Overview

- Summary of Activities

- The goal of human security is to protect people from threats, such as poverty, conflicts, and disasters, so that each individual has the opportunity and choice to realize their potential and to be able to address threats on their own. To achieve this goal, JICA assists governments in developing countries in both sustainably protecting people from threats and acquiring the systems and capacity to provide administrative services that accurately meet people's needs. The agency also offers comprehensive cooperation by working to empower local communities and people so that they can solve problems independently and improve their lives on their own.

What is “human security”?

What kind of concept is “human security”?

Human Security Now, the final report by the 2023 Commission on Human Security (Note 1), co-chaired by Ogata Sadako (former JICA President) and Professor Amartya Sen (current Harvard University professor), defines human security as the protection of “the vital core of all human lives in ways that enhance human freedoms and human fulfilment.”

Today, protecting individual human security through security by the state alone is becoming increasingly difficult. Conflicts, global warming, the proliferation of weapons and drugs, and the spread of infectious diseases—these problems easily transcend the framework of a state and threaten the lives and livelihoods of people. Given these phenomena, the concept of human security is believed to be necessary to protect the dignity of each individual's life and livelihood. At the center of this concept is “people,” with an emphasis placed on the importance of people steadily gaining strength and self-reliance.

(Note 1) Commission on Human Security: In response to Japan's appeal at the United Nations Millennium Summit in 2000, the Commission was established in January 2001 with Ogata Sadako, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and Professor Amartya Sen, President of Trinity College, University of Cambridge, as co-chairs. The commission is independent from the United Nations and national governments, but its activities are conducted in close collaboration with UNHCR, the United Nations Development Program, the Rockefeller Foundation, and other organizations.

Background of the birth of human security

Although the number of interstate wars has decreased since the end of the Cold War, there is a high incidence of domestic and regional conflicts based on ethnic, religious, and cultural differences. There are countries and areas where the state is failing to perform its functions, or where minorities are oppressed by the ruling majority. In such cases, states may not be able to satisfactorily fulfill their role of protecting people’s lives and property, and many civilians fall victim to the resulting conflicts and internal turmoil. What is more, the advance of globalization has created the possibility for massive and instant flows of people, goods, services, money, and information, and economic activities and people are becoming increasingly interconnected across international borders. On the one hand, these transformations have brought prosperity to the international society, but on the other, they have spurred the expansion of transnational terrorism and crime, as well as the spread of infectious diseases. The effects of an economic crisis occurring in one country can thus easily extend across borders. At the same time, such changes have led to a worsening of global issues, including climate change and energy problems.

As a result, people are exposed to threats that cannot be dealt with solely within the state, and which cannot be solved through unilateral efforts alone. The perspective of human security emerged from such a context—one in which it is no longer relevant to consider the nation state alone as the unit for dealing with security issues—advocating the need to focus on the security not only of the state but of individuals.

Human security as part of Japan’s ODA policy

When renewing its ODA Charter in 2003, the Japanese government stressed the importance of incorporating the concept of human security within its assistance. Furthermore, the new Medium-Term Policy on ODA formulated in February 2005 stated that human security “means focusing on individual people and building societies in which everyone can live with dignity, by protecting and empowering individuals and communities that are exposed to actual or potential threats,” and positioned it as “a perspective [that] should be adopted broadly in development assistance.”

Details of the final report of the Commission on Human Security

The final report of the Commission on Human Security describes human security as complementing the concept of national security, expanding the scope of human rights, and promoting human development from the following four perspectives.

People-centered: its concern is the individual and the community rather than the state.

State security focuses on other states with aggressive or adversarial designs. States built powerful security structures to defend themselves—their boundaries, their institutions, their values, their numbers. Human security shifts from focusing on external aggression to protecting people from a range of menaces.

Menaces: menaces to people’s security include threats and conditions that have not always been classified as threats to state security.

State security has meant protecting territorial boundaries with—and from—uniformed troops. Human security also includes protection of citizens from environmental pollution, transnational terrorism, massive population movements, such infectious diseases as HIV/AIDS and long-term conditions of oppression and deprivation.

Actors: the range of actors is expanded beyond the state alone.

No longer are states the sole actors. Regional and international organizations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society are involved in managing security issues.

Empowerment: achieving human security includes not just protecting people but also empowering people to fend for themselves.

Securing people also entails empowering people and societies. In many situations, people can contribute directly to identifying and implementing solutions to the quagmire of insecurity.

