Interview With Visiting Fellow Teguh Dartanto: Vision for Indonesia’s School Lunch Program

2026.01.30

In July 2025, Teguh Dartanto joined the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development (JICA Ogata Research Institute) as a visiting fellow. He is currently conducting research at the Institute, and in this conversation he discusses his vision for Indonesia’s emerging school lunch program and reflects on the work he has undertaken over the years—including his research on the so-called “middle-class crisis.”

—Welcome back to the JICA Ogata Research Institute, Dr. Teguh. How does it feel to return after 10 years?

It feels like coming home. Over the past decade, I have served as a lecturer and researcher at Universitas Indonesia and later as the Dean of the Faculty of Economics and Business (2021–2025), where I helped to guide academic transformation through challenging times, including the pandemic. After completing my deanship in June 2025, I wanted to step away from administration and refocus on research—so returning here as a visiting fellow is both nostalgic and refreshing, and a welcome opportunity to reengage with my research interests.

—What first brought you to Japan?

I arrived in 2005 under a government scholarship, earning my master’s at Hitotsubashi University and my PhD at Nagoya University, where I shifted my academic focus from fiscal decentralization to poverty and inequality studies. Later, I joined the JICA Research Institute [which changed its name to the JICA Ogata Research Institute in 2020] as a research associate, contributing to projects on poverty dynamics and publishing two Working Papers (No. 54 and No. 117 ). My years in Japan shaped my academic and leadership approach, instilling a strong emphasis on perseverance and teamwork. These experiences also deepened my long-term research collaboration with JICA and recognition from the Ambassador of Japan to Indonesia.

—You are now researching Indonesia’s school lunch program at the Institute. What is the program about, and what challenges does it face?

Indonesia’s Free Nutritious Meal Program (Makan Bergizi Gratis, MBG), launched in 2025, aims to provide free nutritious meals to all children from preschool to high school, as well as toddlers and pregnant women. Its goals are ambitious: to reduce stunting, improve learning outcomes, and ultimately support poverty reduction.

President Prabowo introduced MBG as a universal program during his campaign, aiming to integrate and expand existing targeted schemes into a single nationwide initiative. This represents a bold shift—from previous fragmented, small-scale interventions —such as PMT-AS (Supplementary Feeding for School Children), PROGAS (Additional Food Program for School Children) and PMT Ibu Hamil dan Balita (Supplementary Feeding for Pregnant Women and Toddlers)—to a unified, nationwide model of nutritional support. While the intention of a nationwide initiative is admirable, national socioeconomic data consistently show that nutrition problems are heavily concentrated among the bottom 40 percent of households, which raises important questions: Should Indonesia prioritize universal coverage or would a more targeted approach direct resources more equitably toward those most in need? How can a universal approach be balanced with effective targeting and long-term fiscal sustainability?

Fiscal sustainability is another concern—the program could cost as much as Rp. 400-450 trillion annually, equivalent to over 13% of the national budget.

Operational challenges are equally daunting: the program will need to ensure safe and consistent delivery across thousands of islands, maintain food quality, and prevent waste. For toddlers and pregnant women, who are among the most vulnerable to malnutrition, meals will be distributed through community platforms like Posyandu and Puskesmas or prepared in local kitchens rather than schools. Designing a safe, efficient, and scalable mechanism for these groups remains a key operational challenge.

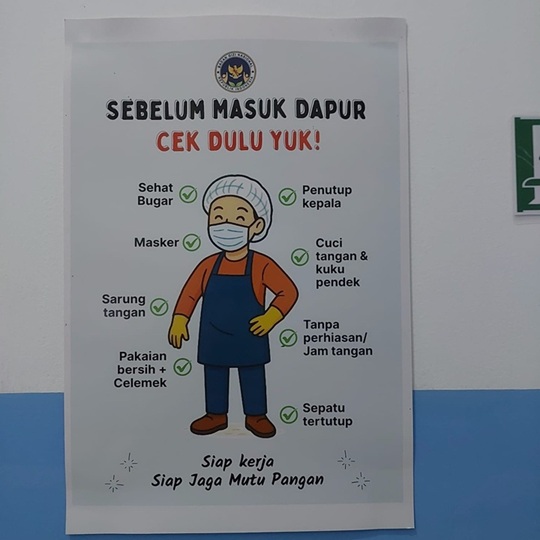

Various hygiene reminders are posted in the school kitchen for the safe provision of school meals

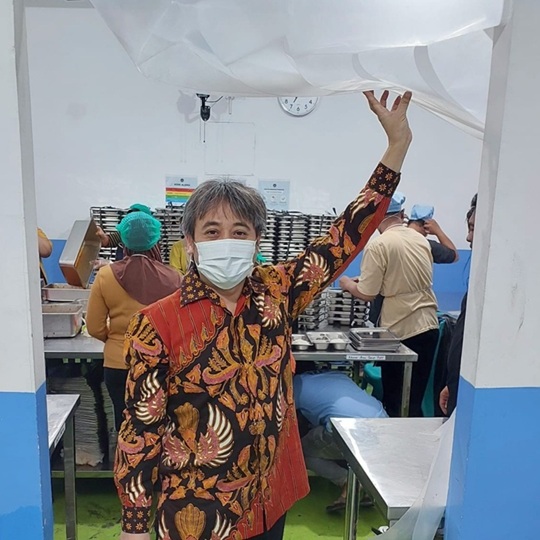

School lunch prepared and packed at a kitchen

Physical stunting remains severe, affecting 21–22% of Indonesian children, with lasting effects on their health, education, and earnings. At the macro level, the long-term impacts of this reduce GDP by 2–3 percent, making nutrition improvement an economic imperative as well as a health priority. My research will assess its fiscal feasibility through simulation models and analyze broader economic effects—on GDP, employment, poverty, and inequality—using the input–output and microsimulation approaches. The goal is to guide policymakers toward a model that is inclusive, resilient, and financially sustainable, ensuring the program strengthens human capital and supports long-term prosperity.

