Blog “Food Security and Agricultural Development in Light of Africa’s Development” (3): Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women in Rural Areas

2025.03.07

Researchers at the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development (JICA Ogata Research Institute) have wide-ranging experience and diverse backgrounds, and they are forging partnerships with varied stakeholders and partners. This series of blog posts shares the knowledge and perspectives that they have acquired through their research activities. This blog post was written by Amameishi Shinjiro, Executive Senior Research Fellow, who is working on research on agricultural development in Africa.

(Photo: JICA)

Author: Amameishi Shinjiro, Executive Senior Research Fellow, JICA Ogata Research Institute

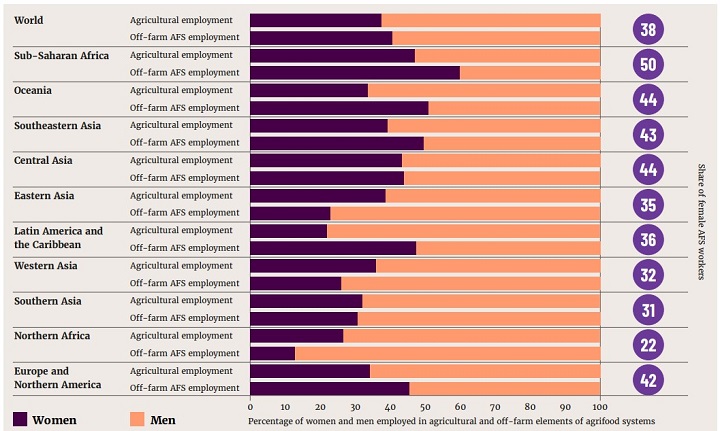

There are longstanding challenges around food security and agricultural development in Africa. There are calls for active and equal participation of rural women in agrifood systems (AFSs) in Africa. More than half of the African female working population (53.2% as of 2021) is in the agricultural sector (ILO Regional Office for Africa 2020) and although this sector tends to be perceived as being male dominated, the significance of the roles of women is a key feature of African agriculture. Africa has the world’s highest female employment rate of 50% in agricultural and off-farm jobs in AFSs* (Fig. 1). To lead the soon-expected drastic increase in working population to a healthy economic development, active and equal participation of rural women in AFSs will be necessary in Africa.

Fig. 1: Female employment rate in agricultural and off-farm jobs in agrifood systems (AFSs) around the world

Source: FAO (2023)

*See “Sub-Saharan Africa” (SSA) in Fig. 1. For both agricultural employment and off-farm AFS employment, SSA has the greatest percentage of women in AFSs in the world.

Rural women play important roles in all parts of food systems, as farmers, processors, paid workers, traders or consumers. To transform food systems, gender equality and the empowerment of rural women are essential (UN Food Systems Coordination Hub 2023). However, efforts to achieve these are significantly delayed in Africa. The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP), which is being led by the African Union (AU) for over two decades, sets forth efforts to facilitate the participation of women in agribusiness, but the score that indicates their progress level** is 2.23 out of 10 (a score of 9.00 is seen as the benchmark for being “on track”), and there is a significant delay in progress (AU and AUDA-NEPAD 2024).

In agricultural production activities in Africa, women play important roles in physically demanding farmwork like soil preparation, sowing, planting, cultivation management and harvesting. However, the productivity of female farmers falls far behind that of male farmers. The gender gap is said to be 4–40% (Djurfeldt et al. 2018) or 4–28% (Puskur et al. 2023). Factors creating this gender gap in productivity include restrictions around landownership (such as unequal landownership systems or rights), low usage of agricultural inputs (such as chemical fertilizers, improved seeds and pesticides) and limited access to services for technology dissemination and agricultural financial services that female farmers face. If these restrictions are removed, their agricultural productivity has the potential to reach the same level as that of male farmers (Mukasa et al. 2016, Adebayo et al. 2024). Furthermore, compared to male farmers, female farmers are more vulnerable to shocks and stresses caused by climate change and natural disasters, with their livelihoods more significantly affected by these (FAO 2023). This is again due to women having less options for adaptation compared to men, as they have less access to necessary resources such as land, time, workforce, information and technology. Gender inequality in agricultural production needs to be overcome from the perspectives of human security and food security. Rural women are in charge of many household chores at home such as cooking, child rearing, water collection and firewood collection to begin with, and the workload of female farmers particularly exceeds that of male farmers (Adebayo et al. 2024). To unlock the full potential of rural women, gender equality awareness needs to be instilled within both households and agricultural production communities.

African rural women suffer a loss within agricultural value chains as well. As they are not involved much in shipping, marketing and sales — the most profitable stages in agricultural value chains after produce is sent out to local markets — rural women are not profiting enough. Issues around accessibility to technology and information, low levels of education attained, issues around their assets and networks, and low levels of responsibility given within communities, have been pointed out as the factors contributing to the limited involvement of rural women in agricultural value chains (Ola 2020, Abadeyo et al. 2024). By removing gender-based barriers to the participation of rural women, it is anticipated that not only agricultural production but also agribusinesses will be stimulated, and each stage in a wide range of value chains will be vitalized.