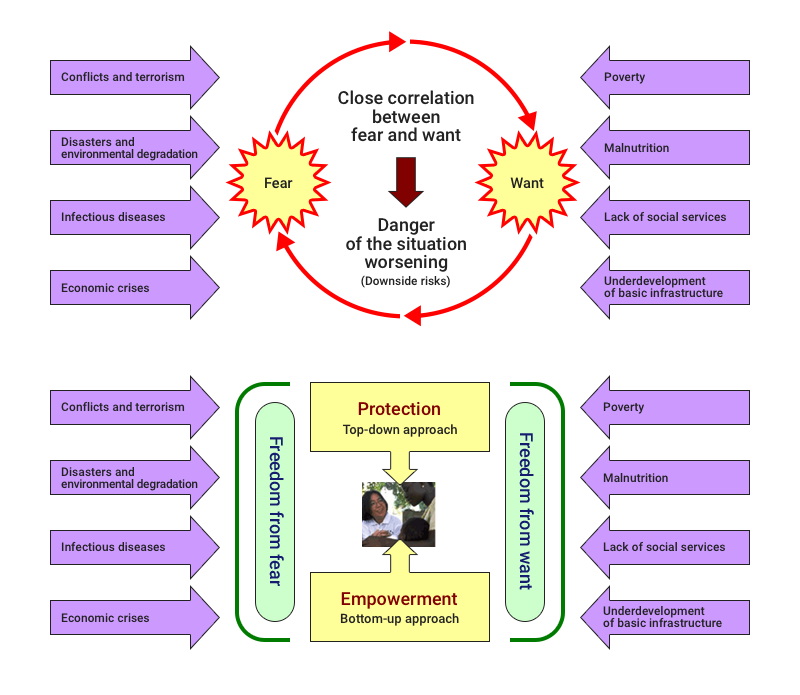

People are exposed to diverse threats that fall under the categories of “fear” and “want.” “Fear” includes conflicts and terrorism, disasters and environmental degradation, the spread of infectious diseases, and economic crises. “Want” includes poverty, malnutrition, lack of social services such as education and health care, and the underdevelopment of basic infrastructure. These categories are also interrelated, and people are at risk of having their situations further exacerbated by the overlapping of threats (downside risks). Human security refers to the creation of a situation in which people have freedom from “fear” and “want,” and can survive with peace of mind and live with dignity.

In light of the above, the concept of human security can be simply described as a framework for creating a society in which people can live in peace and security.

Human security in the development field: threats to people and their correlations

The history surrounding human security

| 1994 | Featured in the “Human Development Report 1994” (UNDP), garnering worldwide attention. |

|---|---|

| 1998 | Mentioned by the then Prime Minister of Japan Obuchi Keizo in a speech in Singapore. |

| 1999 | Establishment of the United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security. Inauguration of the Human Security Network. |

| 2000 | The then Prime Minister Mori Yoshinori of Japan called for the establishment of the Commission for Human Security (UN Millennium Summit). |

| 2001 | Establishment of the Commission on Human Security. |

| 2003 | The Commission on Human Security submitted a final report to the UN Secretary-General. Mentioned in declarations and summary documents of the Evian Summit, TICAD III, APEC, etc. |

| 2005 | The 2005 World Summit Outcome adopted by the United Nations General Assembly mentioned the assembly’s commitment to further discussing the concept of human security. |

| 2006 onwards | “Friends of Human Security” meetings held—(1) October 2006, (2) April 2007, (3) November 2007, (4) May 2008. |

| 2007 | Senior Official-Level Meeting on Human Security held. |

| 2008 | UN General Assembly Thematic Debate on Human Security. Mentioned in the TICAD IV “Yokohama Declaration.” |

Introduction of human security by JICA

After its rebirth as a “new JICA” in 2008, the agency unveiled a new vision of “Inclusive and Dynamic Development” and put forth four missions to achieve this.

One of the four missions that JICA has set for itself as an organization is “to achieve human security.” JICA has positioned this as one of its most important missions because it recognizes the following three issues.

First, given the past half-century history of ODA, there is now a need for a renewed emphasis on “people-centered assistance.” To date, international cooperation, including ODA, has been devised in various ways to better serve the diverse requirements of developing countries. As a result, the concentration and division of labor has advanced significantly, and assistance has tended to be fragmented by sector, such as education, health, and agriculture, or based on forms of assistance, such as technical cooperation, grant aid, and loan assistance. However, the issues surrounding people are diverse and also intricately intertwined with each other. To respond to that reality and appropriately address the issues that people are facing, it has become indispensable to accurately identify and comprehensively tackle these complex problems.

Second, with the collapse of the Cold War structure, comprehensive approaches to development and peace have become increasingly necessary. Many people in developing countries who are living in poverty are at the same time being directly or indirectly affected by armed conflicts, which put their lives, livelihoods, and dignity in jeopardy. It is also a fact that poverty and social disparities in developing countries serve as factors of conflict.

