Blog “Considering Infrastructure Development Cooperation in Developing Countries”

2024.12.20

Researchers at the JICA Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development (JICA Ogata Research Institute) have wide-ranging experience and diverse backgrounds, and they are forging partnerships with varied stakeholders and partners. This series of blog posts shares the knowledge and perspectives they have acquired through their research activities. This blog post was written by Endo Kei, who is participating in research projects on infrastructure development.

Source: Final Report on the Bang Sue Smart City development in Thailand

Author: Endo Kei, Research Fellow, JICA Ogata Research Institute

Do you know that with official development assistance (ODA), Japan provides financial and technical cooperation to develop infrastructure such as transportation networks and water-supply and sewerage systems in developing countries? This may not be new to you if you are working in developing countries or are interested in international relations. However, perhaps many of you are new to this or may not be familiar with the details even if you have heard about it before. As a matter of fact, as of 2009, only 29.4% of the Japanese people were aware of ODA loans, which are mainly used for large-scale infrastructure development (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan [MOFA], 2009). Although my current work looks at infrastructure development and assistance to carry it out in developing countries, I myself was not aware that Japan assists infrastructure development in developing countries until I saw railways and airports constructed with Japanese ODA during a trip around Southeast Asia as a student.

In this blog post, based on my hands-on experience and research, I would like to provide an overview of Japan’s cooperation with developing countries to develop infrastructure, along with some new trends in recent years. I would also like to share some next-step research topics.

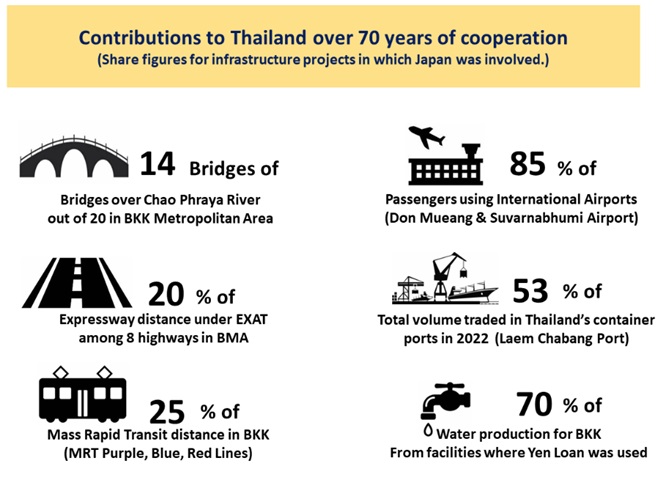

From the World War II reparations in the 1950s to today, infrastructure development cooperation remains a core pillar of the Japanese ODA. A significant amount of infrastructure development cooperation has taken place to date, mainly in Asia. Let us see some actual figures. Between fiscal years 1966 and 2018, Japanese ODA loans (yen loans) amounted to 13.3 trillion yen for 988 projects in total, for transportation infrastructure such as roads, rails and ports. During this same period, for electricity and gas infrastructure, ODA loans amounted to 7.71 trillion yen for 696 projects in total (Yamada, 2021). These numbers may be too large for grasping the scale of things so let us turn to figures by country. In the case of Thailand, for example, Japanese ODA has helped constructing 70% of the water-supply and sewerage systems and 25% of the mass rapid transit (MRT) system in Bangkok (Fig. 1). In Indonesia, 60% of the Trans-Sumatra Toll Road and toll roads in the Jakarta metropolitan area (including segments where Japanese ODA was used for designing and planning only) and power plants covering 20% of the country’s total generation capacity were constructed by Japanese ODA (JICA, 2018). Infrastructure development cooperation by Japan is widely recognized by the governments and the people of developing countries; infrastructure projects by Japanese ODA have been depicted in postage stamps and coins in many countries.

Fig. 1: Percentage of infrastructure development projects in Thailand that received assistance from Japan (as of 2024)

Source: Website of the Embassy of Japan in Thailand (Figure retrieved on May 28, 2024.)

