Interview With Director General Miyahara Chie: Maintaining Perspectives From the Field With Her Passion for the Middle East

2023.10.17

Miyahara Chie was appointed as director general of the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development (JICA Ogata Research Institute) in April 2023. We asked her about her involvement with the Middle East, an area she has focused on for many years, her thoughts on peacebuilding, and future tasks she would like to accomplish at the JICA Ogata Research Institute.

—What originally got you interested in development cooperation?

It all started when I got interested in the Middle East during my childhood. I loved world history so much that I wanted to join archaeological excavations when I grow up. Through TV programs and books, I gradually came to know the richness of the history and geopolitics of the Middle East and went on to study Arabic at university. I even studied in Egypt for a while. After returning to Japan, I first joined a private company but then made the big decision to become an international civil servant so that I could work in the Middle East and around the world. I went to an American graduate school to study public administration. This was the first time for me to look at the Middle East and developing countries as the site of development. For me, it started from the question, “How would I be able to work in the Middle East?”

The graduate school I went to had an internship agreement with the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) program, which sends volunteers from around the world to contribute to assisting developing countries and humanitarian aids in conflict areas. Through this, I got to work at the UNV Cyprus Office after graduation. While working there, I passed the Junior Professional Officer (JPO) exam held by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan and was then sent to the Humanitarian Relief Unit of UNV in Geneva, Switzerland, as a JPO.

—Why did you choose to work at JICA after working at a UN agency?

First, UNV’s main role is to send volunteers to various UN agencies. I wanted to do more in planning and managing entire projects so I was not fully satisfied. Second, there was the dilemma of expectations you are exposed to as a Japanese staff member of the UN. I thought that things may get simpler if I become a Japan-based Japanese working at a Japanese organization. Back then, Japan was a major donor country, so I thought there would be things I could do even if I was not part of the UN. JICA was sharing Japan’s insight with partner countries within the big picture: giving financial assistance, dispatching experts, providing equipment and drawing up master plans after conducting studies. I wanted to participate in JICA’s activities which addressed development assistance in an integrated manner.

—You worked in various departments at JICA. Please share about your most memorable work.

In my third year at JICA, I was assigned to the Department of Planning and Evaluation (which has been reorganized since then). I worked on issues that were new to JICA at the time like population issues, HIV/AIDS, gender issues, assistance for people with disabilities, and peacebuilding. Being a development cooperation agency, JICA was hardly active in fields that are directly involved with peacebuilding operations when I joined JICA in 1999. However, when the Official Development Assistance (ODA) Charter was revised in 2003, Japan’s contribution to peacebuilding was more clearly mentioned. Following this, JICA started to consider how it could contribute to peacebuilding and what should be done for safety management in implementing peacebuilding activities, and drew up the guiding principles that underlie JICA’s activities. I remember that my horizons were broadened through this experience.

—You were also assigned twice to the JICA Jordan Office in the Middle East, your childhood dreamland.

Around 2005, when I was first assigned there, the economic growth of Jordan was at its height. More foreign investments were coming in, the stock market was going strong, the economy was booming and I had a strong feeling that most of the people there were happy. However, when I was assigned there for the second time in 2019, this time as the chief representative of the Jordan Office, the situation was very different. The unemployment rate was high especially among younger generations, what with the civil war in neighboring Syria and the global economic downturn, droughts were occurring because of climate change, and foreign investments were slowing down due to increased electricity costs. Of course, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic followed. I have experienced two completely different Jordans.

Nevertheless, some things had not changed: experts from Japan continued to jump into circles of Jordanian people and devoted themselves to activities on the ground while engaging in heated discussions. One example is Sato Tokiko, an expert on maternal and child health (currently the vice president of Nagoya University of Foreign Studies), who made every effort to improve reproductive health in southern Jordan over more than a decade. This is a region where local traditional practices are strictly observed but Sato improved understanding on female empowerment and made the idea of reproductive health take root by even getting the involvement of local men, including traditional local leaders. This project itself has already ended but the achievements are known so widely that officials of the Ministry of Health of Jordan still recognize the name “Doctor Sato” today.

When there was an influx of refugees to northern Jordan because of the Syrian conflict, JICA implemented a project that covered reproductive health in northern Jordan based on the maternal and child health work that was successful in the south. Furthermore, as water resources are scarce in Jordan, JICA has supported the installation of water transmission and distribution pipelines with grant aids over the years. As the knowledge and experience were already embedded, when the influx of Syrian refugees to northern Jordan raised concerns of water shortage, JICA was able to quickly start the installation of distribution pipelines. As seen in this case, trust built through the activities in Jordan over the years has led to swift emergency support. I believe that this was indeed the moment JICA’s resourcefulness shone.

