Blog Post | Africa's Transformation and TICAD 9: Can Japan Continue to Champion "Co-Creation"?

2025.12.18

Drawing on their diverse professional backgrounds, researchers at the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development (JICA Ogata Research Institute) bring a wealth of experience to the institute. They are actively building partnerships with a broad range of stakeholders. This blog series shares some of the insights and knowledge gained through their research activities. The present post was written by Akutsu Kentaro , Executive Senior Research Fellow, who has worked for development cooperation with Africa for a long time, including support for the TICAD process.

Author: Akutsu Kentaro, Executive Senior Research Fellow, JICA Ogata Research Institute

“I didn’t come here to teach. I came here to learn.”

Quoting these words of Noguchi Hideyo, who had pursued yellow fever research in Ghana around 100 years ago, Japan’s Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru addressed African leaders on 20 August 2025 at the opening ceremony

of the Ninth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD 9)

, held in Yokohama, Japan. The theme of TICAD 9—“Co-create innovative solutions with Africa”—echoed Noguchi’s spirit of learning from Africa while seeking solutions together, a stance that symbolically reflects Japan’s approach.

Since its inception in 1993, TICAD has convened nine times, and this latest summit unfolded amid a dramatically changing global context for Africa.

Professor Endo Mitsugi of the University of Tokyo has described the current state of international relations in Africa as characterized by “thin hegemony” and a “thin liberal order,” meaning no single power can exert overwhelming influence (see Gaiko [Diplomacy] No. 91, among others). Following the establishment of the second Trump administration, U.S. engagement with Africa—and, by extension, that of European nations—has become even "thinner."

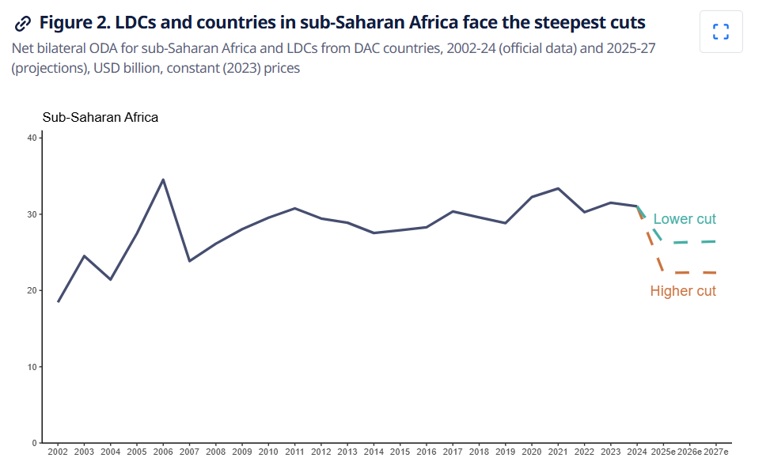

The impact on development cooperation, particularly Official Development Assistance (ODA), has been severe. Since February 2025, over 80% of U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) projects have been suspended, and by July, the agency was dismantled altogether. Given USAID’s extensive role in the health sector, a July article in The Lancet projected that this disruption could increase mortality risk for 14 million people globally over the next five years, with Africa bearing the brunt of the consequences. In Europe, the UK announced in February a reduction in its ODA budget—from 0.5% to 0.3% of Gross National Income (GNI)—citing increased defense spending due to the protracted war in Ukraine. Germany, France, and Switzerland have similarly implemented or planned cuts. According to an OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) report released in June , total ODA from DAC donors in 2025 is expected to decline by 9–17% year-on-year, with aid to Sub-Saharan Africa projected to fall by 16–28%, reaching its lowest level in two decades.

Trends and Projections of ODA from all DAC donors to Sub-Saharan Africa

(Source) https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/cuts-in-official-development-assistance_8c530629-en/full-report.html

Trade relations have also deteriorated. In April 2025, the U.S. imposed reciprocal tariffs, including a record-high 50% rate on Lesotho (later reduced to 15% in August), and many African countries now face tariffs exceeding 15%. The expiration of the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) in September ended the preferential zero-tariff regime that many African nations had long enjoyed.

While Western engagement has “thinned,” China announced in May 2025 that it would eliminate tariffs on imports from African countries and reportedly offered expanded assistance to some nations following USAID’s dissolution. Russia, too, has strengthened its influence in regions such as the Sahel, supplanting France, and at the BRICS summit in October 2024, introduced a “partner country” framework following earlier membership expansion to include Egypt and Ethiopia. Uganda and Nigeria were designated as partner countries in January 2025.

Meanwhile, African economies remain resilient. According to the African Development Bank (AfDB)’s African Economic Outlook (May 2025), average growth is projected at 3.9% for 2025 (with 21 countries exceeding 5.0%) and 4.0% for 2026, despite downward revisions due to U.S. tariff policies. Demographically, Africa’s population is expected to account for 20% of the global total by 2030 and 25% by 2050 (UN estimates ), positioning the continent as a central market in the global economy.