Through infrastructure development cooperation, Japan has earned a great reputation and gained trust from the governments and the people of the recipient countries. Although it is natural for recipients to express their gratitude as ODA is a form of assistance, it is worth noting that for instance, at the ceremony to start lowering the tunnel boring machine for the Metro Manila Subway Project (June 12, 2022), Rodrigo Duterte, President of the Philippines at the time, expressed how highly he regards infrastructure development cooperation by Japan. In his speech, he said “I cannot seem to fathom the love of the Japanese people for this republic…Japan has continued to help us to the extent that iyong ibang -- pati ng (even) Davao City, the new highway and the bridge and everything…We are the -- you know, being treated as almost a part of Japan…“ (Philippine News Agency). On another note, according to the Opinion Poll on Japan in FY 2023 by MOFA, 84% of respondents from ASEAN countries answered that Japan has an “important role” in development cooperation in the global community (including ODA). 91% of the same respondents answered that Japan is “reliable.” Of course, their trust in Japan must be related to multiple factors such as economic or security relations with Japan as well as their resonance with the Japanese culture. Yet still, development cooperation by Japan, including infrastructure development cooperation, is thought to be also contributing to trust building to a certain extent.

That said, this does not mean that the infrastructure development cooperation by Japan has had no issues. In its long history, Japan’s ODA and its projects were criticized at times, by the aid recipient countries, from within Japan or by the global community. For instance, in the 1970s, tied aid, which limited procurement sources of materials and equipment to Japanese companies, was criticized by the global community. In the 1980s and the 1990s, issues like pollution and forced migration that were caused by Japanese ODA projects (infrastructure projects in particular) led to criticism from the locals in the project areas, aid recipient countries, Japanese media and non-governmental organizations (NGO). Yet infrastructure development cooperation managed to remain a core part of Japanese ODA, because those involved responded with sincerity to criticism from time to time and addressed the issues to make improvements. In the case of the issue of tied aids, yen-loan tied aids were scaled down from the late 1970s and have been monitored by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) since then. As for pollution and forced migration, environmental guidelines to be applied to ODA projects were formulated in 1990, and in 2004, these were revised to formulate the JICA Guidelines for Environmental and Social Considerations. Since then, the guidelines have been regularly expanded with the participation of academia and NGOs (Harashima, 2022). This series of processes involving criticism and improvement over the years did not just lead to quality improvement of ODA infrastructure projects based on extrinsic motivations. Rather, as explained later, I believe that it led to where Japan’s infrastructure development cooperation is in recent years, willingly improving the quality of infrastructure development cooperation in response to the trend of the times.

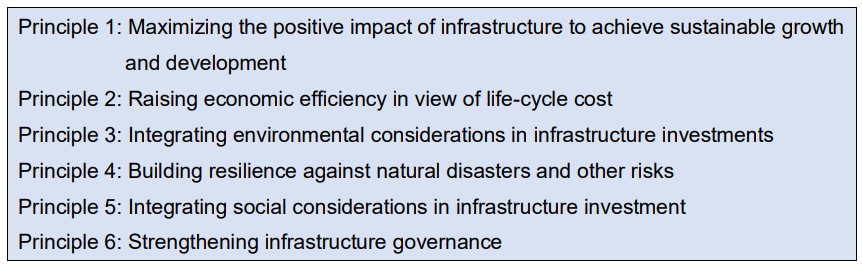

In recent years, infrastructure development cooperation by Japan is increasingly prioritizing the quality of the infrastructure. The increase in the amount of aid is another feature seen recently as there are more ODA infrastructure mega-projects, including those for the construction of subway rail systems or ports. There is an emphasis on the quality of infrastructure in all projects. The G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment,

proposed by Japan and internationally approved at the G7 Ise-Shima Summit 2016 and G20 Osaka Summit 2019, are symbolic. These consist of six principles (Fig. 2) but roughly speaking, investment in infrastructure with high quality from three aspects—economic, environmental and social—is defined as “quality infrastructure investment.” Quality infrastructure investment is a globally well-known concept in the field of development and international organizations like the World Bank and OECD promote it as well. Furthermore, the development of “quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure” is covered in Target 9.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were set out by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the UN in 2015. Quality infrastructure investment was accepted by the global community as it matches the philosophy of the SDGs to push sustainability forward from every aspect.

Fig. 2: The G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment

*Made by the author based on the G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment.