Kitchen staff preparing school lunches

Dartanto visiting a kitchen where school meals are prepared

—What aspects of Japan’s experience regarding school lunch programs might be applicable to Indonesia?

Japan’s experience offers valuable insights. Its school lunch program began in 1889 in Yamagata Prefecture. What started as a small-scale effort has steadily evolved— especially after World War II, following the enactment of the School Lunch Act in 1954. Since then, the program has grown nationwide and transformed from simply “feeding students” into a holistic approach to nutrition education known as shokuiku . It was especially meaningful for me to participate in JICA’s group training course, School Health and Nutrition, in Mie Prefecture from October 13 to 16 this year, which gathered participants from 12 countries. The exchange not only deepened my understanding of Japan’s approach but also allowed me to compare how different countries approach child nutrition.

During the training, I visited two schools—one in a rural area and another in a more urban setting. Although both shared the same national principles, their approaches reflected their local contexts. I was particularly impressed by how systematic and disciplined the food preparation process was, from cooking in the school kitchen to serving and eating together. What stood out most was that the shokuiku program

goes far beyond providing meals. It teaches students cooperation, appreciation for food, and awareness of nutrition and health through direct participation. In that sense, the school lunch truly becomes a “living classroom.”

From Japan’s experience, several key lessons could be meaningful for Indonesia. The first is to pursue gradual implementation, expanding step by step while remaining responsive to local contexts. The second is to ensure fiscal sustainability through cost-sharing among the central government, local authorities, and parents. The third is to leverage a decentralized system, allowing local schools to design menus and source ingredients that reflect local culture. The fourth is to combine on-site and centralized kitchens, ensuring both efficiency and food safety. Finally, the fifth is to integrate lunch with education, teaching respect for food, producers, and the environment—showing how Indonesia’s Free Nutritious Meal Program could evolve into a platform that not only feeds children but also nurtures healthier habits among future generations.

—Aside from your research on school lunch, you are well known for introducing the concept of the “middle-class crisis.” What does this term mean?

I have studied Indonesia’s middle class for eight years, building on my earlier work at the JICA Research Institute on poverty dynamics, which was published as Working Paper No. 117 . In that study, using five waves of the Indonesia Family Life Survey, we found that between 1993 and 2014, poverty declined dramatically—from 86 percent to about 20 percent—while the middle class expanded almost ninefold. About a third of the poor successfully moved into the middle class. This transition inspired me to believe that Indonesia’s future development will increasingly be shaped by the strength and resilience of its middle class. We later published these findings in the Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies in 2020. But our research also revealed a concern: many households are now stagnating, unable to move beyond the middle class. In a way, it mirrors the “middle-income trap” that we often discuss at the national level—only now are we observing a similar pattern at the household level.

After that, my team began exploring the issue from multiple dimensions—how to measure it properly, how it relates to political participation, and how economic mobility interacts with health and wellbeing. In 2023, together with my co-authors, I published an article related to Indonesia’s middle class, showing that the welfare of the middle class actually declined between 2019 and 2023. The growth-incidence curve we used was simple but powerful, sparking a national debate. Our institute (Institute for Economic and Social Research, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia; LPEM FEB UI) later released a 2024 report confirming this downward trend, and official statistics soon followed—showing a loss of around 9.5 million people from the middle class. What began as a technical observation has turned the “middle-class crisis” into a key area in Indonesia’s economic policy discussions.

For me, the key message is clear: a strong and expanding middle class is essential to Indonesia’s prosperity. The middle class drives consumption, innovation, productivity, and democratic stability. If we want to achieve Indonesia Emas 2045—Indonesia’s vision for achieving its development goals by 2045—we need policies that make the middle class more resilient, inclusive, and forward-looking, because they are not just beneficiaries of growth; they are the backbone of it. I am now expanding this line of research to compare middle-class dynamics across ASEAN countries and identify lessons Indonesia can learn from its neighbours.

—Your research spans health, poverty, inequality, and the middle class. What is your overarching academic goal?

Although my research areas may seem diverse, they share one underlying theme: human capital development. Development is multidimensional, and progress depends on building people’s capabilities. Whether I am studying Indonesia’s Free Nutritious Meal Program or the country’s current middle-class crisis, I am ultimately asking: how do we enable people to live better, more productive, and more secure lives?

Over the past years, our research using 21 years of longitudinal data has shown that the strongest drivers of poor households moving into the middle class—or even higher—are education and health investments. These two elements consistently shape mobility and long-term resilience. That’s also why I am so interested in the MBG program. It’s not only a nutrition intervention; it’s a direct investment in human capital, especially for children from low-income families. Good nutrition strengthens cognitive development and learning, which, in turn, can later influence and support greater economic mobility.

My overarching academic goal is to generate evidence that helps Indonesia and other developing countries design policies that strengthen human capital from early childhood through adulthood. Ultimately, I want my work to support a development path that is more inclusive, more equitable, and truly centered on people’s well-being—because strong human capital is the foundation for a strong middle class and a prosperous nation. Thank you.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

scroll