However, challenges persist: recurrent droughts and floods linked to climate change, rapid urbanization, soaring youth populations (median age: 19), and mounting employment insecurity. Conflicts continue in regions such as the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. In short, global fragmentation and indifference cast a shadow over Africa, making the search for solutions to its complex social challenges an urgent priority.

The current situation—where Western engagement with Africa has “thinned”—echoes the early 1990s, when Japan launched TICAD. Professor Shirato Keiichi of Ritsumeikan University details this history in an oral account of senior officials at Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (see Foresight ). Following the end of the Cold War, Western ODA to Africa plummeted, as its previous strategic rationale—countering the Eastern bloc—had disappeared. Against this backdrop, and in conjunction with South Africa’s dismantling of apartheid under President de Klerk, Japan sought to lift sanctions and strengthen cooperation with Africa. In 1991, Japan announced the TICAD concept, and the first conference was held in 1993 .

Since then, TICAD has convened every five years in Japan, and since 2016, alternately in Africa and Japan every three years. From the outset, TICAD emphasized African “ownership” and international “partnership,” creating an inclusive, multi-stakeholder framework involving international organizations, partner countries, private firms, and NGOs. Over time, TICAD has incorporated key policy agendas: “Human Security” (from TICAD III ), “From Aid to Investment” (from TICAD V ), and “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP, from TICAD VI ). The author himself has been directly or indirectly engaged in the TICAD process since TICAD IV in 2008.

Today, numerous “Africa+1” summits exist—China, Korea, India, Indonesia, Iran, Turkey, Latin America, Russia, Italy, Germany, France, the UK, the EU, and the U.S.—as noted by Professor Endo (op. cit.). Yet TICAD remains distinctive: it was among the earliest forums to rekindle global interest in Africa when others were disengaging; it is multilateral rather than bilateral, co-hosted by Japan, the United Nations (UN), UN Development Programme (UNDP), the World Bank, and the African Union Commission (AUC); it includes partner countries (for triangular cooperation) and private sector actors; and it features a robust follow-up mechanism through ministerial meetings. These characteristics continue to define TICAD’s strength.

Against the backdrop of shifting global dynamics and TICAD’s historical role, what made TICAD 9 meaningful? Held from 20 to 22 August in Yokohama (with thematic events before and after), TICAD 9 brought together all 49 African countries eligible to participate (excluding five AU-suspended states), including 33 heads of state or government. Beyond the plenary sessions, more than 200 thematic events for public audience, including those where African and Japanese leaders and ministers jointly attended; JICA alone hosted 44 sessions, attracting roughly 10,000 participants on-site and online. A business expo by JETRO showcased 194 companies and organizations, drawing another 10,000 attendees, and 324 partnership agreements were signed among governments, private firms, NGOs, and international organizations—making this the largest TICAD ever. The author also participated in bilateral meetings and events on-site during the period, and personally felt the bustle was significantly greater than at past TICAD summits.

While its scale was impressive, TICAD 9’s qualitative significance can be summarized in four key dimensions:

First, TICAD 9 demonstrated Japan’s unwavering—and even strengthened—commitment to Africa at a time when Western engagement is receding. By convening a summit that actively involved the UN, the World Bank, and other international actors, Japan signaled the enduring importance of international cooperation over isolationist tendencies. In an era marked by fragmentation, polarization, and indifference, the very act of hosting TICAD 9 carried profound symbolic weight.

Second, as reflected in the theme “Co-create innovative solutions,” TICAD 9 advanced the previous shift from “aid to investment” toward “investment for problem-solving.” This means promoting business as a means to address social challenges, with public sector playing a supportive role.

Given the complexity of Africa’s social issues and inevitable reductions in Western ODA budgets, the private sector—not governments—must take the lead. By enabling businesses to help solve social problems while generating growth, TICAD 9 clarified Japan’s strategy to circulate Africa’s growth and Japan’s economy and develop jointly.

Among the initiatives proposed by the Japanese government at TICAD 9, the Economic Region Initiative of Indian Ocean-Africa , i.e. so-called the “new Economic Region Initiative”, likely garnered the most attention. It can be said to embody this concept succinctly. Although the Japanese government first proposed FOIP (Free and Open Indo-Pacific) at TICAD VI (2016) held in Kenya, discussions on FOIP, including within the QUAD (Japan-Australia-India-U.S.) framework, often focused on ASEAN and the Pacific region east of India.

Diplomatically, the new Economic Region Initiative appears to reposition FOIP to be more inclusive, encompassing all of Africa. However, within the context of the aforementioned "co-creation of innovative solutions," Japanese companies are already working with businesses and governments in Indian Ocean nations (i.e. India and Middle Eastern countries) and African nations to address Africa's social challenges through business.