The true background behind the proposal of the concept of quality infrastructure investment is not clear. However, it is generally thought among scholars of international politics that quality infrastructure investment was conceived as a countermeasure against infrastructure investment by China in developing countries which became active in the first half of the 2010s. China launched the Belt and Road Initiative, a strategy to build a mega trade bloc through infrastructure development in 2013 and then led the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2015. Japan is thought to have proposed quality infrastructure investment as an economic and political countermeasure. (See Sasada, 2019, and Yoshimatsu, 2017.) Furthermore, around this time, bidding competition between Japan and China became fierce for a few infrastructure projects such as the Indonesian high-speed rail project and the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High Speed Rail (KL-SG HSR). Many political scientists link quality infrastructure investment and its great driving force, ODA, not only to conventional international development and commerce (infrastructure exportation) but also to geopolitics. (See Jain, 2019, Zhao, 2019, Murashkin, 2018, and Liao & Katada, 2021.)

Japan proposed the concept of quality infrastructure investment and successfully allowed it to take root internationally. The factors that enabled this have not been discussed much academically but are important when thinking about the evolution of development cooperation by Japan. Japan was able to set this concept out and push it forward because the foundation to establish norms for infrastructure development that focus on topics attracting global interest like the SDGs and environmental and social considerations was already there. This was perhaps because Japan, with a great deal of experience going through processes involving criticism and improvement, was already highly aware of topics attracting global interest, and actively explored ways to realize better infrastructure development cooperation through continued trial and error. To give an example, as mentioned earlier, a mechanism to reinforce the JICA Guidelines for Environmental and Social Considerations through revisions was already in place. In response to criticism of Japanese ODA in the past, a mechanism for post-project evaluation in accordance with DAC standards and monitoring, which includes the perspectives of accountability and the application of lessons learned (i.e., making improvements) was already there as well. Another reason is perhaps that Japan won the trust of the aid recipient countries where ODA projects are being implemented as attentive assistance that empathizes with developing countries, encouraged by such active improvements of infrastructure development cooperation (Shinrai to Kaihatsu Kyoryoku Kenkyu-kai [Study Group on Trust and Development Cooperation], 2023).

On another note, the emphasis of quality in infrastructure development cooperation is a good thing for developing countries and their people. Indeed, infrastructure development cooperation by Japan in recent years emphasizes the quality of infrastructure; from the perspective of how to maximize the effect of development beyond simple assistance for infrastructure construction, various types of technical cooperation are being provided. For example, in developing countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam, Japanese ODA provides assistance to transit-oriented development (TOD). That is, projects to construct railway systems do not just lay railroad tracks or build train stations but rather, are centered around public transportation, carrying out integrated development of areas and facilities along railroad lines and near railway stations. (See Knowledge Forum “How Can Japan Contribute to Quality Infrastructure Investment in Developing Countries? Learning from Cases of ODA in Urban Transportation” for details.) Another example is the National Road No. 5 Improvement Project in Cambodia. This project does not just repair and expand roads but also provides technical cooperation to improve road safety. Moreover, when evaluating ODA projects including infrastructure development projects, a revised set of evaluation criteria with new perspectives added based on the SDGs, which are “leaving no one behind” and “well-being of the people,” are applied. As such, infrastructure development cooperation by Japan based on the concept of quality infrastructure investment, which emphasizes enhanced quality from all aspects—economic, environmental and social—is thought to be capable of significantly contributing to the sustainable development of developing countries.

Now you can see that quality infrastructure investment is a concept that contributes to sustainable infrastructure development in developing countries. What topics need further academic analysis and research then? I believe there are two important ones.

The first is the consideration of whether it is actually good to maximize quality from all three aspects: economic, environmental and social. This topic tends to be overlooked as the majority of developing agencies around the world are currently working equally on quality improvement from all three of these aspects when conducting infrastructure development. However, this topic will be important in future norm-building for infrastructure development. It is important from an academic perspective as well, because depending on each scholar, the level of focus differs between the three aspects in infrastructure development (Endo et al., 2023).