Third, JICA recognizes the need to intensify its efforts to support “countries and regions facing more difficult conditions.” In the past, there was an argument that it would be better to provide support to countries and regions where it is expected to be more effective. However, a common understanding is taking shape worldwide that peace and development of the overall international community will not be possible without aid agencies working to ameliorate the problems encountered by the people of “countries and regions facing more difficult conditions.”

JICA’s practice of human security

The human security perspective is always ingrained within the execution of JICA’s projects. The agency views the practice of human security not as a uniform approach, but rather as one that requires a detailed response to the diverse circumstances of the people of each country and region.

There have been many JICA projects that have incorporated these perspectives into their activities to date. However, going forward, the agency will review the content of its past projects once again and aim for cooperation that will reach more people and have a greater impact (ripple effect).

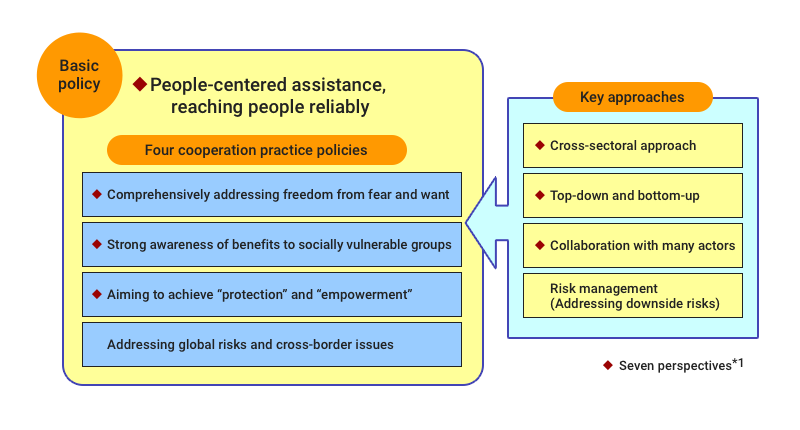

In order to put human security into practice, JICA aims to implement cooperation programs based on the basic policy of pursuing people-centered assistance and assistance that will reliably reach people. For this reason, JICA reviewed and reorganized its seven perspectives on human security and formulated four cooperation practice policies and four key approaches.

Four cooperation practice policies and four key approaches

Basic policy

Implementing people-centered assistance and reaching people reliably.

Four cooperation practice policies

Cooperation that comprehensively addresses freedom from fear and want

As mentioned above, people are threatened by diverse menaces related to “fear” and “want.” “Fear” can be induced by conflicts, terrorism, crime, disasters, environmental degradation, the spread of infectious diseases, and economic crises, among other factors, and “want” by poverty, malnutrition, lack of social services such as education and health care, and the underdevelopment of basic infrastructure, etc.

These various threats are closely correlated, with “want” generating and increasing “fear,” which in turn generates more serious “want.” Cooperation based on the human security approach involves considering both fear and want, and comprehensively dealing with the problems people are confronted with.

Strong awareness of the benefits to socially vulnerable groups

JICA maintains a focus on socially vulnerable groups—those whose lives, livelihoods, and dignity are or are likely to be at risk. It conducts detailed cooperation to ensure that its benefits reach the most vulnerable members of society, who can be said to include people living in poverty, those with disabilities, indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, the elderly, women, children, refugees, returnees, people living in remote areas, and other diverse populations. JICA believes that ensuring that the benefits of cooperation reliably reach people who have been left behind by conventional development and progress will contribute to the stability of the global community.

Aiming to achieve “protection” and “empowerment”

JICA aims to improve the capacity of both central and local governments, as well as local communities and people, and to build desirable relationships between them.

The agency has implemented a number of assistance programs aimed at helping governments in developing countries strengthen their ability to protect their people from threats in a sustainable manner. By enhancing the coordination functions and policies of central governments and improving the human resource development and administrative capacity of local governments, JICA is helping these governments protect people from threats and deliver administrative services that accurately meet people's requirements. Meanwhile, there have not been many cases where community empowerment has been implemented via major JICA projects. However, in cases where the capacity of government agencies is very limited, it is necessary to consider more flexible support for the broader development of communities and the empowerment of people, rather than assume that the capacity for protection is held by the government alone. JICA provides assistance not only to people as financial aid, but also in the form of support for the empowerment of local communities and people so that they can solve their problems independently and improve their lives on their own. The agency also believes that empowering people to act on their own behalf will foster the ability of communities and people to appeal to their governments and administrations.