In terms of Japan's balance of payments, Japanese companies already generate more revenue from overseas investment than from trade, and they reinvest those profits abroad.

The Japanese government and other governments would support this through enhanced connectivity within and beyond the region and cooperation among like-minded nations. This concept represents the "co-creation" of diverse actors.

Third, as a foundation supporting the second dimension mentioned earlier, TICAD 9 highlighted Japan's new development cooperation, expanding the horizons of ODA.

Chronologically, this coincided with the revision of Japan's "Development Cooperation Charter" in 2023 , the year following the previous TICAD 8. This revision explicitly added "solidarity" with various actors as a pillar of "human security " for a new era, alongside the existing pillars of "protection" and "empowerment," aimed at resolving the world's complex crises. Therefore, "co-creation" with developing countries is crucial. To strategically achieve this, "Co-creation for Common Agenda Initiative " was introduced, where Japan proactively proposes initiatives to developing countries. Furthermore, in April 2025, reflecting the principles of the revised Charter, amendments to the Japan International Cooperation Agency Act (JICA Act) were enacted , establishing institutional reforms to promote private sector financing mobilization through ODA.

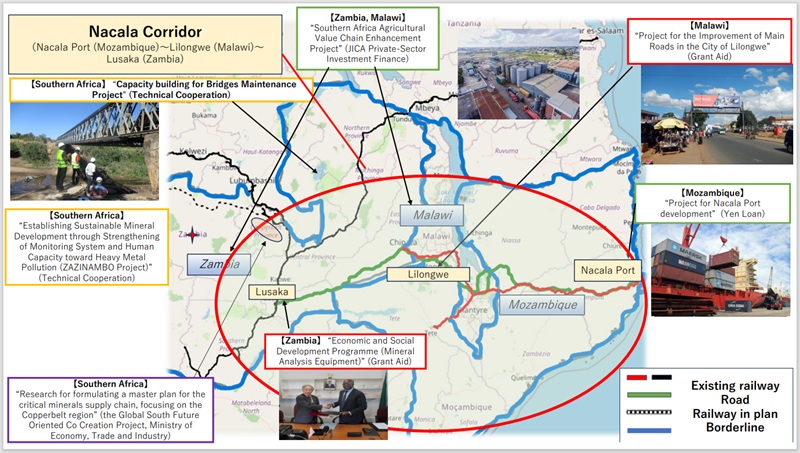

At TICAD 9, it was essentially required to embody the outcomes of this series of ODA reforms (to borrow the words of a senior Foreign Ministry official, "Paradoxically, ODA reforms have been advanced with TICAD 9 in mind."). Responding to these policy demands, several noteworthy new ODA programs were announced to address social challenges in Africa. Both are included in the aforementioned new Economic Region Initiative. One is the region-wide co-creation for common agenda initiative for Mozambique, Malawi and Zambia: “Strengthening the Global Supply Chain through Nacala Corridor Development.” The other is the co-creation for common agenda initiative for Nigeria: “Solution of social challenges and building economic resilience by supporting startups.”

The former provides ODA support in resource-rich Southern Africa, linking the high-value-added processing and environmental considerations desired by African nations for their mineral resources with Japan's economic security (securing mineral resources). This is combined with strengthening international corridors as global supply chains (enhancing connectivity), premised on "co-creation" between Japanese and African companies. Japan’s new Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae also referenced this initiative in her speech at the G20 Johannesburg Summit in November.

Region-wide co-creation for common agenda initiative for Mozambique, Malawi and Zambia: “Strengthening the Global Supply Chain through Nacala Corridor Development”

(Source) https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100891375.pdf

The latter involves supporting startup development to address social challenges in Nigeria, one of Africa's most populous and largest economy. It includes a new initiative using ODA as a catalyst for private funding (the first example of "Grant Aid for Private Sector Mobilization").

Beyond the new Economic Region Initiative, IDEA (Impact Investing for Development of Emerging Africa), newly incorporated into the Enhanced Private Sector Assistance for Africa (EPSA) Initiative through collaboration with the AfDB , aims to fundamentally strengthen JICA’s Private Sector Investment Finance (i.e. non-sovereign loan aid) for Africa. This includes initiatives such as coordinating with the AfDB to provide subordinated fund investments for private capital mobilization, made possible by the aforementioned revision of the JICA Act. This initiative is also drawing significant attention.

Finally, as another significant step toward "co-creating innovative solutions," TICAD 9 formally hosted "Youth TICAD " for the first time, featuring African and Japanese youth. This marked the debut of youth as partners in "co-creation" at TICAD. The policy proposal "Youth Agenda 2055 ," compiled through six months of online and offline discussions by over 900 young people from Africa and Japan, was submitted to the TICAD Plenary Session.