This topic is also relevant to the definition of sustainability, which remains debatable in the field of environmental economics. The interpretation of “sustainability” is largely divided in two: some take the approach of “strong sustainability,” that is, they think that natural capital must be maintained and protected; meanwhile, others take the approach of “weak sustainability,” that is, they think that natural capital can be replaced by manufactured capital (Neumayer, 2003). Infrastructure development that aims to comprehensively maximize value created from the three aspects (economic, environmental and social) can be seen as a concept inclined to weak sustainability, because it may come at the cost of the environment when there are tradeoffs between each aspect. However, considering how global interest in the environmental aspect is growing recently, infrastructure development that takes a strong-sustainability approach (such as by prioritizing biodiversity conservation) may be possible.

Alternatively, some may think that the people who benefit from the infrastructure should be prioritized (i.e., having emphasis on the social aspect) because infrastructure means nothing if no one benefits from them. Indeed, some studies have pointed out that social sustainability was not sufficiently considered and addressed in infrastructure projects, not only in developing countries but also in developed countries. (See Hueskes et al., 2017, and Robles & Gaspay, 2024, for example.) However, we must avoid focusing on just one of these three aspects and neglecting the other two. I believe that from now onward, while looking at all three aspects, to what degree it is acceptable for each aspect to be expanded or reduced must be thoroughly considered in order to find the right balance.

The second topic, which is relevant to the first topic, is to consider whether infrastructure development that maximizes quality from all three aspects is actually possible. Studies on sustainability often discuss the tradeoffs between the three aspects (economic, environmental and social) and how to manage them. (See Morrison-Saunders & Pope, 2013, and Gibson, 2006, for instance.) When we look at the SDGs, which make up a key framework for sustainability in recent years, many scholars have pointed out that tradeoffs and synergetic effects exist between different targets. (One example is Kroll et al., 2019.) Therefore, when economic, environmental and social aspects are all considered for infrastructure development, naturally, there is a possibility that issues involving tradeoffs between them exist. For example, a report on a water-supply infrastructure project in Ghana says that economic efficiency was excessively prioritized in this project and those in poverty were unable to fully benefit from it (Egan & Agyemang, 2019). Meanwhile, generally speaking, the cost to construct infrastructure that prioritizes the environment or convenience tends to be large and this may lower economic efficiency (at least in the short run).

In order to address these topics and realize optimum infrastructure development for developing countries and the people who live there, I think that the following kinds of research will become crucial in the social sciences. First, we need to accurately understand how much impact is exerted on economic, environmental and social aspects when infrastructure projects are implemented. With this, we can get important information for considering how infrastructure development with a good balance of these aspects may look like. This can be done comprehensively when findings from research work as seen in “Empirical research on the social and economic impacts of infrastructure projects,” an ongoing project by the JICA Ogata Research Institute, are accumulated. Second, which aspect can be expanded or reduced to what degree without any problem must be analyzed by studying actual projects. To contribute to this, I am currently conducting research on the Jakarta MRT project. Of the various services and fares of the Jakarta MRT, I am trying to understand which ones are the factors that most significantly affect customer satisfaction. Third, the development of frameworks and analytical tools needed to plan a well-balanced infrastructure project is needed. In development cooperation practice, an international certification framework for quality infrastructure and sustainable infrastructure called the Blue Dot Network (BDN) is currently being established. I think that academia can contribute to the establishment of this framework or other similar frameworks.

This blog post has provided an overview of Japan’s cooperation with developing countries to develop infrastructure, along with some new trends in recent years. I have also shared some next-step research topics. I hope it has sparked interest among readers in Japan’s cooperation with developing countries to develop infrastructure.

Egan M., and Agyemang G. “Progress towards sustainable urban water management in Ghana.” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 10(2): 235-259, 2019.

Endo, K., Edelenbos, J., and Gianoli, A. “Sustainable infrastructure: a systematic literature review on finance arrangements and governance modes.” Public Works Management & Policy, 28(4): 443-475, 2023.

Gibson, R. B. “Beyond the pillars: sustainability assessment as a framework for effective integration of social, economic and ecological considerations in significant decision-making.” Journal of environmental assessment policy and management, 8(03): 259-280, 2006.

Hueskes, M., Verhoest, K., and Block, T. “Governing public–private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects.” International journal of project management, 35(6): 1184-1195, 2017.

Jain, P. “Japan’s Foreign Aid and ‘Quality’ Infrastructure Projects: The Case of the Bullet Train in India.” JICA-RI Working Paper No.184, 2019.