The Smallholder Horticulture Empowerment and Promotion (SHEP) approach is an effort by JICA with a gender perspective. Focusing on small-scale farmers, the SHEP approach has two pillars: i) promoting farming as a business; and ii) empowering farmers and boosting their motivation. 256,546 small-scale farmers in 30 African countries have benefited from this effort to date (Kitajima 2024). The SHEP approach is characterized by how farmers themselves take the initiative to study their own farming-business operations and market situations. Based on the results, they decide which crops to produce, cultivation timing and sales channels. Gender mainstreaming is another key area for SHEP. Since 2015, the JICA Ogata Research Institute has been working on research on the SHEP approach

. Shimizutani et al. (2021)

showed that in Kenya, the horticultural income of SHEP farmers has increased by an average of 70% in two years. The increase was significant in vulnerable farming families headed by women, those with a low-educational background or elderly people and was not affected by prior market experience. Nomura et al. (2024)

suggested that in Ethiopia, by gender equality training offered through the SHEP Project, joint decision making between husband and wife in married couples is encouraged in each household, and this kind of decision making may increase horticultural income. The SHEP approach facilitates the exertion of initiative and capacity among small-scale farmers and is contributing to nurturing “proactive farmers.” The positive impact of this from a gender perspective has been shown academically as well.

Recently, there is increased awareness on the importance of female empowerment and system reforms not exclusive to gender equality. Empowerment must be addressed not only to allow rural women to have equal opportunities as men but also to enable them to truly shine. First, efforts to increase the influence, roles and leadership of women at all levels (household, community and AFS) must be moved forward (Njuki et al. 2022) but for continued change, not only do gender gaps need to be resolved but structural restrictions that create inequality should be removed as well. Awareness on handling structural barriers that cause deep-rooted inequality that exists informally (e.g., gender norms), formally (e.g., restrictions, laws and policies) and semi-formally (e.g., statistics and data systems), is on the rise (McDougall et al. 2023).

The most important thing is to tenaciously continue our efforts and produce outcomes so that we can approach many rural women. However, in African agricultural development, structural and restrictive social norms that prevent women from playing active roles must be addressed in order to be able to build a society where women can fully utilize their capacities. Efforts that put more priority in gender equality and female empowerment in agriculture need to be made by the AU, African governments and development partners including JICA.

**In the reviews by CAADP, progress is evaluated on a scale of 1 to 10 for each element. The benchmark score for being “on track” depends on each element and is revised per review.

Adebayo, Johnson A. and Steven H. Worth. 2024. “Profile of women in African agriculture and access to extension services” Social Science and Humanity Open. 9(2024)

African Union (AU) and African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD). 2024.

4th CAADP Biennial Review Report 2015-2023.

Djurfeldt, Agnes Andersson, Fred Mawunyo Dzanku and Aida Cuthbert Isinika, 2018. “Agriculture, Diversification, and Gender in Rural Africa”.

FAO.2022.

Statistical Yearbook World Food and Agriculture 2022

FAO. 2023.

The Status of Women in Agrofood Systems

Kitajima, Harue. 2024. “Introduction of Smallholder Horticulture Empowerment and Promotion (SHEP) Approach as an Innovative Agricultural Extension Model” African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. Volume 24. No 3.

ILO Regional Office for Africa. 2020.

Report on Employment in Africa 2020

McDougall, Cynthia, Marlène Elias, Desiree Zwanck, Karen Diop, Johana Simao, Alessandra Galiè, Gundula Fischer, Humphrey Jumba and Dina Najjar. 2023. “Fostering gender-transformative change for equality in food systems: a review of methods and strategies at multiple levels” CGIAR GENDER Impact Platform · Working Paper #015

Mukasa, Adamon N. and Adeleke O. Salami. 2016. “Gender equality in agriculture: What are really the benefits for sub-Saharan Africa?” African Development bank (AfDB) Africa Economic Brief. AEB Volume7 Issue 3.

Njuki, Jemimah, Sarah Eissler, Hazel Malapit, Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Elizabeth Bryan and Agnes Quisumbing. 2022. “A review of evidence on gender equality, women’s empowerment, and food systems” Global Food Security 33 (2022) 100622

Ola, Kehinde Oluwpole. 2020. “Micro-determinants of women’s participation in agricultural value chain: Evidence from rural households in Nigeria”.

Puskur, Ranjitha, Humphrey Jumba, Bhim Reddy, Catherine Ragasa, Linda Etale, Steven Cole, Anvi Mishra, Margaret Najjingo Mangheni and Eileen Nchanji. 2023. “Closing Gender Gaps in Productivity to Advance Gender Equality and Womens Empowerment”. CGIAR Gender Impact Platformm Working Paper #14

Shimizutani,Satoshi, Shimpei Taguchi, Eiji Yamada and Hiroyuki Yamada. 2021. “The Impact of “Grow to Sell” Agricultural Extension on Smallholder Horticulture Farmers: Evidence from a Market-Oriented Approach in Kenya” Keio-IES Discussion Paper Series. Institute for Economic Studies, Keio University.

United Nations Food Systems Collaboration Hub. 2023.

Synthesis Report of the Regional Preparatory Meetings for the UN Food Systems Summit +2 Stocktaking Moment

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s and do not reflect opinions of JICA or the JICA Ogata Research Institute.

Amameishi Shinjiro

Amameishi is an Executive Senior Research Fellow at the JICA Ogata Research Institute since 2023. He joined JICA in 1994 and after serving as a Project Expert (Laos), he worked at the following: the Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); Rural Development Department, JICA; JICA Tanzania Office; JICA Kenya Office; and the Economic Development Department, JICA. Amameishi’s main research areas include agricultural development, agricultural policy, participatory development and aid coordination in Africa.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

scroll