Addressing global risks and cross-border issues

Some of the issues surrounding people are threats that cannot be addressed by single states, such as infectious diseases and international crime, which extend beyond national borders, and global-scale issues such as climate change and energy problems. It is the vulnerable areas and socially vulnerable groups that are most affected by such threats, which, by accelerating societal vulnerability, risk further plunging impoverished people into deprivation and activating a host of latent problems that can exacerbate their situation (downside risks).

| Examples of global risks | Examples of JICA's fields of cooperation | |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-border threats | International crime | Maritime security, customs risk reduction, anti-drugs measures, countermeasures against trafficking in persons, etc. |

| Spread of infectious diseases due to movement of people and animals | Countermeasures against HIV/AIDS, avian influenza, SARS, etc. | |

| Financial and economic crises | Strengthening and stabilizing financial systems | |

| Global-scale issues | Global environmental issues | Empowerment of Clean Development Mechanism-related institutions, strengthening of observation systems, conservation of the natural environment, etc. |

| Population, food, and energy issues | Food security (increasing food production, food diversification, etc.) | |

| Energy conservation, renewable energy, etc. | ||

| Disasters | Emergency assistance for disasters, disaster risk reduction, etc. | |

| Spread of infectious diseases caused by rising temperatures | Malaria prevention, etc. | |

Four key approaches

(1) Multi-sector approach

When reviewing people's issues from the perspective of safety in their daily lives, we see that many issues are inextricably intertwined. Using a sector-specific approach is often not enough to tackle that intricately complex group of issues. Focusing on the issues faced by people, and combining diverse expertise to resolve these issues in a cross-sectoral manner, requires a combination of diverse forms of cooperation within individual sectors and a comprehensive approach to development issues across sectors.

(2) Top-down and bottom-up approaches

For governments to acquire the capacity to protect people from threats, central government coordination functions and policies must be enhanced, and local-government human-resource-development and administrative capacities must be improved. Furthermore, to prevent the results of JICA's assistance from being temporary and limited, and to allow for them to be disseminated to and institutionalized within other regions, the strengthening of government capabilities is also indispensable. On the other hand, the expected role of the government differs from country to country. JICA has also experienced many cases in which, after the conclusion of a cooperation project, the counterpart government agencies were expected to independently develop the results of the cooperation, but things did not work out as expected and the results were not sustained. Hence, going forward, given the possibility of increased assistance to countries with weakened government structures, such as post-conflict countries, it is important to broaden efforts to reach out directly to communities and people in order to empower them to solve problems and improve their lives on their own, and to avoid the major risks in front of them. JICA believes that combining assistance at both the governmental level and the community/people level in this way will ensure that assistance reaches the people and that the results of the cooperation will be sustainable.

(3) Collaboration with diverse actors

Human security is achieved by everyone striving to respond to the difficult conditions and threats that people face from a “people-centered” perspective. Also, in order to protect people from diverse threats, a more detailed and comprehensive approach is needed, including a multi-sectoral approach and a combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches, as mentioned above. This is why JICA aims to bring together diverse actors in developing countries, including international organizations, governments and government-related agencies, community organizations, businesses, external consultants, NGOs, and resident organizations, in order to achieve project development that is impactful overall.

(4) Risk management (response to downside risks)

In the real world of developing countries, diverse external shocks such as conflicts, economic shocks, and natural disasters may further deteriorate the situations in which people and countries find themselves (downside risks). Even if cooperation projects in developing countries have been successful, once a major crisis (e.g., conflict, disaster, or widespread infectious disease) occurs, the accumulated achievements might be lost. In human security, it is essential to consider how to respond to sudden threats, the danger of deteriorating circumstances, and the possibility of downward spiraling processes. For example, in the case of providing assistance to a country that is hit by cyclones every year, it is necessary to incorporate into cooperation projects innovations and considerations to reduce downside risks, such as adding a disaster risk reduction perspective to agricultural development.

JICA’s framework for incorporating human security

*1 Based on the fact that human security was reflected in the Medium-Term Policy on ODA in 2005, the concept was included as one of the three pillars of reform in the “First Phase of JICA’s Reform Plan.” Then, to promote the practice of human security, the following seven perspectives were introduced.

- 1 . People-centered assistance, reaching people (not the country) reliably.

- 2 . Assistance that sees the people of developing countries not only as the object of assistance (protection) but also as the future actors of development and emphasizes empowerment of the people for this reason.

- 3 . Assistance that is genuinely helpful to those who are socially vulnerable, whose lives and livelihoods and human dignity are at stake, or are highly likely to be at stake.

- 4 . Assistance that aims for both “freedom from want” (helping people escape poverty) and “freedom from fear” (helping people escape the threat and shock of conflicts, disasters, etc.).

- 5 . Assistance that focuses on people's problems, analyzes the structure of these problems, and then combines diverse expertise to comprehensively address them (cross-sectoral approach).

- 6 . Assistance that approaches both the government (central and local) and the local community/people in developing countries to contribute to the sustainable development of these countries or local communities.

- 7 . Assistance that aims to achieve a greater impact through collaboration with diverse organizations and people (donors, external consultants, NGOs, etc.) in developing countries.

scroll