Kroll, C., Warchold, A., and Pradhan, P. “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies?.” Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 2019.

Liao, J. C. and S. N. Katada. “Geoeconomics, easy money, and political opportunism: the perils under China and Japan’s high-speed rail competition.” Contemporary Politics. 27(1): 1-22, 2021.

Morrison-Saunders, A., & Pope, J. “Conceptualising and managing trade-offs in sustainability assessment.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 38: 54-63, 2013.

Murashkin, N. “Not-so-new Silk Roads: Japan’s Foreign Policies on Asian Connectivity Infrastructure Under the Radar.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 72 (5): 455–472, 2018.

Neumayer, E. “Weak versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms.” Edward Elgar, 2003.

Robles, L.R., and S.M. Gaspay. “Examining Women’s Commuting Experience in Urban Philippines: A Photovoice Exercise on Human Security.” JICA Ogata Research Institute Discussion Paper No.20, 2024.

Sasada, H. “Resurgence of the “Japan Model”? Japan’s Aid Policy Reform and Infrastructure Development Assistance.” Asian Survey 59 (6): 1044–1069, 2019.

Yoshimatsu, H. “Japan’s Export of Infrastructure Systems: Pursuing Twin Goals Through Developmental Means.” The Pacific Review 30 (4): 494–512, 2017.

Zhao, H. “China–Japan Compete for Infrastructure Investment in Southeast Asia: Geopolitical Rivalry or Healthy Competition?” Journal of Contemporary China 28 (118): 558–574, 2019.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, ODA ni Kansuru Ishiki Chosa (Opinion Poll on ODA [Available in Japanese only]), 2009.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/press/pr/chosa/yoron/chosa_oda.html

Sato Jin, The Making of Development Cooperation: Ecological History of Dependency and Self-Reliance, University of Tokyo Press, 2021.

Reconsidering the History of Japan's Development Cooperation Series, Vol. 7: The Making of Development Cooperation: Ecological History of Dependency and Self-Reliance - JICA Ogata Research Institute

Shinrai to Kaihatsu Kyoryoku Kenkyu-kai (Study Group on Trust and Development Cooperation), Shinrai to Kaihatsu Kyoryoku: Tasha to no Kankeisei wo Mirai ni Ikasu (Trust and Development Cooperation: Leveraging Relationships with Others for the Future [Available in Japanese only]), 2023.

https://www.jica.go.jp/jica_ri/publication/booksandreports/1529266_21881.html

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Indoneshia ni Taisuru Nihon no Kyoryoku no Sokuseki (The History of Japan’s Development Cooperation in Indonesia [Available in Japanese only]), 2018.

https://www.jica.go.jp/Resource/indonesia/office/others/ku57pq0000338if4-att/201804.pdf

Harashima Yohei, “Kaihatsu Enjo ni Okeru Kankyo Mondai he no Hairyo: JICA Kankyo Shakai Hairyo Gaidorain Kaitei no Jirei (Considering Environmental Issues When Providing Development Assistance: In the Case of the Revision of the JICA Guidelines for Environmental and Social Considerations [Available in Japanese only]),” Kankyo Kagakukai Shi (Journal of the Society of Environmental Science [Available in Japanese only]), 35 (4), pp. 181-188, 2022.

Yamada Junichi, Japan's Cooperation to Infrastructure Development: Its History, Philosophy, and Contribution, University of Tokyo Press, 2021.

Reconsidering the History of Japan's Development Cooperation Series, Volume 5: Japan's Cooperation to Infrastructure Development: Its History, Philosophy, and Contribution - JICA Ogata Research Institute

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed in this blog post are the author’s and do not reflect opinions of JICA or the JICA Ogata Research Institute.

Endo Kei

Endo is a Research Fellow at the JICA Ogata Research Institute since 2021. He joined JICA in 2010 and has worked at the South Asia Department (as an officer in charge of India), the Indonesia Office and the Operations Strategy Department there. Endo’s main research areas include infrastructure development and management, public-private partnerships (PPPs) and sustainable development.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

事業事前評価表(地球規模課題対応国際科学技術協力(SATREPS)).国際協力機構 地球環境部 . 防災第一チーム. 1.案件名.国 名: フィリピン共和国.

scroll