Youth TICAD representatives Ms. Yasumiba and Mr. Kpondehou present the policy proposal "Youth Agenda 2055" to the Parliamentary Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Ms. Eri. (Photo: JICA)

The proposal focuses not only on the three discussion areas of TICAD—"Society," "Economy," and "Peace and Governance"—but also highlights "People-to-People Relationships" and "Sustainability" as enablers and cross-cutting elements. David Kpondehou, the African representative, and Yasumiba Yuki, the Japanese representative of Youth TICAD, attended the TICAD 9 closing ceremony with African and Japanese leaders. In his speech, Japan’s then-Prime Minister Ishiba specifically called for action, demonstrating a commitment to youth.

Beyond Youth TICAD, TICAD 9 also expanded its horizons through the "ABCD+Y TICAD" initiative. This added A (Academia), C (Culture), and Y (Youth) to the traditional D (Development) and B (Business) emphasized in past TICADs. Notably, C-TICAD featured thematic events in areas previously underrepresented at TICAD, such as diversity (disability mainstreaming), art, cultural heritage, and music, attracting diverse participants including the younger generation.

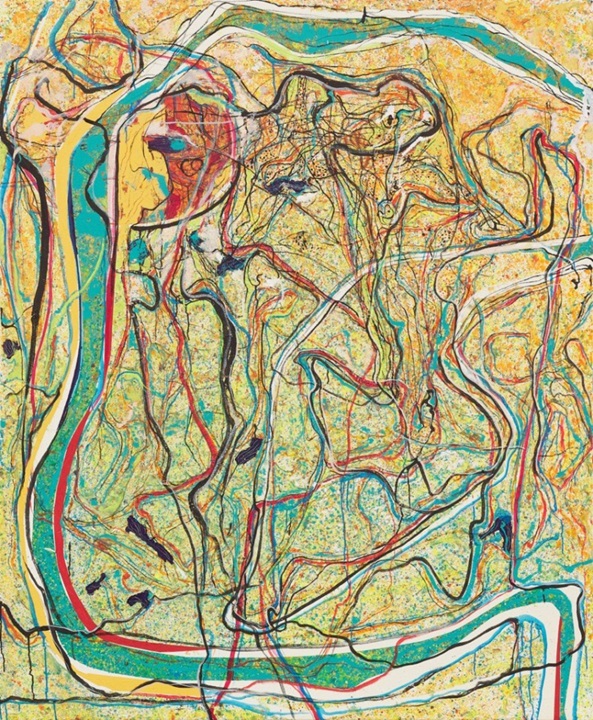

Speakers at the Diversity (Disability Mainstreaming, Art) Thematic Event.

Center: Ethiopian artist Mr. Tesfaye Bekele Beli (Photo: JICA)

Tesfaye's work "Balance of Movement." A finalist in the 2024 Art Prize by Japanese startup HERALBONY

, which promotes art by people with disabilities. Adopted as JICA's TICAD 9 key visual.

(Source) https://ticad9event.jica.go.jp/

Amid deepening divisions, conflicts, and apathy, engaging people beyond existing international cooperation and Africa-focused circles in the TICAD process has become an even more critical issue than before. Continuing such efforts is highly desirable.

“Japan must not fall behind in the race for Africa’s growing markets.” — Karube Jun, Chair of the Committee on Africa, Keidanren (Gaiko [Diplomacy] No. 91)

“Competition over the African market will inevitably intensify. Japanese firms should pay attention to the cost of inaction.” — Ide Tatsuya, Chair of the Middle East and Africa Relations Committee, Japan Association of Corporate Executives (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 03 August 2025)

As TICAD 9 demonstrated, the agenda has shifted from aid to investment—and now toward co-creating solutions. The expectation is clear: the private sector, not governments, will lead this transformation.

Both business leaders quoted above underscore the urgency for Japanese companies to seriously consider entering African markets. By TICAD 10 in 2028, we hope to see many more Japanese firms actively engaged in Africa, shaping discussions on-site.

Finally, let me close with a message from a Youth TICAD member to the senior generation:

“In a world—and even in Japan—where divisions and conflicts are deepening, young people often hesitate to raise their voices. We hope the senior generation will lead by example, transcending divides and continuing to champion co-creation with Africa.”

Akutsu Kentaro

After holding several managerial positions in JICA and the Government of Japan, he assumed his current role in 2025. His main research interests include Africa area studies, human security, peacebuilding and governance.

*This blog post is based on content contributed by the author in Japanese to issue No. 93 of the magazine Gaiko [Diplomacy] (published October 2025) produced by JIJI Press Publication Service, with permission from the Service. It has been reconstituted in English, supplementing content, figures, and photographs that had to be omitted due to space constraints in the original Japanese version.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s and do not reflect the opinions of JICA or the JICA Ogata Research Institute.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.