JICA Ogata Research Institute Experts Deliver the 2020 Peacebuilding Intensive Course at the Graduate School of International Development, Nagoya University

2020.08.31

Aug. 24 to 27, 2020, Rui Saraiva, a research fellow at the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development (JICA Ogata Research Institute), was invited as a visiting lecturer to teach an intensive peacebuilding course at the Graduate School of International Development (GSID), Nagoya University. The course offered an introduction to peacebuilding theory and delved into how international peacebuilders today explore new pathways for peace in an increasingly complex world. Saraiva invited his colleague Muto Ako, an executive senior research fellow from the Institute, to teach a session on peacebuilding and human security from JICA’s perspective.

Research fellow Rui Saraiva (top center) gives a lecture to the master's students of Nagoya University

Armed conflicts are becoming longer and recur more often, frequently involving various nonstate and external state actors. In recent years, the numbers of armed conflicts, refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and civilian casualties have increased. As there is new demand for more effective peacebuilding, the lectures provided the students with innovative techniques to examine the various pathways for preventing and resolving armed conflicts. These are skills valued by international organizations such as the United Nations, bilateral development agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) working in the field of peacebuilding.

Saraiva introduced Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung’s conceptual framework, which links peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding. It also addresses the dichotomy between “negative peace,” i.e., the absence of physical violence, and “positive peace,” the attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies. He noted that, traditionally, peacebuilders seek to understand the causes and drivers of conflict and how to fix them, but the insights from the United Nations Sustaining Peace Agenda suggest a renewed focus on promoting “positive peace,” which is much more complex than the mere absence of war. The students were encouraged to complement standard conflict analysis approaches by identifying the complexity dimension of conflict-affected societies and what is already working in society and could be strengthened.

The second part of Saraiva’s lectures examined local ownership issues, i.e., the degree of control that domestic actors wield over the peacebuilding process. Other topics included the humanitarian-development-peace nexus, and its call to change working modalities to respond to a rapidly evolving operational landscape, and the differences between determined-designed theoretical approaches, e.g., liberal peacebuilding, and context-specific approaches, such as bottom-up peacebuilding, hybrid peacebuilding and adaptive peacebuilding. Considering the global study on the implementation of U.N. Security Council resolutions 1325 and 2250, the lectures included a discussion on the roles of women and youth in peacebuilding, which are essential for gender and age perspectives in peace and security issues.

The course counted with the active participation of six master’s students of GSID, Nagoya University. Based on the conflict analysis models and peacebuilding theories introduced by Saraiva’s lectures, the students further developed their research and applied their academic knowledge to various case studies. Students presented their analyses, including on the internal conflicts that escalated in Georgia and their relation to the emergence of ethno-nationalism and the ethnic security dilemma; the potential of women peacebuilders in Libya through the Libyan National Conference Process; the Mindanao Peace Process, and how JICA has supported various multi-sector development needs in the conflict-affected areas of Mindanao, the Philippines; the Syrian conflict and its complexity as a main obstacle to the peace process, and the role of NGOs and community-based organizations (CBOs) in Syria’s peace infrastructure; peacemaking and humanitarian support in Yemen; and the ongoing insurgency in Thailand’s Deep South and related peace initiatives, including a recent cease-fire during the COVID-19 crisis.

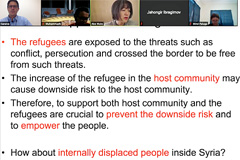

Muto Ako of the JICA Ogata Research Institute gave a lecture on human security and JICA. Muto started by underlining that human security includes concerns about human freedoms from want and fear, and dignity and survival, and recognizes that vulnerable groups and sources of threats are an essential focus of the human security policy framework. Given that threats can originate from institutions (e.g., the economy, health or the environment) or systems (e.g., physical or social systems), human security requires a people-centered, context-specific and prevention-oriented approach that aims at protection and empowerment. In this line, she observed that Japan’s human security approach places significant attention on people’s protection and empowerment.

Muto Ako, an executive senior research fellow, gives a lecture on human security and JICA

She also explained that JICA’s perspectives on human security combine top-down and bottom-up approaches and aim to provide cross-sectoral aid while promoting partnerships with multiple actors and managing down-side risks. As an example, she cited JICA’s work with Syrian refugees in Jordan supporting both the host and refugee communities, through educational programs, awareness-raising, youth activities, financial aid, infrastructure rehabilitation and assistance to improve services at the Village Health Center. She indicated that JICA’s significant interventions in Jordan collectively assisted the protection and empowerment of the Syrian refugees while also preventing host communities’ down-side risk, and that a combination of bottom-up and top-down methods seems to facilitate the validation of multiple actors involved in both human security and peacebuilding. As human security aims also focus on inclusiveness and equitable human development, it directly contributes to addressing structural and systemic violence, she said. She concluded her lecture by saying that human security enables the recognition of local and complex dynamics of communities affected by conflict and contributes to positive peace and sustainable development.

The broad understanding of human security discussed in Muto’s lecture allowed Nagoya University students to think deeper about the close connections between security, peace and development.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.