA's peacebuilding activities are aimed at "building peaceful and just societies without fear and violence." We believe that the absence of fear and violence is not enough; the key point is ensuring a just society. For example, on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines, conflicts had continued between the government and Islamic groups in the Bangsamoro region since the 1960s before a peace agreement was finally reached in 2014. However, if citizens cannot live safely and securely, dissatisfaction may build up, causing violence to flare up again. JICA accordingly provides training to local government officials and works with them to form plans so that they can provide services such as in education, healthcare and employment corresponding to residents' needs. It also supports vocational training for former combatants to prevent them from resorting to use of force again due to unemployment.

A vocational training session is held on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines.

Taguchi: So it seems having a safe and secure life also contributes to reducing conflict.

Oi: I believe so. What do you think is important for peacebuilding?

Taguchi: I suppose a situation where people can tell each other what they feel from the bottom of their hearts and accept that. When I was in junior high school, I studied abroad in Australia. It was deeply fulfilling when I was able to connect with the locals. Even though my English wasn't fluent, when I tried my best to communicate through gestures, they also made an effort to understand me. I think the kind of dialogue that involves respecting and understanding each other is important for peace.

Oi: That aligns with JICA's approach to peacebuilding. Villages where conflicts have ended house diverse groups of people, from those whose family members were killed in the conflict to those who took part in the fighting and people who have returned from evacuation sites. Sometimes, former perpetrators and victims live next to each other. In such situations, we support community activities where residents can engage in dialogue with each other, and work together to produce and sell agricultural products for the reconstruction of the village after the conflict. We believe that building trust among people and between people and the government contributes to regional stability. We are undertaking such initiatives in places like Colombia in South America, where civil war has persisted for many years.

Farmers inspect the quality of cacao beans in Colombia.

Oi: Taguchi-san, what do you do as a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger?

Taguchi: We are gathering 10,000 signatures in support of nuclear abolition and world peace, which we will deliver to the United Nations Office at Geneva in Switzerland in September. We're working in the belief that as long as nuclear weapons exist, true peace of mind will remain out of reach. During our street campaign, more people than I expected stopped to listen, and we collected 137 signatures in just the first hour. People also encouraged us by saying, "Keep it up," and I feel a strong responsibility not to let their hopes go to waste.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger Taguchi Seishiro collects signatures in support of world peace and the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Oi: What inspired you to become a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger?

Taguchi: The direct reason was my teacher's suggestion to apply, but I was influenced by a documentary film I saw in my first year of junior high school. The film, "Mugen no Hitomi" (Infinite Eyes), was produced by the student council of Seijo High School in 1954. It documents how students started a fundraising campaign for a boy who was a hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor) and had developed leukemia, and how the support network expanded. I was deeply moved by the idea that if each person acts with conviction, a group can become a powerful force.

Oi: That's a wonderful story which I believe relates to your activities as a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger. What do you think can be done to encourage more young people in Japan to become more interested in world peace?

Taguchi: Some people around me are interested because I became a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger. Also, for those who love soccer, for example, taking an interest in the country of a player they support might serve as an entry point.

Oi: That's a very valuable insight. Speaking of soccer, there was a world-famous player named Drogba from Côte d'Ivoire in Africa. Amid a prolonged civil war in his homeland, the national team qualified for the 2005 World Cup in Germany. Drogba used that platform to call for an end to the war and for people to lay down their arms, and his message was delivered around the world. Soccer fans who didn't even know where Côte d'Ivoire was learned about the civil war through his appeal.

Taguchi: I believe experiences are important as well. In June, I visited Hiroshima for the first time for the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messengers' formation ceremony. Seeing a bomb-damaged lunch box and footage from that time at the Peace Memorial Museum and hearing directly from hibakusha have become the driving force behind my current activities.