Sato worked over the years to improve reproductive health in southern Jordan (Photo: JICA/ Kuno Shinichi)

—What do you think the strengths and roles of the JICA Ogata Research Institute are?

All in all, as JICA implements various development projects on the ground, the JICA Ogata Research Institute has a lot to study. The activities in various projects at its core, from which data are acquired and analyzed to be fed back into projects, give the institute great strength. Meanwhile, there are many big challenges and topics that need to be discussed globally like the post-2030 agenda and carbon neutrality. JICA Ogata Research Institute has the capacity to digest discussions on these and pass on the results to various departments at JICA and their stakeholders. The people who are capable of utilizing research outcome exist within JICA and I think this is a huge strength of the JICA Ogata Research Institute.

—Where do you want to put effort from here? Please share your ambitions with us.

Human security and the post-2030 agenda would be some of our key research themes for years to come. I would also like our institute to focus more on the field. By utilizing our advanced analysis results, we would like to feed back our findings into development cooperation projects in the field, rather than just publishing them to be kept tucked away in bookshelves. As I have worked in the field for many years, I would like to engage in all activities without leaving out this perspective.

I personally think that research on human security in the Middle East would be interesting. As many countries in the region are absolute monarchies, the term “security” is often linked with national security and ends up becoming political talks. With this in mind, how may the idea of human security be accepted in the Middle East? How does this region look like through the perspective of human security? I am interested in its characteristics.

—We can feel your unchanged great passion in the Middle East.

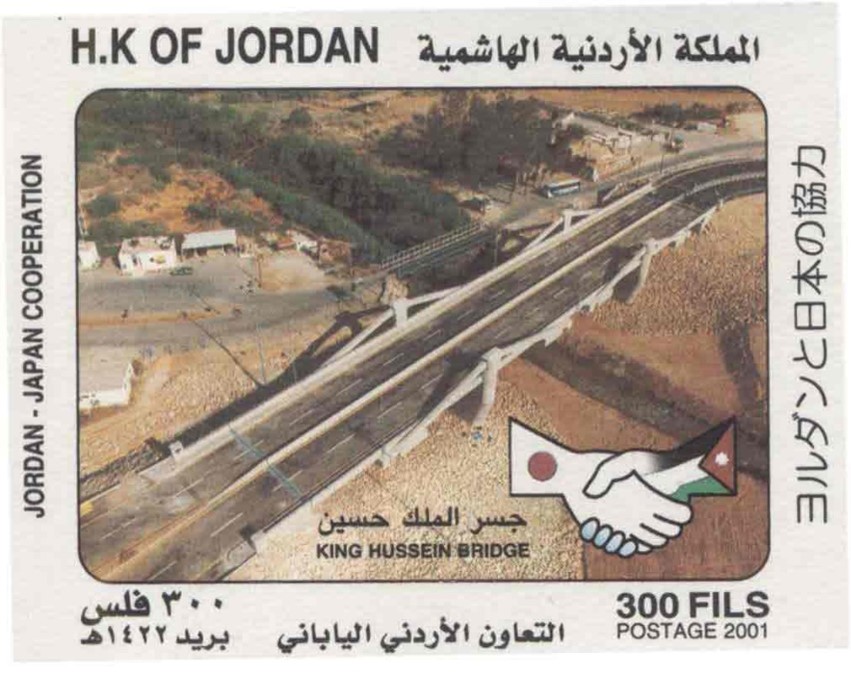

I think the Middle East continues to be at my core. In 1989, when I was studying in Egypt, I visited Israel via Amman, Jordan, as a backpacker. Back then, we had to cross an old bridge over the Jordan River to enter Israel and I can never forget the bucolic atmosphere. Years later, I was posted in Jordan as a JICA officer and saw a new bridge over the Jordan River that was built with the grant aid from Japan. On countless occasions I have crossed the new bridge, from which the old bridge is still visible. From the 1990s to today, peacemaking in the Middle East has gone through ups and downs but still struggles to progress. It is as if I am witnessing this reality with my own eyes. I would like to continue to do my best in contributing to this region, so that the situation improves.

A commemorative stamp that was issued in 2001 in Jordan to honor the friendship between Jordan and Japan. It shows the King Hussein Bridge. (Photo: JICA)

King Hussein Bridge across the Jordan River(Photo: JICA)

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

scroll