Oi: Every time I visit Hiroshima, I feel a powerful message emanating from the entire city. JICA invites government officials from conflict-affected countries to Japan for training, which includes a visit to Hiroshima. The city of Hiroshima quickly rebuilt itself by listening to residents’ needs and developed a reconstruction plan. Those who come for training from countries affected by conflict see old footage of the city completely destroyed by the atomic bomb at the museum and relate it to their own countries. When they step outside and see how the city is now, it gives them a sense of hope seeing how far Japan has progressed in its post-war recovery.

Trainees visit Hiroshima Prefecture as part of a JICA program.

There are actually many things Japan can do for world peace. Over the past 80 years, Japan has built a peaceful society without war, though during major disasters like the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, many people lost their lives, families and homes, leading to evacuation and disruptions in education. We are seeing countries that have experienced conflict learning from Japan's experiences in post-disaster recovery, too.

Taguchi: Today, I learned many things I didn't know before. It gave me a renewed sense of how important it is for those of us in Japan to deliver a message of peace to the world.

Oi: Although there are many difficulties in peacebuilding, knowing that you are seriously thinking about peace from your own perspective gives me hope that if similar thoughts spread among the younger generation, the world will gradually move toward peace. The messages you convey through your activities as a Hiroshima and Nagasaki Peace Messenger will provide momentum for those who receive them to pass them on to the next person or take action themselves. I look forward to your continued efforts. JICA, including myself, will continue to work toward world peace.

JICA aims to create peaceful societies in developing countries that leave no one behind by helping to build resilient states and societies that can prevent outbreaks and recurrences of violent conflicts.

In Uganda, where there is a massive influx of refugees, building trust among the government, locals and refugees is crucial in alleviating tensions. JICA is working to improve livelihoods by enhancing the capabilities of local government officials and providing agricultural and other training for both refugees and members of the host community, to ensure that the needs of both groups are addressed after listening to their opinions.

Refugees learn rice cultivation techniques in rural Uganda.

In Palestine, JICA is supporting the creation of locally led improvement plans for refugee camps to improve the living conditions of refugees. In the planning process, women, who had had fewer opportunities to voice their opinions, were encouraged to participate in discussions, and through the implementation of vocational training for women and the establishment of childcare facilities, they gained confidence and began engaging more in measures to improve refugee camp environments.

Women wearing traditional embroidered clothing participate in an event aimed at intergenerational exchange and the preservation of traditional culture.

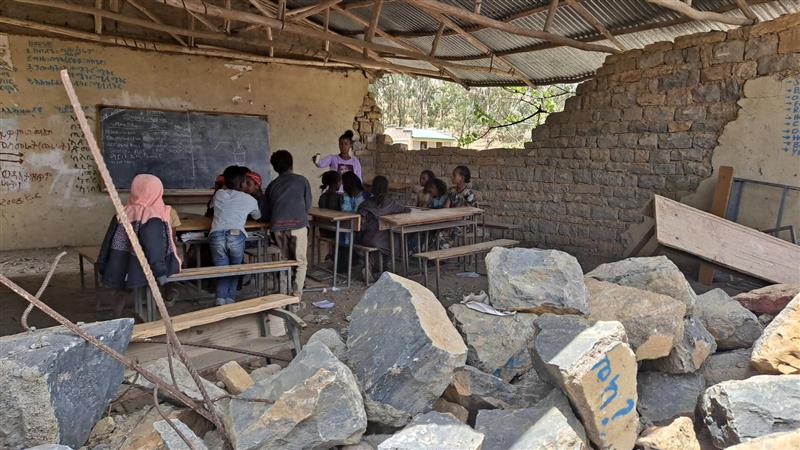

In northern Ethiopia, internal conflict continued for about two years before a peace agreement was achieved in 2022. In the post-conflict period, JICA has supported people's access to economic activities and education, taking into account the particular needs of vulnerable groups such as people displaced within the country, women and youth. By having government agencies collaborate with residents to provide services, JICA works to restore the trust between the government and residents.

A class resumes in a school building damaged by the Tigray conflict.

scroll